Resentment vs Compassion

PT 3201. Part 1: From Resentment to Ressentiment

Resentment [otherwise known as ressentiment] vs Compassion. Are they opposites? Or are they partners? The public theologian is asking.

I’d like to think through these two ideas with you the reader. On the one hand, resentment and compassion look like opposites. But, on the other hand, sometimes we get all riled up when we witness an injustice. We feel compassion for the victims of injustice. If we feel helpless in the face of perfidy, then a visceral resentment rises up. Isn’t this the way we should feel about injustice? Mmmmm?

One thing we know for certain is that Scripture enjoins us to be compassionate. “Finally, all of you, live in harmony with one another. Be sympathetic. Love as brothers. Be compassionate and humble” (1 Peter 3:8).

But does Scripture enjoin us to be resentful too? Not exactly. One thing about resentment that is relevant is this: resentment is a feeling prompted by injustice. Justice is important to the Bible, isn’t it? You betcha! Could resentment be holy? Saintly? Virtuous?

As an exercise in public systematic theology, let’s follow the trail of resentment to see where it leads. Along the trail, we’ll look over the cliffs. We’ll explore the downside of resentment. Then, we’ll turn on to the compassion trail. Might a healthy resentment toward injustice return at this point? Where will these trails lead us?

When looking over the cliffs, some ravines will require patient orienteering. One such ravine is Christian nationalism as we find it in Russia and America. Another ravine is the ideology of social justice embraced by white ‘n’ woke progressive Christianity. There, we will subject the unhappy consciousness discourse clarification, revealing how it twists and gnarls and disguises progressive resentment.

Here’s what to expect.

Resentment vs Compassion. Part 1: From Resentment to Ressentiment

Resentment vs Compassion Part 2: From Ressentiment to Reparations

Resentment vs Compassion Part 3: Russian Christian Nationalism

Resentment vs Compassion Part 4: American Christian Nationalism

Resentment vs Compassion. Part 5:” Ressentiment in the White ‘n’ Woke Unhappy Consciousness

Resentment vs Compassion. Part 6: Ressentiment with Copmpassion

Resentment vs Compassion Part 7: Christian Natiionalism’s Decline Narrative

Resentment vs Compassion Part 8: The Unhappy Consciousness Narrative

Resentment vs Compassion Part 9: To Slay the Christian Nationalist Dragon

Resentment vs Compassion Part 10: Don’t trust your pastor

Resentment vs Compassion Part 11: Christian Nationalism vs Anti-Christian Nationalism

Resentment vs Compassion Part 12:. A More Compassionate America? Trump Tyranny.

Resentment vs Compassion Part 13: Christian Nationalism versus the Vermin Curse

Resentment is an evil to be shunned, Right?

Resentment seems to be an evil thing. Resentment is “the result of envy,” says philosopher Eric Buys. “It relies on mimesis and mimetic desire” to have what others want. In short, resentment is born of coveting.

According to Gene Veith’s Cranach Blog, resentment is what mass shooters share in common. Resentment empowers loners to do grave evil.

“There is nothing good or useful about resentment,” complains another Patheos blogger, J.E. Dyer. “But peoples the world over have come to enshrine it in their politics, and the West—including America—has made a special art of it in the last 100 years.” Dyer warns us to “just say ‘no’ to resentment.

Resentment is something we repent from. Rachel Popcak and Gregor Popcak offer us a handy-dandy list of five steps for saying ‘no’ to resentment in our daily life.

- Forgiveness

- Make a plan for healing embittered relationships

- Stop dwelling and retelling

- Seek grace

- Seek professional help

Pretty good advice, eh!

On her Family Channel, Terry Gaspard, tells us how to let go of resentment and achieve a happy marriage. If you want your spouse to be happy, get rid of that resentment.

It appears that I’m barking up the wrong tree by trying to connect resentment with justice. Right?

From Resentment to Ressentiment

Things can get more complicated. First, think of resentment as a single strand of fettucine . It’s simple. Straight forward envy or hatred sometimes combine with secret plans to commit revenge.

Now, secondly, imagine ressentiment. The word is French. In ressentiment we re-feel a past injustice in such a way that it incites resentment. With ressentiment we add nuances, connotations, political ideology, scapegoating, and mob violence. The result is a full bowl of fettucine with all the strands intertwining. Shall we begin untwining? Could German philosopher Max Scheler (1874-1928) help in our untwining?

“Ressentiment is a self-poisoning of the mind… It is a lasting mental attitude, caused by the systematic repression of certain emotions and affects which, as such, are normal components of human nature. Their repression leads to the constant tendency to indulge in certain kinds of value delusions and corresponding value judgments. The emotions and affects primarily concerned are [as quoted above] revenge, hatred, malice, envy, the impulse to detract, and spite.” (Scheler 1915, 1994). Cited by Martin Marty.[1]

Recently, evangelical Patheos columnist Anthony Costello appealed to the French ressentiment to analyze Critical Race Theory (CRT). CRT appeals to the emotions, observes Costello. This makes it politically potent. “Resentment is an emotion that has a lot going for it in the realm of politics,” he observes. When a group perpetually re-feels an injustice, the group can become a mob. Those who support CRT may take issue with Costello here.

Still we must ask: what do we feel when joining the political mob? We feel “revenge, hatred, malice, envy, the impulse to detract, and spite.” That’s what public theologian Martin Marty observes.

“These are not new in politics, religion, or culture, but, taken together, they appear to be grounded in profound, bone-deep, soul-destroying resentment, and are efficiently mobilized by modern media, on the internet, and with expensive advertising. The analysts point to the special character of our current explosions and often render their view technical by using the French word ressentiment.”

In short, resentment in the form of ressentiment is based on re-feeling a past injustice that stimulates our emotions to right the injustice with…? With what? Recompense? Punishment? Violence? Acting on the feeling of resentment could never partner with compassion. So it seems.

Compassion is a good to be embraced, Right?

Rather than resentment, compassion should be the trait that characterizes the Christian life. Evangelical columnist Jack Wellman collects Bible verses such as Matthew 9:36 that inspire us to become compassionate persons. Here’s Wellman’s take on compassion.

“The word ‘compassion’ is a compound word meaning with (con) passion (great love and pity). The Greek word for compassion used in the New Testament is splagchnizomai, and this verb means ‘to be moved from the bowels’ which is a Jewish idiom meaning ‘having deep compassion’ since they believed the bowels were thought to be the seat of emotions like love and pity. Don’t we feel something in our stomach when we are moved greatly with passionate feelings like grief, sorry, heartache, pain or sympathy? This is not feeling sorry for someone necessarily but it is having a deep, abiding compassion for people and their plight in life.”[2]

Now, let me make an observation. Both resentment and compassion share something important in common. Both rely on feeling. More precisely, both rely on re-feeling. In resentment, we re-feel a past injustice. In compassion, we re-feel someone else’s pain.

This re-feeling draws up into our consciousness a suffering that occurs in another time or in another place. Sometimes it’s the re-feeling of another person. Just where might this observation about re-feeling lead us?

Appealing to Two 20th C. Roman Catholic Giants

Might giants help us untwine the strands? Well, maybe their fingers will be too big and too thick to do fine things. But, let’s ask them anyway.

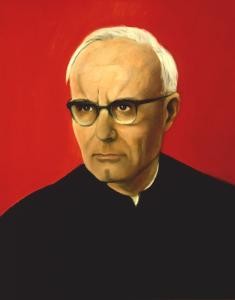

Theological giants walked the earth during and immediately following World War II. Among German speaking Roman Catholics, one giant was Karl Rahner (1904-1984). Along with bright lights such as Yves Congar, Henri de Lubac, and Marie-Dominique Chenu, Rahner’s Nouvelle Théologie illuminated the road leading to the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965). Despite the fact that some elements of Nouvelle Théologie were condemned in the encyclical Humani generis by Pope Pius XII, Rahner made a significant impact on The Second Vatican Council and the ecumenical luminance that followed.

We remember Rahner for emphasizing divine incomprehensibility. “God is incomprehensible. But the vision of the mystery in itself, accepted in love, is the beatitude of the creature, and it alone makes the One who is known as mystery the inconsumable thorn bush of the eternal flame of love” (Rahner 1978, 217).

While I was a graduate student, Rahner came to the University of Chicago and delivered a lecture on “The Incomprehensibility of God.” My Jesuit colleague, Otto Hentz, remarked, “Next week we should invite God to lecture on ‘The Incomprehensibility of Karl Rahner’.”

That’s the German, Rahner. For English speaking Roman Catholics, the giant was Canadian Bernard Lonergan (1904-1984). Lonergan taught at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome, Regis College in Toronto, Boston College, and Harvard University. His two most influential works were Insight (1957) and Method in Theology (1972). I discovered I lack sufficient insight to understand Insight. But the much more accessible Method in Theology has become one of the bibles I rely on for theological methodology.

During my stint as a faculty member at Loyola University in New Orleans, the Jesuit disciples of Bernard Lonergan met almost weekly to discuss one or another esoteric detail of the master’s complex epistemology. I affectionately referred to them as the “Lonergonads.” The Lonergonads invited me to join. I accepted. I learned much. And I appreciated more. Still do.

Lonergan on Ressentiment

Let’s turn to Bernard Lonergan to untangle ressentiment. Lonergan elects the French term and describes resentment as “a development of feelings.” He traces the concept of ressentiment in two German thinkers, Friedrich Nietzsche and Max Scheler. Most scholars do.

“Ressentiment is a re-feeling of a specific clash with someone else’s value-qualities. The someone else is one’s superior physically or intellectually or morally or spiritually. The re-feeling is not active or aggressive but extends over time, even a life-time. It is a feeling of hostility, anger, indignation that is neither repudiated nor directly expressed. What it attacks is the value-quality that the superior person possessed and the inferior not only lacked but also feels unequal to acquiring. The attack amounts to a continuous belittling of the value in question, and it can extend to hatred and even violence against those that possess that value-quality….This distortion can spread through a whole social class, a whole people, a whole epoch” (Lonergan 1972, 33).[2]

Note some of the salient traits of ressentiment: clash of value-qualities; resentment toward someone superior; belittling the value of the superior; hatred; potential for violence. This seems to apply to the underclass who resents its overlords.

That’s simple. Or, is it? Actually, it gets quite complicated, nuanced, and almost imperceptible. Let’s look first at a straightforward and perceptible example: the demand for reparations.

This post in the Resentment vs Compassion series is PT 3201. Part 1: From Resentment to Ressentiment

What’s Next?

Here in Part 1 of our series of posts on “Resentment vs Compassion,” we point out that our English term, ‘resentment’, is like a single strand of fettuccini. It’s simple: when we envy someone else’s privilege we might be motivated to take revenge. When we turn to the French, ‘ressentiment‘, we get an entire bowlful of fettuccini with all strands intertwined. Our task has been to untwine ressentiment‘s nuances, connotations, political ideologies, scapegoating, and perhaps mob violence.

Yet, we are asking: might there exist a dimension of ressentiment within compassion? After all, in both ressentiment and compassion we re-feel what victims of injustice feel?

Here is my working hypothesis guiding the series on Resentment and Compassion as well as the series on Measuring Christian Nationalism:

Progressive Christians Against Christian Nationalism (CACN) are displacing their anger at Donald Trump onto evangelicals by painting evangelicals with the colors of Christian nationalism. That is, CACNers blame white evangelicals for Christian nationalism.

What’s next? In Part 2 we will watch the fettuccini strands tie together in African American reparation demands, Great Replacement Theory, and in the entangled xenophobic rhetoric of former U.S. President Donald J. Trump. Then, in later posts, we will untwine the fettuccini strands of Russian Christian nationalism, American Christian nationalism, and the unhappy consciousness pervading white ‘n’ woke progressive Christianity.

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor, teaching theology and ethics. He is author of Short Prayers and The Cosmic Self. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters’ fictional series of espionage thrillers features Leona Foxx, a hybrid woman who is both a spy and a parish pastor.

▓

Notes

[1] Ideology twists our morality. “Ressentiment brings about its most important achievement when it determines a whole morality, perverting the rules of preference until what was evil appears to be good…Christian values can very easily be perverted into ressentiment values and have often been thus conceived. But the core of Christian ethics has not grown on the soil of ressentiment” (Scheler 1915, 1994, 28).

References

Deane-Drummond, Celia. 2017. “Empathy and the Evolution of Compassion,” Zygon 51:1:258-178.

Fassin, Didier. 2013. “On Resentment and Ressentiment.” Current Anthropology 54:3 249-267.

Kelly, Casey Ryan. 2020. 2-24. “Donald J. Trump and the rhetoric of ressintement.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 106:1 file:///C:/Users/Ted/OneDrive/Documents/My%20Research/Kelly%20Trump%20Ressentiment.pdf.

Lonergan, Bernard. 1972. Method in Theology. New York: Herder and Herder.

Peters, Ted. 1993. Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society. Grand Rapids MI: Wm B Eerdmans.

Rahner, Karl. 1961-1988. Theological Investigations. 22 Volumes. New York: Seabury.

—. 1978. Foundations of the Christian Faith. New York: Seabury Crossroad.

Scheler, Max. 1915, 1994. Ressentiment. Marquette: Marquette University Press: file:///C:/Users/Ted/OneDrive/Documents/My%20Research/Scheler%20Max%20Ressentiment.pdf.