[ On July 5-7, The Ekklesia Project will hold its annual gathering in Chicago, which will be on the theme of Slow Church. Between now and July, we will be running a series of lguest reflections here by folks connected with the E.P. We’ve asked guest posters to reflect on the meaning of Slow Church from their own local contexts. More info on the E.P. gathering. ]

[ On July 5-7, The Ekklesia Project will hold its annual gathering in Chicago, which will be on the theme of Slow Church. Between now and July, we will be running a series of lguest reflections here by folks connected with the E.P. We’ve asked guest posters to reflect on the meaning of Slow Church from their own local contexts. More info on the E.P. gathering. ]

Today’s reflection, the third in the series, is by Edwin Searcy.

Read the previous post by Jason Fisher.

I am learning to pastor a slow church. I am cultivating habits of patience and trust that God is forming a distinctive, faithful people year by year. When I became the pastor of Vancouver’s University Hill Congregation in 1995 I had no idea that I would still be the pastor seventeen years later. Now, looking back, I realize that this was to be my school in pastoring a slow church.

It was thirty years ago that University Hill Congregation was facing the painful decision to sell its church building and property. The small congregation simply could not afford the burden. The future did not look promising. But the congregation was able to rent the local theological school’s chapel on Sunday mornings. Now, three decades later, the congregation is being formed into a distinctive community marked by a variety of common practices.

One of those practices was instituted by an interim minister who arrived for a year just as the congregation moved from landlord to tenant. He initiated the role of a “Worship Elder” in the Sunday liturgy. This lay member of the congregation is responsible for preparing the Prayers of Approach and Confession, the Prayers of the People and the Commissioning. These prayers are not printed but are spoken by the worship elder. The practice continues to this day. Over the years we have offered a variety of sessions to teach worship elders about the nature of public prayer and to assist them in their calling. Now this teaching seems to come by osmosis as the congregation overhears the care and passion the worship elders put into the prayers. We are learning how to pray by listening to one another pray.

What has been the effect of fifteen hundred Sundays of lay led prayer in the congregation’s life? It is not easily measurable but it is tangible. A variety of worship elders offer the prayers. In learning to craft and lead the prayers they report they have become more active participants in the prayers of the congregation when they are not serving as the worship elder. It is evident that prayers which were once more perfunctory have become a natural part of the congregation’s life and rhythm.

In a denominational culture which has long been uncomfortable with testimony the worship elders’ offer their witness each Sunday. We ask them to tell the truth about us to God. The prayers are a bold testimony to the faith of the worship elder and of the congregation. This isn’t the minister’s precinct. This is the work of the people. Thirty years ago this was an innovation. Today this is simply who we are.

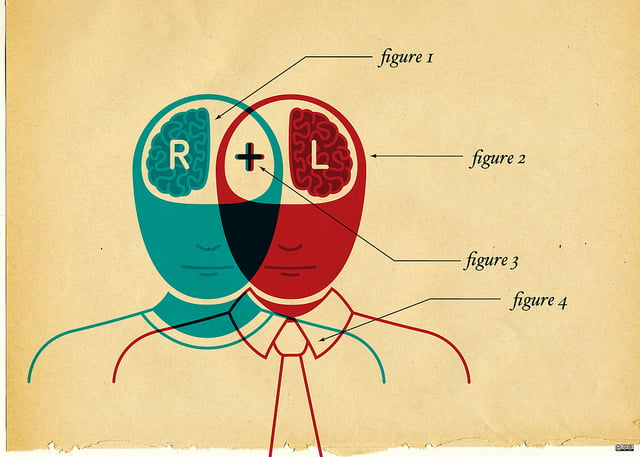

Another of the practices that mark the life of University Hill Congregation is a commitment to move from Bible study to hosting scripture. For the past dozen years we have used a hermeneutic of hospitality to describe our relationship with the text that roots and forms us. Instead of studying the Bible in order to discover its meaning we view a scripture passage as a holy stranger sent, like Abraham and Sarah’s guests, from God.

We model this hermeneutic in the pulpit, asking any who preach the Word to host the text and to listen with care for a Word to us in this time and place. If the text is strange to us we think of how we might best host a dinner guest who comes with a peculiar message. We don’t silence the stranger, though we cannot understand how this message could be from God. We listen with curiosity for the Word that is for us, even if we rather it not be spoken. Like Jacob we are prepared to wrestle with the guest until we receive a blessing. If the guest is familiar to us we remember not to assume that we already know the message before we begin. This is akin to imagining that we already know so much about our spouse or sibling or friend that we don’t really need to listen for anything new anymore.

Adopting a hermeneutic of hospitality changed the sermons at University Hill. A congregation that meets to worship on a university campus is tempted to privilege teaching about the text in its preaching. However, when the preacher hosts a text the sermon sounds much more like testimony in a court room than a lecture in a classroom. The sermons that result are regularly rougher around the edges, more open ended, allowing the text to speak its odd message.

But it is not only the preacher who is called to host scripture. We wondered how the congregation might grow in its capacity to interpret scripture. Twelve years ago we began an annual Lenten Daily Devotional. Each year we select forty seven texts for the pilgrimage from Ash Wednesday to Easter Sunday. Then we invite folk to offer themselves as a host. Each host is assigned a text, asked to host it on our behalf and then to offer a testimony that speaks the Word they hear from God to us . At first many felt ill-equipped for the task. They said that they were not experts in the Bible. We told them that we weren’t looking for experts. We said that we were looking for disciples who are prepared to grow through disciplined practice.

This annual Lenten devotion is now part of the regular rhythm of our life. What was once printed in booklet form is today available online. It means that every year forty-seven of us engage in the interpretive practice of hosting scripture on behalf of the church. And it means that every year forty-seven testimonies are offered in the congregation as a witness to what God is up to in our life together.

My education as a pastor of a slow church owes debts to many different teachers. Key in my formation as a slow church pastor was George Lindbeck’s The Nature of Doctrine. My copy is well marked and dog-eared. One high-lighted and underlined sentence, in particular, summarizes what I have been learning in these past seventeen years: “This conclusion is paradoxical: Religious communities are likely to be practically relevant in the long run to the degree that they do not first ask what is either practical or relevant, but instead concentrate on their own intratextual outlooks and forms of life” (128). I was formed and called into ministry by a denomination that cherishes “relevance”. Imagine my surprise to discover that my life calling would be to become an apparently irrelevant pastor. Such is life in the slow church. I am grateful for it.