The Soul of Benedict XVI

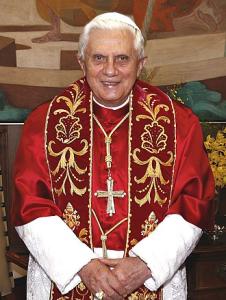

His Holiness, Pope Benedict XVI (1927-2022) has just passed from the Church Militant to the Church Triumphant on December 31, 2022.

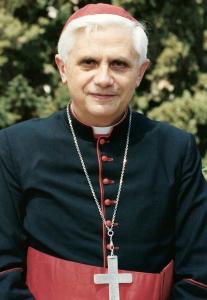

I never met this pontiff. But I did hear him lecture once at the University of Munich. At that time we knew him as Joseph Cartinal Ratzinger, the august systematic theologian from Bavaria.

Toward the end of the last century Cardinal Ratzinger served as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, previously known by historians as the Inquisition. Despite his notorious reputation for instilling fear when swinging the sword of truth, I greatly admired Ratzinger’s theological acuity.

Prior to his turn–what Germans call a Kehre–somewhere around 1968, Ratzinger’s voice was heard promoting an ecumenical and even liberal agenda. But, the swing of student movements toward Marxism in the 1960s turned modern culture against the Church. Secularisation became materialistic, ideological, and totalitarian. Like other German intellectuals of the era such as Wolfhart Pannenberg, theologian Ratzinger took a swing to the right to avoid the left. Ratzinger felt the urgent need to protect the wisdom and authority of classical Christian doctrine from getting blown away by the stormy winds of modernity, relativism, and pluralism.

In this brief memorial in a time of many memorials, I dare not try to be exhaustive. Rather, I’d like to mention just two of my favorite discussions–both on the nature of the human soul–from the Ratzinger era: (1) the soul versus the resurrection of the dead and (2) the soul in ensoulment at conception.

(1) Immortality of the Soul or Resurrection of the Dead?

I like a book Joseph Ratzinger co-authored with Johan Auer, Eschatology: Death and Eternal Life. Specifically, I like their sophisticated analysis of the soul. Despite references to Plato, substance dualism is rejected. Rather, in the tradition of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, Auer and Ratzinger viewed the soul as the form of the body. The soul is not a separate non-bodily substance. The soul is a substance as the form that animates the body, they said. “Being in the body is not an activity, but the self-realisation of the soul” (Auer 1988, 148).

Despite this theology of the soul, curiously, prayers of the faithful these days are being offered up for the soul of Benedict XVI.

Having given a great deal of attention to eschatology, I’ve found substance dualism with its soulechtomy at death inadquate. In place of a soulechtomy–where the ethereal soul flies away from the body at death–Auer and Ratzinger proffer resurrection of the body. Furthermore they see in the New Testament what I think I see, namely, Jesus’ past resurrection and our future resurrection are ontologically joined. There is only one resurrection. But, it’s divided into two phases. Jesus’ Easter ressurection is phase one. Ours is phase two. According to Auer and Ratzinger:

“The resurrection of Christ and the resurrection of the dead are not two discrete realities but one single reality which in the end is simply the verification of faith in God before the eyes of history” (Auer 1988, 116).

This is where I like to take advantage of the word, prolepsis. Jesus’ Easter resurrection was a proleptic anticipation of the final and universal resurrection. What happened to Jesus on the first Easter in his person will happen universally in the future. Rather than an escape of the soul from the physical body, the Christian promise is the redemption of the entire physical creation accompanied by the resurrection of the bodies of the forgiven sinners.

Prolepsis became the uniting thread that weaves together all the doctrinal loci in my own systematic theology. The gospel, as I understand it, announces the preactualization of the future consummation of all things in Jesus Christ. On Easter, the world was given God’s promise that in the future all things will be made whole. The promise comes to us through Jesus who died on Good Friday and rose from the dead on Easter Sunday. As prolepsis, Jesus Christ embodies the promise because he anticipates in his person the new life that we humans and all creation are destined to share.

I think Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger got this one right.

(2) Ensoulment at Conception?

But, I don’t think Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger and his Vatican colleague, Saint John Paul II, got it right in the stem cell controversy.

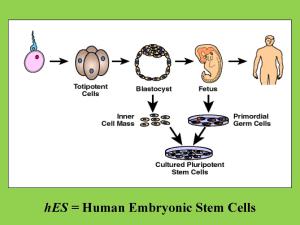

Here is the bioethical question: should genetic scientists harvest human embryonic stem cells (hES cells) to regererate human organs in the service of human health and well-being? The Vatican asks and aswers this question in the “Declaration on the Production and the Scientific and Therapeutic Use of Human Embryonic Stem Cells” document.

“Is it morally licit to produce and/or use human embryos for the preparation of ES cells? The answer is negative….the ablation of the inner cell mass of the blastocyst, which critically and irremediably damages the human embryo, curtailing its development, is a gravely immoral act and consequently is gravely illicit” (Pontifical Academy of Life 2000).

Richard Doerflinger, a policy developer for the U.S. National Conference of Catholic Bishops, reinforces the anti-hES cell policy: “intentional destruction of innocent human life at any stage is inherently evil, and no good consequence can mitigate that evil” (Doerflinger 2001, 143).

Is there a back story? You betcha. And Benedict XVI is its author.

In the 1970’s and the 1980’s, pro-life Ratzinger along with the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith were locked in battle with pro-choice forces over abortion-on-demand. In defense of the unborn embryo, Ratzinger made two moves.

First, at the moment of conception ensoulment takes place and the conceptus takes on the imago Dei. That is, at the moment of conception you and I begin to bear God’s image.

Second, the presence of the imago Dei ontologically justifies the moral doctrine of human dignity. Because the conceptus possesses the image of God, the early embryo must be treated as a moral end and not a means to some further end. Every fertilized egg deserves the right to life, accordingly. The right to life of the ensouled embryo trumps the right of the mother to make a choice whether to abort or not. This was the bottom line of Donum Vitae in 1987.

“…recent findings of human biological science…recognize that in the zygote resulting from fertilization the biological identity of a new human individual is already constituted. Certainly no experimental datum can be in itself sufficient to bring us to the recognition of a spiritual soul; nevertheless, the conclusions of science regarding the human embryo provide a valuable indication for discerning by the use of reason a personal presence at the moment of this first appearance of a human life: how could a human individual not be a human person?”Donum Vitae.

That was 1987. Now, let’s leap forward to August 1998 and the first isolation of hES cells at the University of Wisconsin and the dawn of the stem cell era. These human embryonic stem cells are derived in the laboratory by disaggretating the embryo at the blastocyst stage, which is four to six days after conception. The inner cell mass is preserved, but the embryo itself gets destroyed. Does this mean that a human person possessing the imago Dei is destroyed? Does this mean that the dignity of the potential child is violated? Does it mean that geneticists are baby-killers?

When John Paul II and the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith along with other moral theologians oriented toward Vatican policy weighed in on cloning and stem cells and related issues late in the 1990s, they appealed again and again to two precedents, Donum Vitae (1987) and Evangelium Vitae (1995). The central tenet in both is this: morally protectable human personhood becomes applied to the conceptus or zygote, the egg fertilized by the sperm.

“The Church has always taught and continues to teach that the result of human procreation, from the first moment of its existence, must be guaranteed that unconditional respect which is morally due to the human being in his or her totality and unity in body and spirit: The human being is to be respected and treated as a person from the moment of conception; and therefore from that same moment his rights as a person must be recognized, among which in the first place is the inviolable right of every innocent human being to life” (Pope John Paul II 1995).

I suspect that Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger whispered into the ear of his pontiff pal so that the two popes showed consistent defense of the fertizied egg at conception. Destruction of the early embryo to harvest its stem cells even for the purpose of therapy violates its dignity. It is illicit to abort such an embryo in the woman’s body. Therefore, it becomes illicit in the laboratory to disaggregate this early embryo in order to harvest its stem cells. In sum, the anti-abortion argument became, for Ratzinger, the anti-stem cell argument.

I think Joseph Cardinal Ratziner’s leadership was misleading on this one.

Roman Catholic Bioethicists in the Stem Cell Controversy

At the time, I felt the cardinal and the pope were mistaken. Out of some grant money I oversaw at the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences in Berkeley, I awarded about sixty-thousand dollars to premier bioethicist Al Jonson. We gathered about fifteen influential Roman Catholic moral theologians for a three-day meeting at Santa Clara University in California. We asked embryologists and geneticists from Stanford and the Geron Corporation to present what is known scientifically about fertilization and individuation in embryonic development. Scientifically speaking, the experts reported, we cannot locate the moment of ensoulment. We can hardly locate the moment of individuation.

Individuation is important here. Why? Because the Vatican had described ensoulment this way. When the unique genome of the father unites with the unique genome of the mother, these two then call out for a spiritual soul. God infuses the soul, producing a unique individual. Individuation and ensoulment belong together, according to the Vatican.

Here’s the problem. There is no individual human person at conception. One conceptus can produce genetically identical twins, quadruplets, and more. There is no individual until the 14th day (somewhere between the 12th and 14th day after conception) when the fetus attaches to the uterine wall of the mother.

What does this imply? It implies that an individual human person is not established in the laboratory when the zygote is activated. An individual appears only in the body of the mother on the 14th day after conception. If ensoulment establishes a human individual possessing the imago Dei warranting the protection of dignity, it occurs only within the mother’s body and on the 14th day. This means, among other things, that imputing dignity at conception finds no corroboration with what is known scientifically.

Once these matters had been presented, the Roman Catholic bioethicists met in caucus. They voted down a motion to publish a statement. The majority agreed that this information would be too inflamatory. They felt they needed to walk gingerly in front of then Pope John Paul II and yet-to-be-elected Pope Benedict XVI.

Along with my colleagues, Karen Lebacqz and Gaymon Bennett, I decided to write up our own notes and parse the arguments with utmost precision. The three of us eventually published a co-authored book, Sacred Cells? Why Christians Should Support Stem Cell Research.

As I said, I think Joseph Cardinal Ratziner’s leadership was misleading on this one.

Was Benedict XVI consistent on the ontology of the soul?

I ask: how did Pope Benedict XVI reconcile these two positions? In the first discussion on resurrection of the body, theologian Ratzinger seemd to side with Aristotle over against Plato on the ontological status of the soul. The soul only animates the body. When we die, we die entirely. Totally. No soul survives. What God promises, then, is a future resurreciton of the whole person: body, soul, and spirit. Frankly, this holistic view fits what most post-neoorthodox–both Roman Catholic and Protestant–theologians have concluded.

I ask: how did Pope Benedict XVI reconcile these two positions? In the first discussion on resurrection of the body, theologian Ratzinger seemd to side with Aristotle over against Plato on the ontological status of the soul. The soul only animates the body. When we die, we die entirely. Totally. No soul survives. What God promises, then, is a future resurreciton of the whole person: body, soul, and spirit. Frankly, this holistic view fits what most post-neoorthodox–both Roman Catholic and Protestant–theologians have concluded.

But, when we turn to the stem cell discussion, I wonder if Ratzinger maintained sufficient consistency. Because the soul–including the imago Dei–gets imparted at conception, the soul sounds like a thing. Ratzinger seemes to presuppose that the soul enjoys a disembodied and independent existence that gets added to a body at conception. In Donum Vitae, Ratzinger sounds a bit more Platonic or even Cartesian than Aristotelian.

The Kehre of Benedict XVI

The problem with liberal theology, the post-Kehre Benedict XVI complained, is that accomodation to the surrounding culture risks loss of integrity if the culture turns totalitarian. When criticizing the Deutche Christen movement of the 1930s (German Christians who followed Adolf Hitler), Ratzinger issued a historical judgment and then a warning.

“Liberal accomodation…quickly turned from liberality into a willingness to serve totalitarianism…a church without theology impoverishes and blinds, while a churchless theology melts away into caprice” (Cited in Allen, 31).

Biographer John Allen is unhappy with this Ratzinger Kehre.

“How does one move from Ratzinger, the progressive firebrand, to Ratzinger the chief inquisitor?…Ratzinger’s life story would make a script worthy of George Lucas: the young Jedi Knight who went over to the Dark side of the Force” (Allen, 46-47).

Now, just what might we mean by the dark side? Certainly not the content of Christian doctrine. Perhaps John Allen identifies the dark side with the authoritarian way in which the pre-pope wielded the power of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

Whether liberal or reactionary, it’s my judgment that Benedict XVI offered both church and world a most valuable theological acuity.

Patheos Series on the Soul

Patheos ST 4131 Soul 1 Theologies of the Soul

Patheos ST 4132 Soul 2 Substance Dualism

Patheos ST 4133 Soul 3 Trichotomy

Patheos ST 4134 Soul 4 Materialisms

Patheos ST 4135 Soul 5 Emergent Dualism

Patheos ST 4136 Soul 6 Non-Reductive Physicalism

Patheos ST 4137 Soul 7 Bodily Resurrection

Patheos ST 4138 The Soul of Benedict XVI

Patheos ST 4139 Blessed Mother Olga of Alaska knitted mittens

Patheos ST 4140 Supporting Husbands in Theology

ST 4138. Conclusion

One more thing. Benedict XVI pressed his mind into the service of his heart.

“The true morality of Christianity is love. And love does admittedly run counter to self-seeking—it is an exodus out of oneself, and yet this is precisely the way in which man comes to himself” (Pope Benedict XVI 2007, 99).

What were the final words spoken by Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI at the moment of his passing? “Jesus, ich liebe dich!” Jesus, I love you.

▓

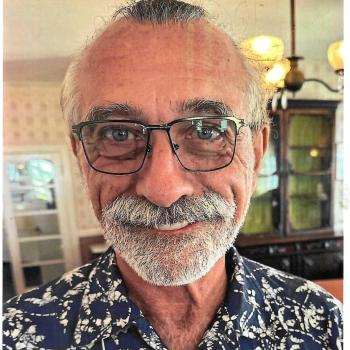

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union. He co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, with Robert John Russell on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. His single volume systematic theology, God—The World’s Future, is now in the 3rd edition. He has also authored God as Trinity plus Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society as well as Sin Boldly: Justifying Faith for Fragile and Broken Souls. See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union. He co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, with Robert John Russell on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. His single volume systematic theology, God—The World’s Future, is now in the 3rd edition. He has also authored God as Trinity plus Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society as well as Sin Boldly: Justifying Faith for Fragile and Broken Souls. See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

He has just published a new 2023 book, The Voice of Public Theology, with ATF Press.

▓

References

Allen, John, 2000. Pope Benedict XVI: A Biography of Joseph Ratzinger. New York: Continuum.

Auer, Johann, and Joseph Ratzinger, 1988. Eschatology: Death and Eternal Life. Washington DC: Catholic University Press.

Benedict XVI, Pope, 2007. Jesus of Nazareth. New York: Doubleday.

Dorflinger, Richard, 2001. “The Policy and Politics of Embryonic Stem Cell Research,” National Catholic Bioethics Quarterly 1:2.

John Paul II, Pope, 1995. Evangelium Vitae. Vatican; https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_25031995_evangelium-vitae.html .

Peters, Ted, 2015. God–The World’s Future: Systematic Theology for a Postmodern Era. Minneapolis: Fortress, 3rd ed.

Peters, Ted; Karen Lebacqz, and Gaymon Bennett, 2008. Sacred Cells? Why Christians Should Support Stem Cell Research. New York: Roman & Littlefield.

Pontifical Academy of Life, 2000. Declaration on the Production and the Scientific and Therapeutic Use of Human Embryonic Stem Cells.” Vatican; https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_academies/acdlife/documents/rc_pa_acdlife_doc_20000824_cellule-staminali_en.html .