Evangelicals are woke. In the wake of the killings of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Ahmaud Arbery in South Carolina, Breonna Taylor in Louisville, and others around the country, many evangelicals, even white ones, have become more willing to say the words “black lives matter.” They’re quoting Martin Luther King, Jr., W. E. B. DuBois, and Ibram Kendi. Large swaths of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship have embraced the discourse of #blacklivesmatter. Productive engagement with critical race theory has grown strong even in the more conservative campus ministry Cru. At Wheaton College, philosophy professor Nathan Cartagena, who has become an interpreter of critical race theory to Christianity Today-oriented evangelicals, says that CRT helped him make sense of his own experiences as a Latino Christian. Evangelicals are beginning to reckon with systemic and subtle forms of racism.

The previous paragraph is a true story. But it’s not the truest story. It turns out that more evangelicals oppose CRT than use it as a resource. Dissenters within Cru recently released a 179-page document alleging that the new emphasis represents “a brand new religion of systemic racism, white privilege, and systems of power” that “labels all of Christian theology a racist oppressive ideology of whiteness.” The Southern Baptist Convention nearly imploded last month as institutionalists just barely held off a second Conservative Resurgence that used anti-CRT as a wedge issue. A book entitled Christianity and Wokeness: How the Social Justice Movement Is Hijacking the Gospel by Owen Strachan, who recently went after the old (but “woke”) Divided by Faith: Evangelical Religion and the Problem of Race in America, came out last week. Polls showed that evangelical support for Trump increased between the 2016 and 2020 elections. The efforts of social justice evangelicals to convert their Trump-voting brethren has failed.

The inspirational stories that moderate evangelical institutions tell about themselves isn’t helping. Many marshal a usable history to convince themselves that their tradition is not rotten at the core. Former George W. Bush speechwriter Michael Gerson, for example, appeals to historical examples of nineteenth-century abolitionists and suffragettes. Wheaton College cites Jonathan Blanchard, its first president who made campus a safe stop on the Underground Railroad during the Civil War. Wesleyans, mining Donald Dayton’s Discovering an Evangelical Heritage (1976, 2014), point out that Methodists helped launch the women’s suffrage movement, that missionary E. Stanley Jones integrated evangelistic crusades—soon followed by Billy Graham.

To square this impressive evangelical past with the sordid present, they use the narrative device of historical declension. Evangelicalism, moderates maintain, has declined from its former enlightened stances on issues of social justice. Billy Graham’s legacy has been coopted by his son Franklin. James Dobson, the apolitical psychologist who began tasting the delights of political power, became a culture warrior. Evangelicals who never would have supported Donald Trump in the 1970s voted for him en masse in 2016 and 2020. If contemporary evangelicals would only know their enlightened history—and stay true to it—they would be more willing to say that black lives matter.

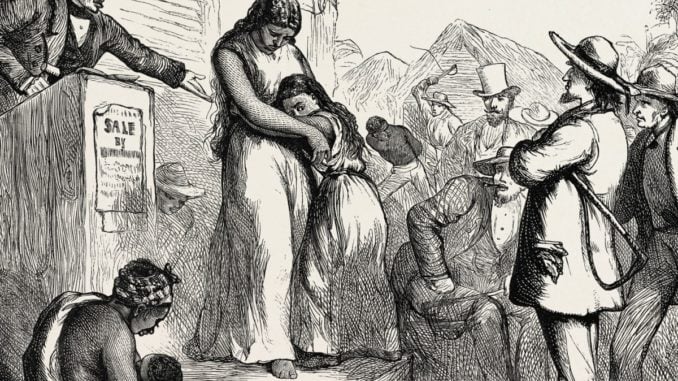

The problem is that these narrations cherry-pick unrepresentative voices from the past. Abolitionists never really represented the mainstream of evangelicalism. There were always more slaveholders than Grimké sisters. Leaders who want to minimize (or distract from) evangelical support for Trump narrate the movement as more cosmopolitan than it has actually been. They peddle what Cuban-American theologian Justo González calls “innocent readings of history.” They minimize the bad, emphasize the good, and ignore how moderation often perpetuates injustice. They portray their own history as more innocent than it actually was.

Telling only stories of evangelical abolitionism, then, is an exercise in missing the point. As told with excruciating texture by Jemar Tisby in The Color of Compromise, white Christian leaders persistently acted out of racial bigotry. For every evangelical abolitionist from the nineteenth-century, there were a hundred slaveholders and thousands who stood silently by. For every evangelical civil rights activist, there were a hundred resisters and thousands of unhelpful moderates who urged King to “slow down.” The single story of evangelical racial benevolence that we usually hear from evangelical leaders feels really disingenuous after reading Tisby.

I hate to come down hard on leaders trying to move their tradition away from toxic aspects of evangelical culture. I like that many now speak of the importance of recovering themes of marginality, pilgrimage, and lament that they say have always pervaded their sacred texts. I like that many missionaries, humanitarian workers, pastors, and evangelical professors say that they live in a new global age that requires a missiology of peace and a posture of submission, not a reassertion of Pax Americana.

But there are significant limits to this kind of usable history. First, innocent narratives allow evangelicals to blame particular historic choices for their sins and avoid deeper questions of identity. They might acknowledge that a nineteenth-century cotton planter chose to purchase slaves—or that a Southern Baptist explained away his opposition to the civil rights movement because he was nice to the black sharecropper in the back of his land. But it’s worth considering what caused these choices in the first place. Perhaps white evangelicals’ recalcitrance on race, perhaps their inadequate definition of racism as a white person being mean to a black person was less the result of a historical choice than a problem with evangelical identity itself. If Michael Emerson and Christian Smith are right, the evangelical cultural toolkit, especially the tool of hyper-individualism, is to blame. And it needs to be discarded—or at least balanced by attention to collective sin embedded in economic structures, national identities, and cultural sensibilities. In short, blaming individuals of the past rather than collective traits is an innocent reading of history that prevents evangelicals from truly pursuing racial justice. Indeed, the evangelical toolkit—especially the individualistic way it explains the world—seems designed to do precisely the opposite: to maintain unjust systems.

Second, reading history innocently ignores the very text that evangelicals hold sacred. Scripture emphasizes lament as much as celebration. Yet evangelicals, notes Soong Chan Rah in Prophetic Lament, pass quickly by the funeral dirges of Lamentations to joyful songs in the Psalms. Justo González writes, “Innocent history is a selective forgetfulness of a more realistic memory. . . . If we read biblical history in an innocent way, we will highlight that King David was a man after God’s heart, but we will never mention anything about his sins of adultery and murder, and thus we will not learn from his mistakes.” Juan Martinez, a professor at Fuller Seminary, agrees, joking that “Latinos are one-point Calvinists” because they have experienced the depravity of humanity. Indeed, all Christian history is a story about broken people.

Instead of trumpeting white successes, says González, evangelicals should listen carefully to marginalized voices. In The Changing Shape of Church History, he maintains that “responsible remembrance,” that is, listening to voices that have been oppressed and decentered, “leads to responsible action.” In Mañana: Christian Theology from a Hispanic Perspective (1990), he suggests that recentering narratives can set us free from “the crippling imprisonment of what we can grasp and take for granted, the ultimate trivializing of our identity.” Indeed, it can “challenge the dominant group in the United States to remember their immigrant roots, as well as the biblical stance toward immigrants: “When a foreigner resides among you in your land, do not mistreat them. The foreigner residing among you must be treated as your native-born. Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt. I am the Lord your God” (Lev. 19:33-34).

Nathan Cartegena offers another biblical example. He notes that in the book of Jeremiah “you’ve got people saying ‘peace, peace, everything’s fine,’ and Jeremiah is like ‘No, not everything’s fine!’ There are those narratives that were designed to blind people to the realities around them.” This sensitivity to history is what Cartegena finds so helpful about critical race theory. He writes, “They’re saying we’ve got to pay attention to the shifts in history and see how differing material conditions and modes of production lead to the production of different legitimizing myths to maintain structural and institutional modes of white supremacy. Because they’re structural and institutional, they lead to people having certain vices of racism — endorsing certain racist ideas and feeling certain racist feelings.”

Erna Kim Hackett gives a more recent example. An innocent reading of the civil rights movement emphasizes the courage of black activists. Writes Hackett, “Which is true, their courage was amazing. But why did they have to be so courageous? What were they facing? The rage, racism, and violence of white people. Rarely is the profound hatred and resistance of white people taught. The evil of white people is downplayed, or minimized, to a few racist exceptions in the South. But white people, all across the United States, resisted any move toward racial justice with fury, rage, and violence. Our history never tells the true story of whiteness.”

This is why Soong-Chan Rah objects to the language of racial reconciliation. He points out that “the idea of RE-conciliation implies within its word structure that you’re going back to something that pre-existed, the idea of being reconciled to a preexisting condition. And that’s problematic, especially for people of color and those who have a history of oppression. What are whites and blacks being reconciled back to? What previous relationship in history are we being reconciled back to? Well, it’s master/slave. That’s the history of the previous relationship between blacks and whites.”

It matters which stories we tell. It’s true that E. Stanley Jones pushed for integration—and that Jonathan Blanchard helped conduct the Underground Railroad. But why were their heroics necessary in the first place? Not answering that question maintains the unjust status quo. Answering that question—that is, telling non-innocent history—gives us a shot at building a more just future.