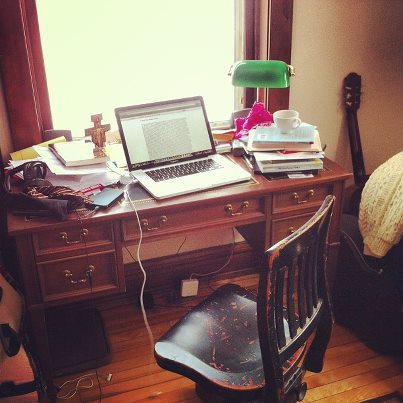

I was destined for the collar. Everyone seemed to see that, and believe it, too. Fr. O’Malley, the priest who converted my father and baptized me, would take me out for a steak dinner sometimes. He’d always say, “When you’re a priest, you can eat steak everyday.” That stuck. I love to eat. I felt obligated to say that I wanted to be a priest when I grew up. Not sure why, but I knew there was no firefighting in my future. I was a devout and precise altar server until I took over music ministry and liturgy planning from Jr. High into college. In high school there were vocation retreats and visits from the diocesan vocation director. I’d lived my entire life in rectories and church offices. I knew and loved and despised dozens of priests. I understood the vocation as well as any high school student could. Fr. Sam, a wonderful mentor to me, offered to pay for my college tuition—the implicit agreement was that I’d be ordained a member of the Society of the Precious Blood. I couldn’t do it. It wasn’t the fear of becoming a priest someday: that I could deal with, I’d been dealing with it my entire life. It had more to do with not wanting to let Fr. Sam down, a man I truly loved. As cocksure and bright as I seemed on the outside, I had no idea what I could do in college. No internal sense of competence or confidence. Always guessing. No one cared to tell me that I was over-preparing with my debate regimen and Georgetown didn’t mean anything to me then. After showing promise in competitive debate, a State scholarship and some philanthropic money sent me to Waco, Texas for two weeks. Baylor Debate Camp. Besides eating in the cafeteria of Hardin Simmons University before a playoff football game, I’d never seen a college campus before and I had no idea, really, what it would be like there. My roommate was Jewish. We were enrolled in the exclusive, “expert” tier. I was certainly no novice, but I probably belonged in the intermediate group. I figured I’d never get to do this again, so I’d better see what the best people were doing. It was the summer before my junior year. The year earlier I’d beaten the best debater in our district, a senior from Ballinger, Texas, for the final spot at regionals. She and I had debated in my very first tournament the year before that, when I was a freshman. She dusted me in the semi-finals. But I was in over my head at regionals. I needed better content and polish. Even my proud, paraplegic coach admitted that I needed outside help: debate was new at little Brady High School. This was a first for him, too. He had played and coached basketball before his accident and won state titles. Now he was my coach and we were going to win trophies and medals and go to state together. So I needed to get better. Lincoln Douglas debate is a one-on-one combat over value propositions. The foundation was always philosophy, or some legal derivative. I needed to learn about philosophy and get more training in the rhetorical techniques being used by the big-league, national circuit debaters. There were kids from all over the country. Baylor University. Walking the campus was something out a dream or a movie I’d never had the data to imagine or process. It felt free and frightening and I knew I would have to go to college someday to spend more time at such an enchanting place. This was better than church. I’d never heard of a coffee shop before, but I did have a taste for coffee: prayer meetings always served coffee and Dad always let me drink it, with milk and sugar. “Common Grounds” was dark and, on that night, packed with debate nerds. I had money, I got an envelope with $215 dollars in it, for spending. I had no idea what to do with that much money in such little time, but I felt obliged to spend it there, at Baylor, not to try and save it and take it home with me like I would usually do. Coffee was expensive. I learned the ritual of ordering and waiting and where the bar was with the napkins and stirring sticks and salt-shaker things to add flavors to the coffee. Cocoa. Then conversation. The dance. Sparring. I befriended a group of novice-level debaters who thought I was more important that I really was, and I acted like it. The first morning opened with a welcome, followed by a lecture from a professor in the communications department. He was wearing a blue Oxford shirt with huge, sweaty pit stains. He spoke passionately, with amazing and animated words and phrases and magic. His rhetoric was something I’d read of, but never heard before in person. I starting to wonder if I could do that. I also recalled the great preachers I’d heard and began to realize that my father was one of them. He had pathos. Then came the other lectures, from our tutors and guest philosophy and law professors. We learned the basics of ethical theories and political philosophy. The lectures were brilliant and exciting: I took notes in a way I’d never done before and wouldn’t repeat for a long time thereafter. I kept and treasured those notes for many years. Two blue legal pads. At first I didn’t dare to say a word when the lecturer would pose a question, but I always rehearsed an answer in my head. I was right! The big shots never answered the easy questions, they waited to ask questions of their own. I started thinking of questions to ask. Then objections. It just kept going. Soon I was tangling with the big shots at the coffee shop. We all received a small paperback library of primary philosophical texts, the classics from Plato to Rawls, each with an introduction and tips on how to convert the ideas into debate fuel. I read them every night till I had to start preparing my debate cases for practice rounds and the tournament. I did well. Before leaving I went to the college bookstore and bought four books: the Penguin Dictionary of Philosophy, the Oxford Companion to Mill, Rousseau’s Social Contract, and a compendium on political philosophy. My money was all spent and my mom picked me up. We listened to Cat Stevens on the way home. I felt like she understood that I left that place a different man, headed in, perhaps, a different direction. My doctoral advisor was shocked at my upbringing and my ignorance of academic pedigree and decorum and who’s who and where’s where and whatnot. My first year we rode the bus together—he hated to fly—to Chicago for a regional conference. On the second day we went to the University of Chicago, to see the campus, walk the halls, and witness the Lab School, founded by John Dewey, the misfortunate patron saint of Philosophy of Education. It was a damp, grey day. The gothic architecture stood with dignity and self-importance and the halls seemed electric with ideas and smarts. I wept, reverently. I’d at least heard of Georgetown, but Chicago was just a big city to me. I never knew such a place existed. My advisor didn’t help. “You could have gone here, Sam, I’m sure of it; maybe someday you’ll teach here. Wouldn’t that be something? Let’s go find a bookstore.” We made our way to a perfect used bookstore where I bought a rare early edition of William James’ Human Immortality for five dollars. I read it on the train ride back to our hotel. The book was engrossing and reading it afforded me the privacy to try and process some of what I’d just experienced. Now I was sure of it: I would become a professor. I would work retroactively to redeem myself and make-up for lost time and opportunity. I watched the last lecture of Fr. James Schall about a month ago. The Final Gladness. This time I understood exactly what Georgetown was, but I also had lost much of my former romance with the academy. I was becoming cynical and unhappy. Insecure, too. The light in my eyes was dying. I was losing my vocation, or something like that. Doubting it, like I’d always doubted , and ultimately rejected, the idea that I was born to wear a Roman collar. Schall’s somewhat boringly erudite, but rich and soothing, lecture showed me a man who spoke as a professor first and foremost. A person professing. Was that it? Was that the priest I was destined to be? Might I be graced with the chance to be a husband and a father and a “professor”—a secular priest of sorts? A man like my father? I don’t know what a vocation is. Even after all these years and diocesan posters and pressure I don’t understand it one bit. I understand its etymology, vocare: a calling, but that’s about it. This thing we call “vocation” is, for me, still a total mystery. The call is as absent to me as the One who calls. I still don’t know what I want to do or who I want to be when I grow up. Maybe a writer? A musician? I am a professor now, today, even though it is out of fashion for professors to profess these days. And when will I be “grown up”? When I’m dead? These are sentimental and silly questions, juvenile and flighty aspirations, but they are the roots and spirit of the stories I’ve recalled and shared nonetheless. A cubicle is a just a workplace. Like the one I sit in now. I have a very nice desk, a writing desk. Simple, but simply perfect for the time being.