A senior editor for Guideposts has written a long essay for the Los Angeles Review of Books. That’s a strangely fascinating sentence. (Guideposts, if you’re not familiar with it, is kind of a white evangelical Reader’s Digest — a relentlessly wholesome magazine dedicated to uplifting inspirational and devotional stories, gauzy Christian celebrity profiles, and reader-friendly tales of faith overcoming hardship. The LARB is, well, not at all like that.)

But Jim Hinch’s thoughtful essay on “How the Pandemic Radicalized [White] Evangelicals” is fascinating even apart from that. He makes a compelling argument that the COVID crisis introduced another factor (somewhat) unrelated to the Foxification of evangelicalism and its embrace of the hyper-partisan politics of white resentment. The pandemic, he says, exposed a weakness in American evangelicalism that he attributes to churches’ “outright emulation” of corporate America and corporate management:

And it is here, I believe, that a deeper explanation lies both for evangelicals’ anti-social pandemic behavior and for their larger pattern of divisive, anti-government attitudes. In recent decades, motivated by a combination of evangelistic zeal and everyday human ambition, evangelicals have embraced an explicitly business-oriented approach to ministry that has remade Christianity in the image of corporate America. In 2018, many of the United States’s most prominent evangelical leaders paid tribute to a church growth consultant named Bob Buford, who died that year after a decades-long career regarded by many evangelicals as transformative for their movement. Buford, a Texas cable television executive and disciple of the management guru Peter Drucker, used his personal fortune to bring business principles to evangelical churches. He is credited with catalyzing the growth of megachurches, elevating evangelicals’ longstanding affinity with corporate America into outright emulation.

The resulting “evangelical industrial complex” (so dubbed by critics) has succeeded in its goal of building large Christian organizations and attracting attention to Jesus through a variety of media. …

One thing such churches have proven less able to do, especially at a time of national crisis, is meet people’s everyday spiritual needs.

Hinch argues that this “business-oriented approach to ministry” means many churches are no longer in the business of ministry. That it has turned many congregations — especially mega-churches and those modeled after them, regardless of size — into mere spectators and audiences. Or, as mega-church pastor Rick Warren put it, ““COVID revealed a fundamental weakness in the church. … Most churches only have one purpose: Worship. And if you take worship away, you’ve got nothing.”

Hinch continues:

Over the course of the pandemic, I spoke with dozens of evangelical church members and leaders. I observed a consistent pattern. Churches that were already doing a good job providing pastoral and social services to their congregations and communities weathered the crisis and even thrived, developing new ministries and gaining respect for their work. Size was not a criterion. Churches large and small found success. What seemed to make the difference was a focus on one-on-one ministry and a commitment to local communities. Saddleback, one of the United States’s largest churches, transformed itself into a social services hub, providing food and other resources to local residents and helping to promote vaccines via an online conversation between Warren and National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins, who is himself an evangelical. For years, Saddleback has encouraged members to join small fellowship groups that provide the kind of personal contact and accountability otherwise lacking in large, anonymous megachurch services. In Austin, Texas, medium-sized Covenant Presbyterian Church bought and forgave $10 million worth of local medical debt. Oak Park Baptist Church in Jeffersonville, Indiana, with roughly 400 members, focused on a youth services program that benefits residents of nearby public housing complexes.

By contrast, evangelicals who spoke out most vocally against pandemic measures tended to belong to churches that depend heavily on in-person worship services and the star power of prominent pastors. Such churches suffered from the prohibition of indoor gatherings and left members searching for alternative ways to cope with the pandemic’s many hardships. Leaders fought to return to business as usual. Members gravitated to us-versus-them explanations for their troubles. The rise of pandemic radicalism reflected a massive failure of evangelical ministry.

The central case study of Hinch’s essay is LA-based Grace Community Church, the fiefdom of fundamentalist pastor and author John MacArthur, who initially embraced responsible safety measures early in the pandemic only to later abandon them, litigiously opposing all public-health precautions and ultimately embracing a QAnon-derived conspiracy theory suggesting that the virus was a “hoax.”

MacArthur’s authoritarian leadership as CEO of a business-model church, Hinch argues, meant that Grace Community Church was wholly unprepared to meet its members physical and spiritual needs when the pandemic hit:

In a January sermon, MacArthur spotlighted some of Grace Church’s accomplishments during the pandemic. Atop his list was holding in-person services in defiance of local authorities and suing Los Angeles County. To address community needs, MacArthur said Grace donated orchids to local police stations, celebrated a police officer’s retirement, gave away $70,000 worth of food to families in the congregation, distributed MacArthur’s books in prisons, and protested outside an abortion clinic. For comparison, I inquired about pandemic outreach at Mariners Church, a megachurch in nearby Orange County similar in size to Grace that for years has prioritized local service work. Chief Content Officer Cathi Workman told me that Mariners provided childcare for essential workers, offered workspace and technology assistance to families adapting to online school, delivered more than 1,000,000 meals, held blood drives, and helped to provide services for local adults with special needs. Workman said Mariners complied with local health orders and sought to keep politics out of pandemic ministries. “I see most churches just honestly, humbly trying to navigate an era that no one has seen before,” she said. “A lot of creativity is emerging.”

Last week we looked at the irksome, artificial dichotomy of “vertical vs. horizontal” religion. Discussions that accept that framework usually portray an emphasis on “vertical” religion as more conservative while an emphasis on the “horizontal” is characterized (and somewhat devalued) as more “liberal.” The idea, I suppose, is that bleeding-heart progressives are inclined to get so caught up in loving their neighbors that they cease to care about loving God — eventually abandoning worship, prayer, and doctrine entirely and becoming indistinguishable from any purely secular group of do-gooders.

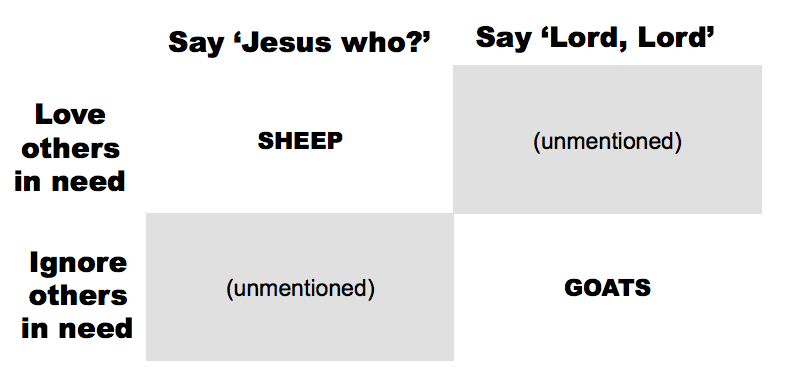

The curious thing about that framing is that this “danger” of “flattening” religion into a purely horizontal focus on love for one’s earthly neighbors (and enemies) isn’t something the Bible warns against. If we read the Bible, instead, what we’ll find is dozens of examples warning of the opposite danger — reducing love for God into a purely “vertical” focus that neglects love for earthly neighbors. We’ll also find multiple examples — Matthew 25, Zacchaeus, much of Isaiah — that seem to commend or even command this horizontal flattening. “Go away,” Jesus says, “and don’t come back until you’ve learned what this means: ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice.”

None of the “sheep” have any “vertical” faith. All of the goats do.

Yes, again, I don’t want to argue that such passages really intend for us to wholly abandon the so-called “vertical” aspects of faith for an exclusive focus on justice and love of our neighbors. I think they’re just emphatically teaching that, as 1 John 4 says repeatedly, it is impossible to love God without loving our neighbors. But biblical examples of this wholistic fusion of “vertical” and “horizontal” faith are still as rare as milk-chocolate Mounds bars.

The point here is that Rick Warren is only half right when he describes haplessly “vertical” churches like MacArthur’s. Such churches, “have one purpose: Worship,” Warren said. “And if you take worship away, you’ve got nothing.”

I’d amend that. If a church has only one purpose: Worship, then that church has got nothing even if you don’t take worship away. Because if all you have is “worship,” then you don’t even have that. You’ve got something else. You’ve got a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal. You’ve got some shallow, hollow, counterfeit that you’re pretending is “worship,” but that, from God’s point of view, is “detestable” and “futile” and “an abomination.”

That’s what Isaiah 1 says. And Isaiah 58, and Matthew 25, and 1 Corinthians 13. If all you’re doing is “worship,” then whatever that is, it ain’t worship.

And it won’t be of any use or help or guidance when the plague arrives.