Quantum Theory, God, and Carl Peterson

Quantum Theology SR 5022

Quantum theory and God? Any connection? Should we construct a quantum theology? (O’Murchu, 2021)?

Hybrid physicist and theologian, the late John Polkinghorne, would certainly answer in the affirmative: we need quantum theology. “”Questions of causality ultimately demand metaphysical answering” (Polkinghorne, 2006, p. 139). However, such “metaphysical answering” might not be simple. Why? Because Niels Bohr’s Copenhagen version of quantum theory is indeterminist, while David Bohm’s holistic version is determinist. What’s a theologian to do?

Let me elaborate slightly. Copenhagen indeterminism is observational, not ontological. Bohmian determinism provides an ontology, a comprehensive worldview. Still, we ask, what is a theologian to do about these competing models of quantum mechanics?

Hybrid physicist and theologian Robert John Russell proposes a theological “answering” with his principle of NIODA (Non-Interventionist Objective Divine Action). Russell’s quantum theology is based on Copenhagen indeterminism. Still, we ask: might Bohm’s metaphysical answer and Russell’s theological answer be compatible? We’ll ask physicist Carl Peterson.

Science and Religion is the field within which we will be pursuing public theology here in this post. Nothing is more public than the physical world. And nothing is more public than the scientists who unlock its secrets. The mysteries within the atom astonish physicist and theologian alike. Might there be theological implications here? You betcha!

Copenhagen Indeterminism versus Bohmian Determinism

In this Patheos post, I’d like to turn to a controversy you’re not likely to learn much about on social media or even Patheos. It’s the debate among physicists over the interpretation of Quantum Mechanics (QM for short). What happens within the atom at the quantum level? Do those fast moving electrons and photons obey deterministic laws? Or not?

Why is this important? Because exploring sub-atomic physics brings us as close to fundamental to reality as we can get. That’s why. And, mystery of all mysteries, micro-reality seems to be indeterministic. That is, it seems to be. Maybe there’s a determinism that is hidden. Mmmmm? Might this affect quantum theology?

Why is this important? Because exploring sub-atomic physics brings us as close to fundamental to reality as we can get. That’s why. And, mystery of all mysteries, micro-reality seems to be indeterministic. That is, it seems to be. Maybe there’s a determinism that is hidden. Mmmmm? Might this affect quantum theology?

So, dear reader, I recommend you bracket out for a few moments any preset views you hold about supernaturalism, miracles, and anti-religious venom. Simply listen in on a controversy within science that could have implications for quantum theology. We will ask as John Horgan in Scientific American asks, “What does God, Quantum Mechanics, and Consciousness Have in Common?” Our proposed answers will look quite different, let me warn you.

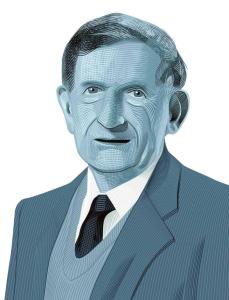

Meet Carl Peterson

Carl Peterson (Ph.D. Ohio University) is a physicist working both in academia and private industry. He taught physics and chemistry at Ohio Wesleyan University and Columbus State University. He has published on the electronic structure of polyatomic molecules. Today, as an independent scholar, he seeks to break the hegemony of the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics and advocates instead for David Bohm’s ontological interpretation in quantum theory.

Carl Peterson is not a quantum theologian. Yet, what he says about physics should make a quantum theologian sit up and take notice.

Setting the Quantum Theology Agenda: Robert John Russell’s QM-NIODA Theory

Our atheist friends keep whining that there is no such thing as a supernatural realm (Atkins, 2006). This means, there is no such thing as a miracle. And, if there are no miracles, then religion is bunk. Curiously, atheists can be just as superstitious as the religious believers they renounce. But, that’s another topic.

What is our present topic? Here it is: how does God work in the natural realm without supernatural intervention? The problem with atheists talking about supernaturalism is that they leap and scream like cheer leaders for naturalism. But, theologians are quite happy with studying how God works within the natural world in ordinary ways. So, by staring at the cheer leaders, our atheist friends have not noticed the actual game being played.

When we turn to the actual game being played, we see questions that require both scientists and theologians to address. Here is such a question that arises within the field of Science and Religion: how can God act in the natural world providentially yet not supernaturally or miraculously? At the quantum level within the atom, does God act in such a way that we experience it at the level of our human experience?

This is the kind of question asked by my friend and colleague, Robert John Russell. Bob is founder and director of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, California. Bob thinks he finds an answer in the indeterministic interpretation of QM.

“When we shift to an indeterministic world, a new possibility opens up. One can now speak of objective acts of God that do not require God’s miraculous intervention but offer, instead, an account of objective divine action that is completely consistent with science.” (Russell, 2008, p. 128).

Relying on indeterminism at the microlevel, Bob advances his QM-NIODA theory: Quantum Mechanical Non-Interventionist Objective Divine Action. “If God acts together with nature to produce the events of objective divine action, God is not acting as a natural, efficient cause” (Russell, 2008, p. 128). Or, “Essentially what science describes without reference to God is precisely what God, working invisibly in, with, and through the processes of nature, is accomplishing” (Russell, 2008, p. 214).

In what follows, I’d like to put Bob’s theological interpretation of QM to the test. How? By interviewing physicist Carl Peterson. Carl, as you will see, will not grant the indeterminist interpretation of QM put forth by Niels Bohr and the Copenhagen school. What might this mean for Bob’s NIODA theory (Russell, The Physics of David Bohm and Its Relevance to Philosophy and Theology, 1985)?

Quantum Mechanics and God Again? An Interview with Carl Peterson

TP.1. For decades now, the indeterminist interpretation of QM has reigned as dominant. Why then, Carl, do you assert that Niels Bohr’s indeterminist interpretation is mistaken and David Bohm’s deterministic hidden variables interpretation is more adequate?

CP.1. I don’t believe the indeterminist interpretation at Copenhagen is mistaken. It’s just inadequate. Or, better, Bohm’s ontological interpretation is more adequate.

But first, a little bit of history about Bohm’s interpretation! In February of 1951, Bohm published an advanced book that he entitled Quantum Theory (Bohm D. , Quantum Theory, 1951). This book has twenty-three chapters. When one reads the last two chapters, it seems that Bohm accepted Bohr’s response to Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen’s (EPR) criticisms of quantum mechanics not being complete, in favor of Bohr’s indeterminist interpretation.

However, after publishing the book, and discussing it and the EPR criticism about quantum mechanics with Albert Einstein, Bohm started rethinking some of his concepts and statements in the book. Primarily, about hidden variables and the, well known, underlying concerns with the Copenhagen interpretation and its measurement problem. Bohm’s first two papers setting forth his renewed thoughts on those subjects were received by Physical Review on July 5, 1951. This was four months after the publication of his book. Bohm entitled his papers: “A suggested Interpretation of the Quantum Theory in Terms of “Hidden” Variables I & II,” 1952). In his acknowledgment he thanked Dr. Einstein for several interesting and stimulating discussions.

Now to Bohm’s Hidden Variables interpretation! Bohm put the wavefunction in the form normally used to have the Schrödinger equation (SE) reduced to classical mechanics. Next he inserted it into the Schrödinger equation (Bohm called the SE the mathematical apparatus). And then, by separating the real and imaginary parts he obtained two equations of motion, one for R, and one for S. However, Bohm did not proceed directly to the classical limit, as is usually done, by setting the quantum of action, h = 0, in the equation of motion for S since h never equals 0. He theorized there might be more microstructure associated with the quantum field than had previously been determined or realized by retaining the quantum of action (That was his visionary move).

The questions arising on suggesting more microstructure became, by producing two equations of motion, that are rigorously equivalent to the SE. What is their physical interpretation? Does the microstructure add to the underlying independent reality of the wavefunction? Does its ontology still lead to agreement with experimental observations? Keep in mind there is no ontology associated with the Copenhagen interpretation. So, Bohm went to work on answering these questions!

Quantum Questions Demand Metaphysical Answers

TP. Interjection. Recall what Polkinghorne said in the citation above: “Questions of causality ultimately demand metaphysical answering”(Polkinghorne, 2006, p. 139). Bohm’s ontology of QM provides such an answer. This ontological interpretation attracts Carl Peterson. TP

CP. Bohm reinterpreted the wavefunction as representing a fundamentally real field described by its amplitude function, R, and its phase function, S. Moreover, there are real particles. And, every real particle is never separated from its quantum field with a well-defined position that varies continuously and is causally determined. Bohm found that the average momentum is related to the phase function. And highly important, Bohm noted every particle in the equation of motion for S contained a classical potential, V, plus an additional term with the quantum of action. Bohm theorized the term could be considered an additional potential, which he called the quantum potential.

Furthermore, the quantum potential is the microstructure which introduces new concepts not considered or even accepted as essential in the structure of classical physics. Let’s name a few: a), the quantum potential depends only on the mathematical form of its wavefunction, and not on the intensity of the quantum field. This is different from, for instance, the Newtonian gravitational potential, which tends to decrease with increasing distance apart. b), The reaction of each individual particle may depend nonlocally on the configuration of the other particles regardless of distance, where the particle position and momenta are hidden variables. c), active information, different from the usual understanding in classical physics as a quantitative measure in communication but understood by Bohm’s interpretation as a feature of the quantum potential, in which very little energy directs or uses a much greater energy, he gives examples in many of his works, such as radio waves and the DNA molecule, d). Wholeness, whereby every region of space is connected by the quantum potential into an unbroken wholeness or unifying whole. Bohm discusses all these concepts in his book with B. J. Hiley, The Undivided Universe (Bohm D. a., 1994).

Furthermore, the quantum potential is the microstructure which introduces new concepts not considered or even accepted as essential in the structure of classical physics. Let’s name a few: a), the quantum potential depends only on the mathematical form of its wavefunction, and not on the intensity of the quantum field. This is different from, for instance, the Newtonian gravitational potential, which tends to decrease with increasing distance apart. b), The reaction of each individual particle may depend nonlocally on the configuration of the other particles regardless of distance, where the particle position and momenta are hidden variables. c), active information, different from the usual understanding in classical physics as a quantitative measure in communication but understood by Bohm’s interpretation as a feature of the quantum potential, in which very little energy directs or uses a much greater energy, he gives examples in many of his works, such as radio waves and the DNA molecule, d). Wholeness, whereby every region of space is connected by the quantum potential into an unbroken wholeness or unifying whole. Bohm discusses all these concepts in his book with B. J. Hiley, The Undivided Universe (Bohm D. a., 1994).

The mathematical apparatus still provides the necessary values for observed quantities just as the Copenhagen interpretation does. But it also provides for particles and trajectories in a completely deterministic system. That is, the initial position of a particle uniquely determines its future behavior. And in the words of the late James T. Cushing, which I have memorized, “Here we have a logically consistent and empirically adequate deterministic theory of quantum phenomena.” And I might add, what’s the problem; why don’t we use it?

TP. 2. Physicist David Bohm is a cosmic holist. Here is what Bohm says. “I propose a view that I have called unbroken wholeness. Relativity and quantum physics agree in suggesting unbroken wholeness, although they disagree on everything else. That is, relativity requires strict continuity, strict determinism, and strict locality, while quantum mechanics requires just the opposite—discontinuity, indeterminism, and nonlocality….They both agree, however, on the unbroken wholeness of the universe.” (Bohm, 1988, p. 65). What does this mean?

CP.2. You ask: what does this quote from Bohm mean? I really like Bohm’s personification of his proposed view on the concept of unbroken wholeness (Bohm D. , Wholeness and the Implicate Order, 1980) for interpreting two significant, as well as necessary, discoveries of twentieth century physics: Relativity Theory and Quantum Theory. These two discoveries led to continued advancement in physics and the search for understanding the reality of the physical world, when many physicists believed there was nothing else to be accomplished in their discipline.

Let me state this question another way. What does it mean that Relativity Theory and Quantum Theory are not consistent mathematically, but display an unbroken wholeness in their concepts?

Bohm was seeking some way forward where the mathematical apparatus would apply to both theories without contradictions in their concepts. What Bohm found was that relativity theory and quantum theory have the quality of unbroken wholeness in common, although it is achieved in a different way, but theorized it may be a way forward.

First, let’s consider how wholeness is achieved in relativity theory. Simply put, the basic idea is that a point in spacetime is called an event, which is totally distinct from all other point events. So, all structures may be seen as configurations in a universal field, which is a function of all the space-time points. Therefore, the field is continuous and inseparable. A particle (physical object) in the field has to be treated as a singularity or stable pulse of finite extent. The field around the stable pulse lessens in intensity with increasing distance from it, but it does not shrink to zero. As a result, all the fields for the stable pulses merge to form a single structure, of unbroken wholeness. A singularity in space-time is non-mechanistic construct, which is independent of the Cartesian grid system.

Next, consider how wholeness is exhibited in Bohm’s interpretation of quantum theory. It is achieved through active information listed as a concept represented by the quantum potential. The quantum potential is the microstructure for transmitting influences on distance parts of the correlated quantum system through nonlocal connections. It basically interconnects all distant objects of the quantum field into a single system, and as Bohm states, with an objective quality of unbroken wholeness.

In physics, all fields are defined by space-time points put in order and understood using the Cartesian co-ordinate grid. And, if necessary, they are extended to curvilinear coordinates. But it is a mechanistic order, whose parts have and independent existence in different regions of space and time. So, it has been and continues to be inadequate for ordering the unbroken wholeness and contradictions of quantum theory and relativity theory. Such a situation calls for seeking a different order that will allow both theories to be consistent conceptually, and potentially pave the way for further advancements to these theories. Bohm has suggested the Implicate Order, but this would be a discussion for another interview or paper.

TP.3. Modern science is objective. It expunges your and my consciousness. David Bohm complains. He says, “A postmodern science should not separate matter and consciousness and should therefore not separate facts, meaning, and value.” (Bohm, 1988, p. 61). Carl, how do you think a scientist should include consciousness?

TP.3. Modern science is objective. It expunges your and my consciousness. David Bohm complains. He says, “A postmodern science should not separate matter and consciousness and should therefore not separate facts, meaning, and value.” (Bohm, 1988, p. 61). Carl, how do you think a scientist should include consciousness?

CP.3. How do I, Carl Peterson, think a scientist should include consciousness? First let me emphasize: I am a Bohmian, no doubt. And work by Bohm on “An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum Theory” (Bohm D. a., 1994) has shown there is a consistent and empirically adequate deterministic theory available.

In that regard, it would be fruitless to try to account for consciousness within the Cartesian coordinate grid system. In fact, any research in which the Cartesian coordinate grid system is used would not cohere with consciousness. Why? Because it is mechanistic.

However, paradoxically, it takes a conscious mind to be aware, to think, and do critical work in physics. This becomes clearer in quantum theory. Even so, consciousness doesn’t appear in the equations.

Again, being a Bohmian I will follow his lead. It is Bohm’s proposal that the implicate order is where quantum theory and consciousness become compatible. And I agree with his proposal.

What is the implicate order you ask? My answer is: implicate order theory takes what quantum theory and relativity theory have in common, wholeness, and works naturally with their contradictions, which come from using the Cartesian grid, through the mental, physical and sensory awareness that embraces consciousness.

The theory is limited! No physical theory gives a perfect replica of reality, since a theory is part of the thought process. And the thought process is limited by information humans receive and their memory for retention of that information.

TP. 4. Now, Carl, let me stir up some trouble. I know you are a physicist. But, I’d like you to speculate about theology.

For decades now, some theologians have relied on the indeterminist interpretation of quantum mechanics to account for God’s non-miraculous action in nature’s world. Let me quote again Robert John Russell: “When we shift to an indeterministic world, a new possibility opens up. One can now speak of objective acts of God that do not require God’s miraculous intervention but offer, instead, an account of objective divine action that is completely consistent with science.” (Russell, Cosmology from Alpha to Omega, 2008, 128). How might this change if we were to adopt the Bohmian rather than the Copenhagen interpretation?

CP.4. You ask me about QM-NIODA. How might it change if the Bohmian interpretation was adopted rather than the Copenhagen interpretation?

Let me state emphatically that Bohmian determinism is compatible with QM-NIODA ontological indeterminism, and the measurement problem doesn’t exist with Bohm’s interpretation. And, the quantum potential presents new concepts that have to be considered since they don’t exist in the Copenhagen interpretation.

So, it seems to me that changes would come about because much of the activity that occurs in the microworld happens because of the quantum potential in Bohm’s interpretation. But Russell labels these “thorny issues.” Setting that statement aside, there are two types of changes that seem necessary to locate the physics for NIODA to cohere with the Bohmian interpretation. Number one leads to number two. I briefly discussed some features of number two earlier. The two types are:

1) new developments in physics always require attention to language. This is necessary to communicate the perception and thinking about the new development. Therefore, language would be the first type of change in NIODA.

2) different factors underlie the different language. Specifically, Russell’s NIODA needs to account for quantum potential as Bohmn articualtes it. Bohm’s visionary insight of recognizing the quantum potential, since activity is taking place in the quantum world because of it. Therefore, the features brought in by the quantum potential are most important as well with the different language. I mentioned four earlier. I see those as most crucial. Let’s set the stage!

The mathematical form of the wavefunction sets the quantum field. And then, nonlocality locates Divine Action in the quantum world, since it is completely the product of the quantum potential. Recall from earlier question that the quantum potential doesn’t exist in the classical limit, therefore nonlocality doesn’t exist there either. Enter active information, which is produced in the quantum field, allowing influences on remote parts of the quantum system to respond in a correlated manner. Moreover, the quantum potential interconnects every region of space and imparts a quality of inseparable wholeness. In other words, the wavefunction for the quantum system determines the nonlocal connections on its distant parts.

TP.5. Carl, you get the last word. Anything else you might wish to say?

A Robert John Russell Clarification

Conclusion

Do Patheos bloggers take up quantum theology? Sometimes.

But, not every Patheos blogger is happy with quantum theology. Especially Will Duquette. Duquette modestly formulates his own laws. Here’s one that’s relevant: Every application of quantum mechanics to philosophy or religion is absurd. Absurd? Why? Duquette says that a theologian is too ignorant to rightly weigh the import of physics. He contends, further, that a physicist is too smart to dabble in theology. What about a hybrid physicist-theologian such as Ian Barbour, John Polkinghorne or Robert John Russell? Duquette says, contrary to the testimony we’ve just assembled: if “the speaker is both a quantum physicist and a philosopher/theologian…he’ll be too wise to apply quantum mechanics to philosophy or theology.” This makes Duquette’s reasoning more absurd than his law.

Here in this discussion of Science and Religion, we are asking about divine action in nature’s world. The systematic theologian is the obligated to construct a reasonable and intelligible worldview that explains God’s providential yet non-interventionist action. Quantum theory entices the theologian like a yummy ice cream cone on a hot sunny day.

But, one step at a time. Before the quantum theologian can deal directly with divine action in nature’s world, the question of the relationship between objective fact and subjective consciousness must be resolved. Henry Stapp, physicist at the University of California at Berkeley, has worked on this question for decades.

“Quantum mechanics…assigns to mental reality a function not performed by the physical properties, namely, the property of providing an avenue for our human values to enter into the evolution of psycho-physical reality, and hence make our lives meaningful” (Stapp, 2017).

What we see most forcefully in the quantum ontology of David Bohm is a grounding for both consciousness and what consciousness knows in a single holomovement. This QM ontology attracts Carl Peterson.

This should attract Robert John Russell as well. Bohm’s notion of undivided wholeness in a single holomovement provides an inclusive ontology that coheres with quantum theory and adds a level of wholeness to Russell’s theory of divine action.

In conclusion, Robert John Russell need not choose between the indeterminism of Copenhagen and the determinism of Bohm. His quantum theology could benefit from both.

Click on the Patheos Science and Religion Resource Page

▓

Ted Peters directs traffic at the intersection of science, religion, and ethics. Peters is an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union, where he co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. He authored Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom? (Routledge, 2nd ed., 2002) as well as Science, Theology, and Ethics (Ashgate 2003). Along with Martinez Hewlett, Joshua Moritz, and Robert John Russell, he co-edited, Astrotheology: Science and Theology Meet Extraterrestrial Intelligence (2018). Along with Octavio Chon Torres, Joseph Seckbach, and Russell Gordon, he co-edited, Astrobiology: Science, Ethics, and Public Policy (Scrivener 2021). He is also author of UFOs: God’s Chariots? Spirituality, Ancient Aliens, and Religious Yearnings in the Age of Extraterrestrials (Career Press New Page Books, 2014). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

▓

Works Cited

Atkins, P. (2006). Atheism and Science. In e. Philip Clayton and Zachary Simpson, The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Science (pp. 124-136). Oxford UK: Oxford University Press.

Bohm, D. (1951). Quantum Theory. New York: Prentice Hall.

Bohm, D. (1952). A Suggested Interpretation of the Quantum Theory in Terms of Hiddon Variables I and II. Physical Review 85, 166-193.

Bohm, D. (1980). Wholeness and the Implicate Order. London: Routledge.

Bohm, D. (1988). Postmodern Science and a Postmodern World. In e. David Ray Griffin, The Reenchantment of Science (pp. 57-68). Albany NY: SUNY.

Bohm, D. (1990). A New Theory of the Relationship of Mind and Matter. Philosophical Psychology, 3(2), 271-286.

Bohm, D. a. (1994). The Undivided Universe: An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum theory. New Brunswick NJ: Rutgers University Press.

O’Murchu, D. (2021). Quantum Theology: Spiritual Implications of the New Physics. New York: Crossroad.

Polkinghorne, J. (2006). Quantum Theology. In e. Ted Peters and Nathan Hallanger, God’s Action in Nature’s World: Essays in Honor of Robert John Russell (pp. 137-145). Aldershot UK: Ashgate.

Russell, R. J. (1985). The Physics of David Bohm and Its Relevance to Philosophy and Theology. Zygon 20:2, 135-158.

Russell, R. J. (2008). Cosmology from Alpha to Omega: The Creative Mutual Interaction of Theology and Science. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press ISBN 978-0-8006-6273-8.

Stapp, H. P. (2017). Quantum Theory and Free Will. Switzerland: Springer.