I appreciate the point John Fea is making in this post on “The Willow Creek Mess.” It’s well-observed and well-taken.

In short, he was discussing a prominent figure from American history in a recent summer seminar for a group of grade-school history teachers. Because that prominent figure was a famous preacher and evangelist, the audience had a dismal expectation for how the man’s story would end, prompting one of the teachers to raise her hand with a question:

“So what happened with this guy? As I hear you talk I am expecting some kind of scandal or moral indiscretion. How did [he] fall?” This teacher seemed surprised that [the preacher] never got caught-up in some kind of sex scandal. She assumed that the [preacher’s] story ended badly. …

I thought about this teacher’s question as I read more about Bill Hybels and his moral indiscretions while serving as pastor of Willow Creek Community Church. She may have meant her question to be snarky or cynical, but I did not take it this way. It seemed like she had just come to expect this kind of thing from popular and powerful evangelical preachers.

This is where we are in 2018. If you start telling a story about a popular white evangelical preacher, those hearing that story will expect it to end the same way as so many of these stories do.

I think Fea is right about that teacher’s question. She wasn’t intending to be cynical in a hostile manner, but everything she’d heard and learned about prominent evangelical preachers had taught her a pattern that she quite reasonably expected to be reflected in the life of this earlier figure. Whether this teacher was 25 or 65, she had few examples in her lifetime of famous, popular, powerful white evangelical leaders whose story didn’t end in some kind of “fall” into disgrace due to some wretched scandal involving either sex or money.

Billy Graham, I guess — if we don’t consider the ugly racism of his son or his father-in-law as “scandals” that should count against him. (And if we forgive him for his obsequious assent to Nixon’s horrible mutterings about “the Jews.”) But the handful of exceptions to this pattern seems dwarfed by the seemingly endless parade of examples that reinforce it: Jim Bakker, Jimmy Swaggart, Benny Hinn, Robert Tilton, Tony Alamo, Ted Haggard, Paige Patterson, Paul Pressler, Bill Gothard, Doug Phillips, Richard Land, C.J. Mahaney, Paul Crouch, Mark Driscoll, Dan Johnson, Andy Savage, Frank Page, Bill Hybels … the list goes on and on.

It ain’t pretty.

So I’m right there with John Fea lamenting the devastating damage this long succession of scandals has wrought to the church and to Christian witness in this world.

But here’s the thing: that historical figure Fea was discussing may not have had a sex or money scandal, but he did something far, far worse. Here’s the unedited version of that first paragraph quoted above:

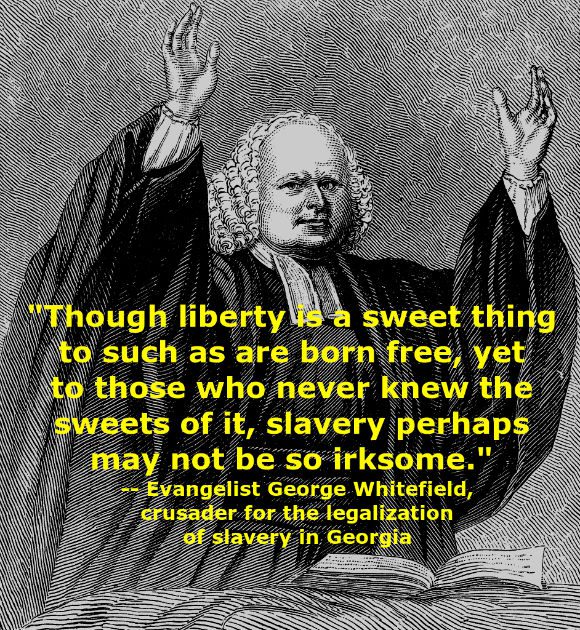

At one point in the lecture, an elementary-school social studies teacher who had never heard of Whitefield raised her hand and asked, “So what happened with this guy? As I hear you talk I am expecting some kind of scandal or moral indiscretion. How did Whitefield fall?” This teacher seemed surprised that Whitefield never got caught-up in some kind of sex scandal. She assumed that the Whitefield story ended badly. We stopped and talked about Whitefield’s self-promotion, his ownership of slaves, and the way he divided local congregations, but as far as I know there was never an Elmer Gantry or Jimmy Swaggart moment in Whitefield’s life.

Whitefield is George Whitefield — itinerant revivalist of the Great Awakening and one of the most famous international celebrities of the 1700s. He was a spellbinding orator who enthralled massive crowds in a time when microphones and speakers didn’t yet exist. He preached thousands of sermons on both sides of the Atlantic before crowds that have been estimated to total as much as 10 million people (at a time when the total population of the American colonies was less than 3 million). Whitefield’s influence on American popular religion, and formal religion, and culture more broadly, can hardly be overstated.

But while Whitefield never fell into disgrace and scandal during his lifetime — never had “an Elmer Gantry or Jimmy Swaggart moment” — his legacy has been far more disgraceful and enduringly harmful than any of those scandalized wretches we listed above.

Because it wasn’t simply that George Whitefield was a slave-owner. He was an advocate for legalizing slavery and for building the economy of the Southern colonies firmly atop the monstrous system of plantation slavery.

Whitefield operated a famous orphanage in the colony of Georgia. (It’s still there, sort of, now existing as a boarding school for boys called Bethesda Academy.) The orphanage was supported by the large plantation Whitefield owned in Georgia, but that plantation was losing money, and Whitefield was sure he knew why: because slavery was illegal in the colony of Georgia.

No, really, it’s true. The new colony of Georgia was officially chartered in 1732 and soon thereafter wrote itself a constitution that prohibited the buying and selling of human beings, the lifelong theft of their labor, their abuse, rape, and torture.

We don’t learn this in school. We almost un-learn it in school, acquiring a kind of inability to absorb such a thing because it doesn’t fit with the myth-making narratives preferred by either North or South. But it’s true: slavery was not always legal in Georgia.

In 1740, when Whitefield began construction of his orphanage in the colony of Georgia, slavery was illegal there. Slavery was perfectly legal in New York City, in Philadelphia, in Boston — but not in Savannah. Up north, in New Haven, Jonathan Edwards had already purchased three people, enslaving them in his New England parsonage. (Their names — or, rather, the names they were assigned and allowed — were Joseph, Lee, and Venus.)

But in 1740 slavery was illegal in the colony of Georgia. As it always had been. Whitefield wanted to change that, because he was sure that abducting a bunch of God’s children and violently forcing them to work without pay, forever, would make his plantation profitable and his orphanage viable (spoiler alert: it did not).

And so Whitefield used all the power of his celebrity and his reputation as a pious leader to lobby the crown and the trustees of the colony to change its constitution: “Hot countries cannot be cultivated without negroes,” he wrote in one letter, laying out his case. “What a flourishing country might Georgia have been, had the use of them been permitted years ago? How many white people have been destroyed for want of them, and how many thousands of pounds spent to no purpose at all?”

Whitefield’s efforts paid off and, to his great delight, slavery was legalized in the colony of Georgia by a royal decree in 1751.

Might slavery eventually have become legal in Georgia without the big push from George Whitefield? Maybe. Probably. Perhaps it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom, etc.

The simple fact is that George Whitefield was instrumental in the expansion and the industrialization of chattel slavery in the Americas. That’s far, far worse than anything that Ted Haggard or Jimmy Swaggart got caught doing in a motel room. It’s far, far worse and farther-reaching in its destructiveness than anything that any of those scandalized, “fallen” preachers listed above ever did.

Acknowledging that does not, in any way, minimize or dismiss the real harm wrought by many of those predatory preachers. Their sins are many and they are real. They earned their disgrace, even if their various misdeeds and predations did not rise to the nation-shaping monstrosity of Whitefield’s role in expanding plantation slavery.

And there’s a real sense in which those disgraced preachers, too, are a part of George Whitefield’s legacy. They are a product of the kind of white evangelical Christianity he preached and popularized. They are an inevitable result of his white theology. When you create and disseminate an otherworldly, obtuse form of religion that is incapable of opposing the starkest forms of injustice and oppression, then you’re bound to wind up with the kind of religion that elevates “leaders” like these. A bad tree cannot be expected to bear better fruit.

I share Dr. Fea’s sadness at the popular perception today that the story of any white evangelical preacher is bound to end in scandal and disgrace. I share his sadness that this perception is largely accurate. But changing that means candidly facing up to the roots of white evangelical Christianity in the otherworldly, unjust theology of slaveowners and slavery advocates.

In a related post on “The Willow Creek Mess,” Scot McKnight suggests that the megachurch will be unable to move forward — will be undeserving of moving forward — until it grapples honestly with the failure of its leadership and the way that has misshaped the current state of that community: “Willow will never be the old Willow. It can become a different Willow, but it will never be the same.”

The same is true for white evangelicalism as a whole. It needs to reckon with the way its theology, its hermeneutics, its piety, devotion, practice, worship, and ministry have all been pervasively formed by its birth and growth alongside of slavery. It’s possible that it can move forward by becoming something new and different, but if it tries to remain the same, old white evangelicalism, then it will never change its pattern. And the parade of scandal and disgrace will never end.