Substance Dualism

What do you think about your own soul? Let’s try on some theologies of the soul to see which fits best? In this post we try on ‘substance dualism‘, sometimes called ‘constitutional dualism’.

I wonder if I grew up as a substance dualist but didn’t know it at the time. Did you?

Does our soul go to heaven?

When I was a Sunday School age kid, my image of the soul was that of a spiritual rubber ball that sort of bounced into the body at birth and out again at death. My parents taught me the bedtime prayer:

Now I lay me down to sleep.

I pray the Lord my soul to keep.

If I should die before I wake,

I pray the Lord my soul to take.

When praying, I could imagine me dying and leaving my body in the grave while God snatches my soul and takes it to heaven. It would be as easy for the Lord to catch my ascending soul as it would be for me to catch a baseball. Was I a closet substance dualist?

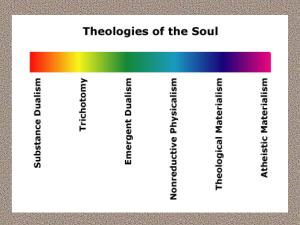

Substance dualism is the first on our list of optional models as you can see on the diagram.

As the label “substance dualism” suggests, we sometimes think of the soul as a spiritual substance. The body is a material substance, while the soul or mind is an immaterial substance. Simple, eh?

At death, like a surgeon removing an appendix, God performs a soulechtomy and removes our soul from our body. Such an adynaton makes it simple, eh?

Well, what are the implications of this model of the soul? (Murphy, 2006).

Substance Dualism

We find substance dualism in the Hindu tradition. According to Hindu substance dualism, the soul incarnates in material bodies repeatedly. One soul. Many bodies.

But we also find substance dualism in Grecco-Hebrew religion too. In the biblical traditions, the soul becomes incarnate for only one lifetime before departing to eternity.

The usual term for soul or self in Sanskrit, ātman., This word, atman, likely has etymological connections with the Sanskrit word for breath, which is often expressed as prāṇa. This double reference to soul and breath is similarly found in the biblical Hebrew, nefesh and ruach. So too the Greek psyche (ψυχή), which may also be rendered “breath-soul.” This term is based upon the verb ψυχω “I blow.” When we breathe, we’re alive. When we stop breathing, we’re dead. Simple, eh?

BTW, don’t confuse soul (ψυχή) with spirit (π√ευμα), which also alludes to breath or wind or air. The soul is our essence as an individual. Our spirit unites us with others and with God.

The Soul as the Whole Person

The association of life or life-force with ‘soul’ does not necessarily imply substance dualism. For a body to be alive, it needs more than material make-up. It needs air or breath to become animated.

Let’s look a bit more closely at these ancient words. Terms such as psyche, ātman, and nefesh may refer to body-mind-life. That is, the whole individual. The early Hebrews viewed the nefesh as a unitary being. A human person does not have nefesh. Rather, he or she or they are nefesh.

Correspondingly, in the New Testament, psyche may also refer to the whole person (Matt. 11:29) or the physical life of a person (Matt. 6:25). Here’s the point: the term soul need not be attached to substance dualism. It could refer to a person as a whole, as body, soul, and spirit.

Modern Christian Substance Dualism

“Scriptures clearly teach that man has a physical and non-physical aspect,” declares Rey Renoso. On his blog site, Bible Archive, Renoso calls this position, dichotomy. But, we might ask: does dichotomy require substance dualism? Just what is substance dualism, anyhow?

In an earlier post on the Immortal Soul, we reported that the French philosopher, René Descartes (1596-1650), formulated what we now know as substance dualism.

Recall that Descartes disconnected our soul—our subjective mind—from the physical or material world, from the objects we perceive. This division has been nicknamed the “subject-object split.” Accordingly, our mind is a spiritual substance. Objects we perceive are made of a material substance. Unless they’re imaginary, of course.

In short, our mind is a “thinking thing” (res cogitans) or immaterial substance. Our body is a “thing that exists” in time and space (res extensa). This combo is unique to humans. Animals, thought Descartes, have a body but not a soul.

It is our thinking soul that connects us with God.

“By the name God I understand a substance that is infinite [eternal, immutable], independent, all-knowing, all-powerful, and by which I myself and everything else, if anything else does exist, have been created. Now all these characteristics are such that the more diligently I attend to them, the less do they appear capable of proceeding from me alone; hence, from what has been already said, we must conclude that God necessarily exists” (René Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy, III).

The upshot is that the ol’ debate between Plato and Aristotle on the soul got revived. Today, we must re-think all this in light of the no-soul position of materialism. Is your head spinning like mine is?

God-Consciousness in Liberal Protestantism

Back to history. By the turn to the 19th century, the Latin Christian tree grew a new branch called “liberal Protestantism” or “theological liberalism.” Following Descartes—and Immanuel Kant too—the liberal Protestants located the human relationship with God in our subjectivity. The father of liberal Protestantism, Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834), bequeathed to his descendants the connection between religion and feeling (das Gefühl).

“The sum total of religion is to feel that, in its highest unity, all that moves us in feeling is one; to feel that aught single and particular is only possible by means of this unity; to feel, that is to say, that our being and living is a being and living in and through God” (Schleiermacher, 1958, 49-50).

Without adopting the metaphysics of substance dualism, Schleiermacher still divided sharply between subjective feeling and objective perception. Our consciousness of God belongs in the former, in subjective feeling.

According to today’s liberal Protestant, our relationship with God is mediated by feeling that takes place in our subjective consciousness. God works in the heart, mind, and soul to transform our subjectivity. God does not work in the objective bodily world to reveal the divine self or to perform miracles or such.

Liberal Protestant theology is one fruit on the branch of the Christian tree fertilized by the influence of substance dualism.

There is such a farraginous variety of beliefs touted by today’s progressive Christians that it’s hard to pin down a concensus. Just flag this: liberal Protestantism was born when the Enlightenment became pregnant with Cartesian substance dualism.

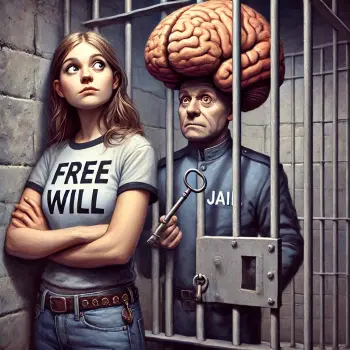

Substance Dualism vs Reductive Materialism

In our own 21st century, Descartes’ substance dualism has been widely discarded right along with the obsolete telephone booth. Today’s philosophers prefer to embrace materialism, not substance dualism. Only material reality is real, accordingly. The mind is reducible to neuronal firings in our brain, accordingly. Let’s get rid of spiritual substances and immortal souls! When the brain dies, the ‘I’ dies with it! That’s all there is! Get over it! Thus speaketh our materialist friends.

Christian theologians are trying to adapt to the new materialism. Instead of a soulechtomy (an extraction of a soul substance from a bodily substance), Christian theologians affirm a divine act wherein God raises the dead—the whole person: body, soul, and spirit–in bodily form. Resurrection of the body replaces immortality of the soul. Well, most but not all Christian theologians affirm resurrection of the body.

Body vs Soul? Flesh vs Spirit?

It’s important for the Christian to distinguish between two distinctions. One is body vs soul. This is different from flesh vs spirit. Flesh in the New Testament is a force, not a substance. Flesh is something like rot. Flesh contaminates and dirties our spiritual relationship with God. Flesh tempts us to sin.

Here’s the important point: obstructions blocking our pursuit of godliness are posed by the flesh, not the body.

“Now the works of the flesh (sarx) are obvious: fornication, impurity, licentiousness, idolatry, sorcery, enmities, strife, jealousy, anger, quarrels, dissensions, factions, envy, drunkenness, carousing, and things like these. I am warning you, as I warned you before: those who do such things will not inherit the kingdom of God. By contrast, the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness.” (Galatians 5:19-22).

Although St. Paul here does not actually say this is a struggle between body and soul, some in the Christian tradition have read it this way. When the struggle between flesh and spirit becomes translated into a dualism of body and mind, we get modern phrases such as “mind over matter.”

The idea of an individual soul as a non-physical substance seems to fit with some of our everyday experiences. I emphasize seems to fit our experience. What we experience is a battle between what we think in our soul and what our body demands of us. When our rational mind says it’s time to lose weight, we may experience a struggle when walking the aisles of the supermarket or reading a restaurant menu. It takes mental work to forfend our diet from the temptation to buy and devour all that appears tasty. It is not unreasonable to explain this experience as a battle between flesh and spirit, between our physical bodies and our spiritual souls.

But a more careful reading of the New Testament will show that the temptations of the flesh leading us toward sin take place in the soul, not the body. We dare not blame our body for what the soul does.

Where have we been? Where are we going?

In a previous Patheos series on the afterlife, we took a close look at both the immortal soul and reincarnation. Here in this series on Theologies of the Soul, we’re ready to move on to number 3 on our list: the Trichotomy of body, soul, and spirit.

Patheos ST 4131 Soul 1 Theologies of the Soul

Patheos ST 4132 Soul 2 Substance Dualism

Patheos ST 4133 Soul 3 Trichotomy

Patheos ST 4134 Soul 4 Materialisms

Patheos ST 4135 Soul 5 Emergent Dualism

Patheos ST 4136 Soul 6 Non-Reductive Physicalism

Patheos ST 4137 Soul 7 Bodily Resurrection

Patheos ST 4138 The Soul of Benedict XVI

Patheos ST 4139 Blessed Mother Olga of Alaska knitted mittens

Patheos ST 4140 Supporting Husbands in Theology

ST 432. Soul 2. Conclusion

Biblical terms such as body, flesh, soul, spirit, and such aptly describe factors in our human struggle to live a disciplined and godly life. But we need not think of them as substances.

That we have a soul at all is due to our engagement with God in such a way that a spiritual receptivity opens within our personhood. This spiritual receptivity conditions the formation of our selfhood. Over time it defines who each of us is as a particular person. Your soul and my soul are each unique, even if we share them spiritually with one another and with God.

▓

For Patheos, Ted Peters posts articles and notices in the field of Public Theology. He is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union. He co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, with Robert John Russell on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. His single volume systematic theology, God—The World’s Future, is now in the 3rd edition. He has also authored God as Trinity plus Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society as well as Sin Boldly: Justifying Faith for Fragile and Broken Souls. See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Watch for his 2023 book, The Voice of Public Theology, published by ATF Press.

▓

References

Murphy, N. (2006). Bodies and Souls, or Spirited Bodies? Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press ISBN 978-0-521-67676-2 pb.

Peters, T. (2018). Models of the Soul: Comparing Concepts. https://tedstimelytake.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/models_of_the_soul.pdf: TedsTimelyTake.

Schleiermacher, F. (1958). On Religion. New York: Harper.