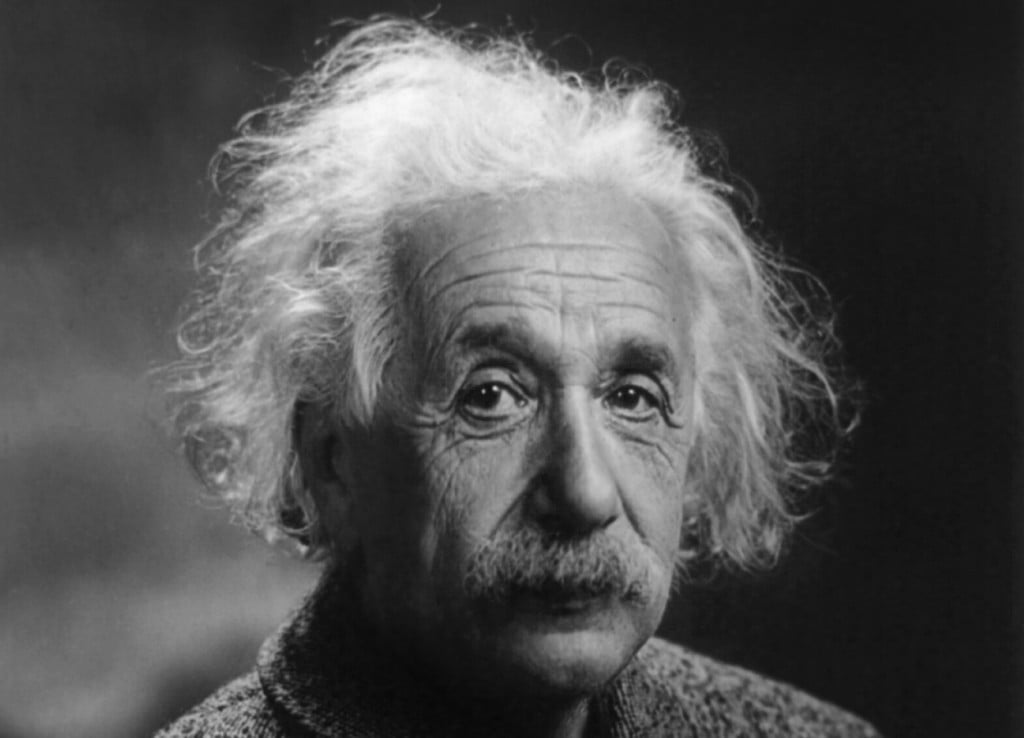

I bet on completing a PhD in the humanities. Therefore, I am a betting man. As such Einstein’s retort to quantum mechanics, “God doesn’t play dice,” always seemed a bit Puritan to me.

According to Max Jammer, Einstein’s bon mot was religiously motivated. Religion was one of the physicist’s major intellectual obsessions outside of his day job of revolutionizing everything we know. Jammer even wrote a book, Einstein and Religion: Physics and Theology, about how Einstein not only engaged religion all of his life, but also how his theory of relativity might transform theological thinking itself.

Einstein and Religion’s sent me on a search for modern physics-inflected theology, which resulted in disappointment.

I’ve discovered that modern theology–with the notable exceptions of Ian Torrance (Space, Time, and Resurrection), Wolfhart Pannenberg (Toward a Theology of Nature), and Fr. Michal Heller (Infinity: New Research Perspectives)–hasn’t put much effort into integrating Einstein’s insights into theological thinking. For whatever reasons, theology hasn’t gambled much on physics.

The theme of gambling keeps returning regularly in my life.There is the looming Powerball jackpot, which is an integral part of my financial planning to pay off my college debts. I also saw a picture of Ella Fitzgerald jailed for gambling. Pascal’s gamble on practicing piety, whether you fully believe or not, is part of my resolution to pray and read more and write less.

Ulrich Lehner’s forthcoming The Catholic Enlightenment is part of my gamble upon reading more. It the academic orthodoxy overturning story of how 18th century Catholics–extending Trent and looking forward to Vatican II and Pope Francis–gambled upon education and structural reform in order to make Catholicism both more faithful to its roots and more open to critically engaging the modern world.

One of the more amusing anecdotes in Lehner’s country by country survey in The Catholic Enlightenment is the following speech the Catholic Enlightener Galiani was supposed to have given in response to the mocking skepticism of Denis Diderot at a dinner party:

Let us suppose . . . that he among you who is most convinced that the world is a work of chance is playing dice, not in a gambling house but in the most honorable home in Paris, and that his opponent gets seven twice, three times, four times, and keeps on constantly. After the game lasts for a while, my friend Diderot, who is losing his money, will not hesitate to say: “The dice are loaded, I am among cutthroats!” “Ah, Philosopher, what are you saying!” Because ten or twelves throws have left the dice box in such a way as to make you lose six francs, you believe firmly in an artificial combination, in a well-organized swindle, and on seeing in this universe universe so prodigious a number of combinations, a thousand and thousand more difficult and more complicated and more lasting, and more useful, you do not suspect that the dice of nature are also loaded and that there is up there a great thief who makes a game out of catching you.

Lehner’s comments upon the scandal this speech probably gave to the very group it was supposed to defend:

For the average Catholic it was, of course, blasphemous to call God a “thief”” or a “rascal”–yet by shocking his listeners, many of whom had become indifferent to a belief in God, he made them think, attracted laughter, and earned intellectual respect.

That is, if we assume, the average Catholic forgets that Jesus, ever the rascal by our human expectations, told a parable comparing the return of the Son of Man to a thief in the night.

Isn’t it also a big gamble to put yourself in the hands of such a God? Maybe the cheating of our expectations of such a God was blasphemous to Einstein? [If you want to see more of the unexpected see the book Disturbing Divine Behavior.]

Here’s an acquaintance, and author of the Uncontrolling Love of God, with yet another possible take on the Einstein comment:

You might also want to take a look at my exhaustive list of books (way more than 20) on the wide range of dialogue between contemporary theology and science.