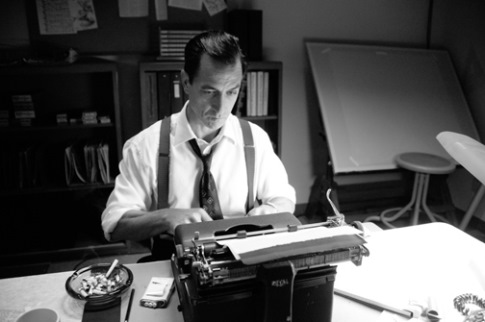

In the 2005 George Clooney-directed black and white film, Good Night and Good Luck, a bully emerges and exploits fear to gain dominance and one man finds the courage to stand up to him. The recounts the journalistic confrontation of Edward R. Murrow against Senator Joseph McCarthy and his witch hunt for Communists in the 1950s. (You can rent or purchase the film on Amazon’s streaming video service.)

The script, written by Clooney and Grant Heslov, is spare and elegant. It draws in real footage of McCarthy and the Senate hearings from the era. Clooney has said that he chose to let McCarthy play himself because “if you had an actor actually do an exact impersonation of Joe McCarthy, every critic in the country would say that we’re making him too much of a buffoon and too arch. You wouldn’t really believe that someone could reach that kind of power acting the way he did.”

The film effectively recreates the atmosphere of fear created by McCarthy in the 1950s. Because the Senator would attack and delegitimize anyone who stood up to him, his power continued unchecked for several years until his censure in 1954. Murrow, as one of the few willing to stand up to him, might seem to most of us to be outside the realm of normal humanity. But what makes this film so effective and compelling is the way David Strathairn portrays the humanity of Murrow, the camera zooming in on his face, sweat visibly beading on his brow, as he nervously takes a drag on a cigarette and quips to a colleague, “It occurs to me we might not get away with this one.”

There was real risk in doing what Murrow did. People got ruined doing things like Murrow did. There was no doubt McCarthy would attempt to destroy him for doing it. The camera and Strathairn do not shy away from showing us his nervy fear. He first challenges the military’s treatment of Milo Radulovich, who was told to denounce his father because the elder read a Serbian newspaper and who responded he would not do so, adding that if he renounced his parent, “I see a chain reaction that has no end to anybody.” He moved on to challenge the lack of due process in the accusations of working for the Communists that were leveled against Annie Lee Moss, a Pentagon clerk. McCarthy responded predictably and responded by making a case that Murrow himself was a Communist. The intimidation intent was clear. But Murrow came back and rebutted and fact-checked McCarthy’s charges. Because of the trust in Murrow, his news investigation of McCarthy became an influential factor in the Senator’s downfall. Ultimately, truth prevailed.

Good Night and Good Luck (the famous phrase with which Murrow signed off after each broadcast) is a hopeful film, fiercely defending the value of the free press to confront unchecked leaders and provide them with accountability. But it also honestly portrays the fear we experience when we stand up to such leaders, particularly when they seem all-powerful and when they have destroyed other people who stood up to them. In the film, Murrow wraps up an anti-McCarthy report and fixes his laser gaze on a nearby rotary phone, waiting with trepidation for it to ring. Later, the CBS staff gathers at a bar and has drinks until the wee hours of the morning, when the early editions of the newspaper come out. In an era before the internet, there was not a good way to get a read on the national consensus until the newspapers published. The news staff sends a colleague to bring the papers and as they wait, a nervous silence descends on the room, lingering like pervasive clouds of cigarette smoke. If we look at that kind of power and intimidation and feel tempted to shirk our duty, it is helpful to know that even our heroes felt fear. They didn’t know what the outcome would be. But they still did their duty.

Another of the film’s strengths is that it portrays vigorous debate among the members of the journalistic team at CBS as to precisely what journalists are called to do. Must they always provide two sides of every argument with equal weight? Is it wrong to have a journalistic point of view? Should journalists keep pressing, being a burr in the side of leaders or should they let them self-destruct when they get off course? (I’m curious about your thoughts on these! Drop a comment below!)

The film also offers important cautions and challenges to the ad-driven movement toward entertainment rather than informative hard news. It intersperses real ads from the era throughout the film. We see Murrow having to conduct vacuous celebrity interviews in order to pay the bills–not his favorite task but one he is willing to do so that he can continue doing hard news. And the film begins and ends with a speech Murrow gave to colleagues at the Radio Television Digital News Association in 1958, in which he issued stern warnings about the way a focus on entertainment and ad dollars could lead television networks far away from their lofty vocation (awfully prophetic!). Although only key portions of Murrow’s speech are included in the film, you can read the whole thing here.