What is Public Theology?

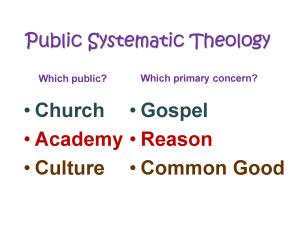

What is public theology? If you’ve been following this column perhaps you’ve read something like this ad nauseum: Public Theology is conceived in the church, critically reasoned in the academy, and offered to the wider culture for the sake of the global common good.

What is public theology? If you’ve been following this column perhaps you’ve read something like this ad nauseum: Public Theology is conceived in the church, critically reasoned in the academy, and offered to the wider culture for the sake of the global common good.

I like this description because I believe that some doctrinal loci within systematic theology–especially our theological understanding of the dialectic within human nature between the imago Dei and the propensity for sin–can be illuminative for understanding repressive social structures, political tensions, and the worldwide outcry for justice.

I like this description because I believe that some doctrinal loci within systematic theology–especially our theological understanding of the dialectic within human nature between the imago Dei and the propensity for sin–can be illuminative for understanding repressive social structures, political tensions, and the worldwide outcry for justice.

With this in mind, I would like to acknowledge an anniversary that’s probably not on your calendar. Six years ago on October 23, 2016, Jayme R. Reaves [whom I don’t know] posted a succinct and accurate description of Public Theology. He answered our question — what is public theology? — this way.

“If theology in its most basic sense is the study of God, then, also in its most basic sense, public theology is the study of God done by or for the public, or as it pertains to issues in the public sphere. Public theology is theology about and for the public. If something is a public issue, public theology has something to say about it.”

Reaves drew some corollaries. I’ll select only one for mention here. Public theology, said Reaves…

“does not seek to give preference to Christianity but to witness to values that Christians believe are important for the common good.”[2]

The Question of Authority

When the theologian speaks to the wider culture and not to the church, the question of authority arises. Outside the church, no one is obligated to respect the authority of the Bible. No one is obligated to respect the authority of religious symbols deriving from any religious tradition. Since the sex abuse scandals two decades ago followed by the rise of vicious atheism and now the blight of religious nationalisms, ‘religion’ has become a cuss word. If anything, the theologian is contaminated by disrespect in the public square.

Since the 9/11 catastrophe of 2001 and the atheist blaming of all religions, religion is popularly identified with violence. Society can blame religious competition for the violence we read about in human history. In this setting, the public theologian dare not attempt to speak with authority outside the religious community.

To address the wider culture requires appeal to the highest ideals already at work in the culture. That is, the public theologian appeals to God’s law already built into creation.

God’s Law in its Political Use, Not the Gospel

Now, a Christian public theologian loves Jesus and desires to share the gospel, to be sure. The gospel is the story of Jesus told with its significance. The significance of the story of Jesus is that by God’s grace we can look forward to new creation, justification, and proclamation. The gospel is the Church’s gift to both itself and the wider world. But…

The public theologian is not in the business of giving the gospel to the world, at least not primarily. Rather, the public theologian interprets God’s law in an intelligible and inspiring fashion so that all persons of good will, Christian and non-Christian, perceive the law’s wisdom and strive to serve the common good.

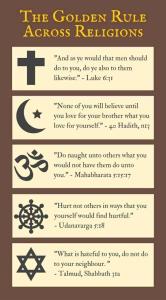

God’s law can be found in the 10 Commandments, the moral codes of many religions, the minds of rational persons who stop to think about it, and common sense. The Golden Rule, for example, comes to articulation not only in Jesus but most of the world’s traditions: treat others as you would want them to treat you.

Does this mean the Golden Rule built into creation? Yes, says Martin Luther. “Nature teaches–as does love–that I should do as I would be done by [Luke 6:31]”(Luther, 1523, 45:128). The takeaway here is this: when the public theologian appeals to God’s law, it will be understandable by the wider public. The task of the public theologian in the midst of social tension is to call upon our better natures, so to speak. To call upon God’s law which always lies ready to hand. Danish theologian Regin

“The Old Testament teaches “natural law (lex naturae), a law which serves God’s purpose for creation, serves to promote blessing and life and to thwart damnation and death….The commandment of love to God and the neighbor sets forth the very order of creation”(Prenter, 202).

For Lutherans, and Calvinists too, God’s law serves to create and maintain community. What the Lutherans call the first use and the Calvinists the second use of the law is to serve the polis or civitas). It is called the “political use” (usus politicus) or “civil use” (usus civilis) of the law. By invoking this use of God’s law, the public theologian lifts up human community oriented around the common good.[2]

The public theologian is called upon to make creative application of God’s law to the contemporary cultural situation. Christine Helmer at Northwestern University and former Martin Marty Fellow at the University of Chicago makes this point forcefully.

“Critical reason is thus free to imagine possibilities for human existence, and to construct modes of engagement. From this contemplative distance from politics, theologians can then also reflect on the distinction between church and world, and the difference in theological prescription that each area entails” (Helmer 2022, 284).

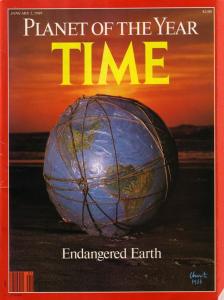

The Global Common Good

What our planet desperately needs now is human commitment to the global common good. Short-sightedness, selfishness, and willful denial of climate change over seven decades has turned the human race into an audience watching Planet Earth degrade and degrade in its capacity to support life as we’ve known it. To grasp and embrace the scope and value of the common good, we need to turn to the Roman Catholics. “The term ‘common good’ is associated with Roman Catholic social thought,” Gene Veith rightly observes. Pope Paul VI defined the common good as “the sum of those conditions of social life which allow social groups and their individual members relatively thorough and ready access to their own fulfillment.”

Or, as Jesuit David Hollenbach puts it:

The common good is “the set of conditions that facilitate social living by which persons or groups are enabled to more fully and readily achieve their goals and perfection”(Hollenbach, 1977, 211)

In our era when we face the eco-crisis, the public theologian must lift up a vision of the global common good. When it comes to projecting a vision of a just, sustainable, participatory, and planetary society, the public theologian can rely on people of good will in most all of the world’s religious traditions. Here are Dharma scholars, Rita Sherma and Purushottama Bilimoria.

“Amongst the diverse resources of religious worlds for such an effort are (1) an inherent critique of consumption and hyper-materialism by the sacred texts of almost all religions; (2) emphasis on community rather than self-centeredness; (3) elevation of simplicity rather than hyper-consumptive materialism; and (4) an integral relationship to nature espoused by sources as diverse as the Shinto philosophy of interrelated intricacy, Buddhist metaphysics, the theology of St. Francis of Assisi, Judaism’s principle of the Jubilee (the year at the end of seven cycles of shmita), and the human ecology of the Hindu Vedas” (Sherma 2022, 39).

Planet Earth is the most public object I can think of. It’s the global common good for which public theologians of different religious traditions join hands in lifting up. The Christian public theologian will find partners of good will along the way.

What is Public Theology? More Resources

For more resources, click that mouse!

Manifesto Articles on Public Theology

Videos on Public Systematic Theology

▓

Ted Peters pursues Public Theology at the intersection of science, religion, ethics, and public policy. Peters is an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union, where he co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He previously authored Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom? (Routledge, 2nd ed., 2002) as well as Science, Theology, and Ethics (Ashgate 2003). He is editor of AI and IA: Utopia or Extinction? (ATF 2019). Along with Arvin Gouw and Brian Patrick Green, he co-edited the new book, Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics hot off the press (Roman and Littlefield/Lexington, 2022). Soon he will publish The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com. His fictional spy thriller, Cyrus Twelve, follows the twists and turns of a transhumanist plot.

▓

Notes

[1] Similarly, according to Paul S. Chung, “In a nutshell, public theology (theologia publica) is concerned with the public affairs or institutions of society (res publica) to promote the common good of society”(Chung, 2022, 11).[2] The theological or pedagogical use of the law for both Lutherans and Calvinists is to reveal our sinfulness and our need for God’s grace. Here we find the divine law in dialectical interaction with the message of the gospel. “The law commands and demands of us what we are to do….The gospel, however, does not preach what we are to do or to avoid. It demands nothing of us, but instead reverses the matter, does the opposite, and says, ‘This is what God has done for you’.” (Luther, 2:133-134).

References

Chung, Paul S., 2022. Public Theology and Civil Society: Constructive Formation. Madrid: EBL.

Helmer, Christine, 2022. “Luther, Politics, and the Production of Theological Knowledge.” The Crux of Theology: Luther’s Teaching and Our Work for Freedom, Justice, and Peace. Ed.s., Alan E. Jorgenson and Kristin E. Kvam. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Hollenbach, David, S.J., 1977. “Modern Catholic Teachings Concerning Justice,” The Faith that Does Justice. Ed., John C. Haughey. New York: Paulist.

Luther, Martin, 1523. “Temporal Authority: To What Extent It Should Be Obeyed.” LW.45.

Luther, Martin, 1525. “How Christians Should Regard Moses” (1525). Tr. Brooks Shramm. The Annotated Luther. Eds., Hans J. Hillebrand, Kirsi J. Stjerna, Timothy J. Wengert. 5 Volumes: Minneapolis MN: Fortress, 2015; 2:127-152.

Prenter, Regin, 1967. Creation and Redemption. Tr. Theodore Jensen. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Sherma, Rita, and Purushottama Bilimoria, eds., 2022. Religion and Sustainability: Interreligious Resources, Interdisciplinary Responses. Switzerland: Springer.