If we’ve exited the Quiverfull Movement, we know quite a bit about the Optimism Bias and it’s many faces. I used wishful thinking to cope with life, attributing positive qualities to everyone but myself. It’s not so bad if what you’re contending with proves to be positive, but that blessing usually doesn’t extend to the rank and file member of a group. I still contend with the negativity that I learned, often achieving it by idealizing someone else at my own expense.

When someone exits a high demand group, they bring much baggage with them. Shame and self-deprecation which are used to keep members in line erode confidence over time. When a person’s honeymoon phase of membership ends, the punishment of infractions that they didn’t know existed begins. The hidden curriculum can’t convey everything, and so much of the unpleasant aspects of a group go undocumented. Gradually over time, punishments including small, trivial ones erode confidence and change the way a person feels about themselves, usually without their notice. Compliance with the dysfunctional view of self becomes the ‘new normal,’ and it creates a cascade of self-generated, pleasurable, addictive neurohormones which reward conformity.

All of that changes instantly when a member falls out of favor. The brain sucks up all of the happy juice that it learned to make, and instead, punishment and pain suddenly make feeling good a distant memory. Is it any mystery that people emerge from such experiences with gloomy, pervasive negativity about their lives and themselves?

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and complex trauma taint human perspective with a negative bias as a survival mechanism, something that keeps us alive and functional, but we can get stuck in it if we were not able to survive the trauma very well. Mark Twain once said that a cat who jumps up on a hot cook stove only to suffer burned feet will likely never attempt to do it again. I like to think of Thomas Edison as an enigma of contrast. He made 10,000 failed attempts to create a working light bulb, but he attributed the failures as necessary prerequisite steps in the process. Most people who leave a high demand group and indeed come to terms with their experience don’t possess enough hope for such an undertaking. If they do, they’re likely jumping back into the bias of magical thinking as an ineffective way of coping with their disappointment.

The Irresistible Negative

We human beings already prefer negative information, remembering the things in life that we find novel. We neglect the white tablecloth to pay attention to the wine stain. We hold on to criticism and remember it far better than we do praise. We identify signs of anger in another person’s facial expression far more rapidly than we do any other emotion. The brain also converts emotionally negative experience into long term memory more effectively. Whether or not we carry some innate, vestigial sensitivity to perceived threat, we know that human beings pay more attention to negatives than they do positives.

This also plays into cultic gloom and doom themes. Media bombards us with tragedies that make for far better news headlines than do the prosaic elements of our lives. In times past before we had a worldwide network that relays information across the globe instantaneously, it took months if not years for most people to learn about a tragic situation on the other side of the world. Better access about danger and tragedy trick us into misinterpreting such occurrences as a rise in them, an attribution error that cults exploit to keep their followers entrenched.

Negativity and Agency

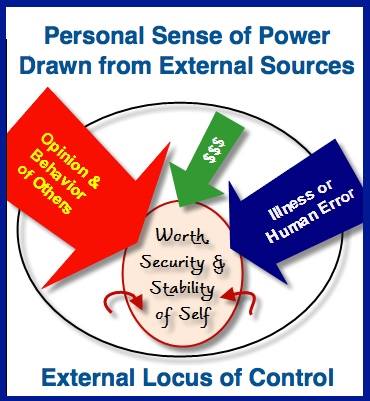

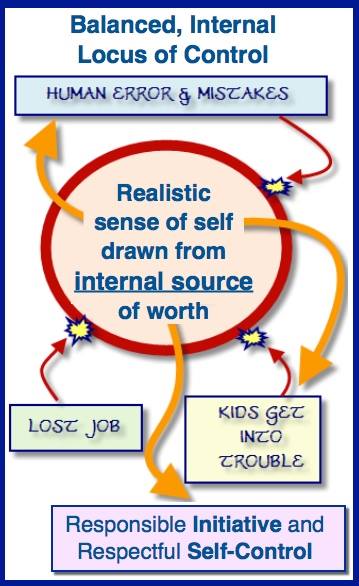

Rather than seeing oneself as a capable, reasonable person with control over a good many things which can be managed wisely, members become victims of circumstance over time. Negativity changes the sense of their own agency into an assumed dependency – a means of coping and survival within such a group. Apprehending a healthy sense of agency takes time. Good cognitive-behavioral work to stop automatic negative thoughts (ANTs) from taking over might be the most powerful way of thinking about negativity. Journaling daily can shine a powerful light of insight on the automatic thought-stopping ideas and cliches which people learn while members of a high demand group.

Peace and joy seem like distant memories for a time, especially for the first few months after exiting. An exit counselor that I know advises keeping expectations for recovery in check, for most people need a year or two to process their cult experience. Alcoholics are told to give themselves a grace period, allowing themselves one month for each year that they were addicted. I think that’s an excellent starting point for understanding recovery from a religious group as well. Using a journal to keep track of time and scrutinize one’s own thoughts can also be used to track positive experiences and signs of growth.

In time, we learn how to assess situations more accurately so that we might build better expectations. This more realistic view of life informs personal risk and thus facilitates healthier personal boundaries. We can discipline ourselves to pay equal attention to the good factors in our lives instead of giving into the elusive and often nebulous feeling that causes us to feel like hapless and helpless pawns.

Instead of succumbing to the isolation that trauma creates, staying connected with safe people who give us honest feedback also helps us to mitigate this bias. Talking with others who left a similar situation are perhaps the best source of validation and encouragement. We can then begin the harder work of ‘taking our power back’ as we build a new and realistic sense of control. Idealogical systems never made us impervious to trouble, but we need to reaffirm that we have a good deal of power over what we think which guides how we feel. With reflection and greater self-awareness, we learn to renegotiate who we are in the world and how we best fit into it without the gloom.

Further Reading:

- Gilovich, Griffin, and Kahneman’s Heuristics and Biases

- Banaji and Greenwald’s Blind Spot: Hidden Biases of Good People

- Ross’ Everyday Bias

- Braiker’s Whose Pulling Your Strings?

- One of the affordable books on Cognitive Bias at Amazon.com

Cindy is a nurse who was raised in Word of Faith, a Second Generation Adult of cultic Christianity. She and her husband dabbled in Calvinism and Theonomy as a foil to Christian anti-intellectualism, and they were exit counseled together when the walked away from a church that embraced Gothard’s teachings. Cindy escaped many Quiverfull pitfalls but became a social pariah for failing to birth a family. She’s been decrying the abuses of the Patriarchy Movement since 2004, and she writes about spiritual abuse at her blog, Under Much Grace. Read more about her here.

Stay in touch! Like No Longer Quivering on Facebook:

If this is your first time visiting NLQ please read our Welcome page and our Comment Policy! Commenting here means you agree to abide by our policies.

Copyright notice: If you use any content from NLQ, including any of our research or Quoting Quiverfull quotes, please give us credit and a link back to this site. All original content is owned by No Longer Quivering and Patheos.com

Read our hate mail at Jerks 4 Jesus

Check out today’s NLQ News at NLQ Newspaper

Contact NLQ at [email protected]