David Swartz looks at “Innocent Readings of Evangelical History” and finds them guilty.

On one level, this is an essay expressing the academic concerns of a historian warning about the distortions that can arise from seeking “a usable history.”

But on another level this is a fiery sermon calling for repentance, lamentation, fasting, sackcloth and ashes. Swartz doesn’t cite a particular biblical text for this sermon, but Matthew 23:29-35 is too apt not to quote it here:

Woe to you, white evangelicals, hypocrites! For you build the tombs of the prophets and decorate the graves of the righteous, and you say, “If we had lived in the days of our ancestors, we would not have taken part with them in shedding the blood of the prophets.”

Thus you testify against yourselves that you are descendants of those who murdered the prophets.

Fill up, then, the measure of your ancestors. You snakes, you brood of vipers! How can you escape punishment?

Therefore I send you prophets, sages, and scribes, some of whom you will kill and crucify, and some you will flog in your churches and pursue from town to town, so that upon you may come all the righteous blood shed on earth.

Swartz doesn’t employ the kind of invective Jesus uses in that Gospel passage, opting instead for a plain-spoken, matter of fact tone: “rotten to its core” or “For every [white] evangelical abolitionist from the 19th Century, there were a hundred slaveholders and thousands who stood silently by.” But he closely parallels the argument I think Jesus is making there in Matthew 23, which is not so much a condemnation of hypocrisy as it is an identification of cause and effect.

The point here is not the self-flattering duplicity of “If we lived in the days of our ancestors, we would not have taken part with them in shedding blood.” It’s the danger that the arrogance of this selectively reassuring view of the past makes us far, far more likely to repeat the same bloody behavior in our own time. We kill and flog and pursue the prophets of our age in part because we have embraced the unearned delusion of identifying ourselves with the prophets and the heroic exceptions of the past.

Here’s Swartz:

The inspirational stories that moderate evangelical institutions tell about themselves aren’t helping. Many marshal a usable history to convince themselves that their tradition is not rotten at the core. Former George W. Bush speechwriter Michael Gerson, for example, appeals to historical examples of 19th-century abolitionists and suffragettes. Wheaton College cites Jonathan Blanchard, its first president who made campus a safe stop on the Underground Railroad during the Civil War. Wesleyans, mining Donald Dayton’s Discovering an Evangelical Heritage …, point out that Methodists helped launch the women’s suffrage movement, that missionary E. Stanley Jones integrated evangelistic crusades — soon followed by Billy Graham.

To square this impressive evangelical past with the sordid present, they use the narrative device of historical declension. Evangelicalism, moderates maintain, has declined from its former enlightened stances on issues of social justice. Billy Graham’s legacy has been coopted by his son Franklin. James Dobson, the apolitical psychologist who began tasting the delights of political power, became a culture warrior. Evangelicals who never would have supported Donald Trump in the 1970s voted for him en masse in 2016 and 2020. If contemporary evangelicals would only know their enlightened history — and stay true to it — they would be more willing to say that Black lives matter.

The problem is that these narrations cherry-pick unrepresentative voices from the past. Abolitionists never really represented the mainstream of [white] evangelicalism. There were always more slaveholders than Grimké sisters. Leaders who want to minimize (or distract from) evangelical support for Trump narrate the movement as more cosmopolitan than it has actually been. They peddle what Cuban-American theologian Justo González calls “innocent readings of history.” They minimize the bad, emphasize the good, and ignore how moderation often perpetuates injustice. They portray their own history as more innocent than it actually was.

Swartz refers there to the Grimké sisters (Sarah Grimké and Angelina Grimké Weld), who should be more widely known and celebrated because their work and their witness remains, as Swartz says, inspirational. I first learned of them in that book of Donald Dayton’s that Swartz also mentions, Discovering an Evangelical Heritage, which I first read as another source of “inspiration.”

Dayton’s project in that book was not to present an “innocent” history or even, really, a “usable” one. The alternative “heritage” Dayton sketches and celebrates is something he presents as exactly that — an alternative, an exceptional, prophetic deviation from the norm and from the majority that he presents as evidence that something other than our current norm was once and still might be possible. Dayton’s project wasn’t a defensive, exculpatory claim of #NotAllEvangelicals. And it wasn’t some attempt to show that most evangelicals were once advocates for justice. He was, more humbly, simply trying to demonstrate that it was possible to be an evangelical without reflexively condemning and opposing every attempt to bring about greater justice in this world.

That, at least, is how Dayton’s book was first presented to me by those mentors of mine who were themselves the subject of a similar-ish book written by David Swartz. Ron and Tony and Jim urged all of their young followers to read Discovering an Evangelical Heritage in the hopes that we would be inspired to help create a different kind of evangelical heritage than the one we’d inherited from the majority of our tradition.

Alas, the very same history in Dayton’s book that initially struck me as inspirational later came to seem depressing. The long list of exceptional heroes he profiles were, indeed, people who were inspired by their devout evangelical faith to commit their lives to the work of justice. And they were, therefore, in nearly every case, people who either gradually or abruptly ceased to be evangelicals.

Here’s what I wrote about Dayton’s book in a footnote to this post six years ago:

We still play this game — highlighting the exceptional few from the past as the true representatives of our history and pretending they were not, in fact, exceptional, and that they were not, in their time, vehemently condemned and rejected by their fellow white evangelical Christians.

Let me again recommend Donald W. Dayton’s wonderful book Discovering an Evangelical Heritage, which spotlights the honorable history of many such exceptional Christian activists — the few white evangelical voices of their time who were not wrong about slavery. Many of those stories are inspiring, but I don’t think they add up to “an evangelical heritage” as much as to a frustrating account of a road not taken, an alternate path repeatedly offered to and rejected by the majority of 19th-century white evangelicals. Many of the abolitionists Dayton profiles began as devout evangelicals but — with equal parts jumping and pushing — wound up far outside the evangelical fold, as Quakers or theological liberals or various sorts of vaguely Emersonian post-Christians.

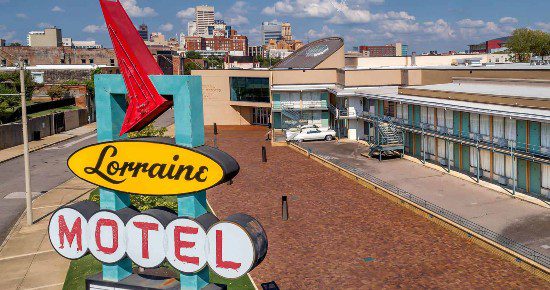

Yes, the story of the “Lane rebellion” and the founding of Oberlin College by a bunch of abolitionist evangelicals is a terrific slice of history, but that history also has to include the way Oberlin was quickly ostracized and “farewelled” out of fellowship with the rest of white evangelicalism, pushed off from its origins to become, well, Oberlin College. The white evangelical abolitionist Jonathan Blanchard was also instrumental in the founding of what is now a well-regarded midwestern school, but today Wheaton College remains staunchly evangelical in all the ways that Oberlin is not precisely because it sloughed off every trace of Blanchardism except for his belief in temperance.

My point being that when our attempt to say #NotAllWhiteEvangelicals were wrong about slavery leads us to compiling a list of “evangelicals” that has to include people like Theodore Dwight Weld and Angelina Grimké, I think the strain of that exercise begins to show.

Those exceptional few white evangelicals who were on the right side of the abominable matter of slavery quickly found themselves to be on the wrong side of white evangelicalism. The same was true throughout Reconstruction and Redemption, and again in the Second Reconstruction of the Civil Rights Movement and in the Second Redemption of, well, roughly my lifetime.

And what all that adds up to, Swartz suggests, is that my diagnosis of six years ago is insufficiently radical. It’s not enough, he argues, to simply think of this shameful past as “a frustrating account of a road not taken, an alternate path repeatedly offered to and rejected by the majority of … white evangelicals.” That’s too limited, Swartz argues:

Innocent narratives allow evangelicals to blame particular historic choices for their sins and avoid deeper questions of identity. … But it’s worth considering what caused these choices in the first place. Perhaps white evangelicals’ recalcitrance on race, perhaps their inadequate definition of racism as a white person being mean to a Black person was less the result of a historical choice than a problem with evangelical identity itself. … In short, blaming individuals of the past rather than collective traits is an innocent reading of history that prevents evangelicals from truly pursuing racial justice. Indeed, the evangelical toolkit — especially the individualistic way it explains the world — seems designed to do precisely the opposite: to maintain unjust systems.

I think that’s compelling and convincing. What Swartz calls “the evangelical toolkit” — its defining, identity-shaping characteristics — seem “designed … to maintain unjust systems.” And because that is what this identity is designed to do, that is what it will do. That is its function, its purpose, its DNA, its reason for being.

The word “designed” there raises hackles for some folks, who see it as an accusation of some deliberate plot drafted and implemented by a nefarious cabal of architects. (That’s perhaps especially true for white evangelicals who have been reading quasi-creationist arguments about “intelligent design” or overconfident pop-apologetics assertions that insist creation implies a creator.) But that misunderstands — and reverses — what Swartz is saying. It tries to foist evangelicalism’s oppressive identity and overwhelming association with injustice back into that individualistic realm of “particular historic choices.” And that’s precisely what he’s denying here.

The white evangelical “toolkit” is designed to maintain unjust systems because it arose, evolved, and adapted in order to do just that. The English-speaking “Bible Christianity” of white evangelicalism was born at the same time and in the same places as the Transatlantic slave trade. They grew up as siblings under the same roof, influencing and shaping and defining one another. (Hence my Twitter-handle joke about the “1611 Project.”)

Swartz references Jemar Tisby’s “excruciating” The Color of Compromise, which offers a break-neck historical survey of that long, relentless evolution. We can try to read that history as a string of bad choices made by bad individuals, but it’s difficult to sustain such a reading of the dismaying trajectory of the facts Tisby assembles. Yes, time and again, individuals encountered the choice between preserving or opposing the “unjust systems” in which they found themselves pervasively entangled. And yes, their choices might have changed that trajectory, changed history, changed the world. As the abolitionist Albert Barnes said, “There is no power outside of the church that could sustain slavery an hour of it were not sustained within it.”

But those individuals were too invested in those systems, and those systems were too invested in them, for any but the most exceptional of them to see any other choice as really possible. That’s what “system” and “systemic” means. “For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places.”

White evangelicalism led white evangelicals to choose “to maintain unjust systems” because that is what white evangelicalism, from its origin as a species, had evolved to do. White evangelicalism and “unjust systems” have been so inextricably intertwined that I’m not sure it’s possible, four centuries on, to cut away the latter and still have anything left of the former that is in any way recognizable.

But that is the task before us. Anything less entails filling up the measure of our ancestors.

See earlier:

- We would have taken part with them

- When after all it was you and me

- Try not to be the Bad Guy in the story