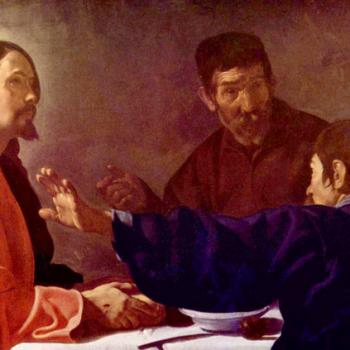

When I was in a conservative Presbyterian denomination there was never the Lord’s Supper observed except that the table was properly fenced.

“Fencing the table” meant giving everyone a careful explanation of who was welcome and who, for their own good, needed to stay away. This was an attempt to take seriously the warning of Paul: “The one who eats and drinks, eats and drinks judgment to themself if they do not judge the body (of the Lord) rightly.” The admonition to examine ourselves was offered, even as the meal itself was promised as a means of grace.

It was jarring for me, then, to later find myself in churches where the communion table was simply a place of invitation. The idea that this meal, a memory of and participation in the death of Jesus, was a tangible proclamation of our Christian message meant that anyone who needed to hear that word of grace was welcome to come and experience it in comestible form.

This difference in posture is one illustration of the ways that a line runs down the middle of Christian (and American) culture. It is a line separating those who primarily define faithfulness and morality in terms of purity and those who define faithfulness and morality in terms of participation.

Confessions of the Purity Averse

I confess: I am purity averse.

As the snippet of my above hints at, I wasn’t always this way. I spent a good bit of time being excited about being a Confessional Presbyterian. Guarding doctrine, guarding behavior, guarding the Table—these are empowering pursuits, especially when you’re a nerd.

But then, over a period of nearly five years, I went through the most important, formative experience of my theological career: I was puritied out. My theology wasn’t pure enough to get licensed to preach in my Presbytery. So I was never licensed. I was never ordained.

I watched a dream die. Honestly, I watched myself die.

But when that purity seed fell to the ground and died, something more fruitful sprang up in its place. I now knew what it was like to be blocked from the table and pulpit of the Lord by those who had taken the power over it to themselves. I began to recognize that the posture of the guardians of purity was not wrong simply because they were using the wrong standards of judgment (an 86 page confession written by an illicit regicidal assembly in the 17th century), but because the posture itself was antithetical to the gospel.

So my true confession is this: I have little patience anymore for purity-driven Christianity or purity-driven social legislation. Because now I know through experience what, before, I had only heard with my ears: purity cultures destroy people.

The Call to Purity

The problem for me in this, as a biblical scholar, is that the calls to purity, and the definition of the people of God as a holy people, confronts us all over the place in scripture. Purity culture is not just something that an anal-retentive priestly writer made up, saddled Judaism with, and that Jesus then had to free us from.

The teachings of Jesus call for purity of eyes and heart. They offer ways of confronting impurity and expelling those who bring it in.

And sometimes, getting the teaching right really does matter.

So the question I’m wrestling with right now is this: is there a way to hold these things together? Or do we simply attempt to extricate ourselves from the lure of pursuing purity?

Perhaps where we go wrong is in how we define or attempt to live out purity, such that it becomes a standard to measure whether other people have their theological or moral crap together as well as we do.

But might it be that the purity that should mark us is the purity of a people who always ensure that every person we meet knows that they are profoundly loved by God? Maybe the purity we need to pursue is the purity of heart that drives a whole community to strive to lay down our lives so that others might truly live.

Maybe the exertion of power that keeps people who think like us and act like us in charge while forcing others to conform or get out–maybe that’s the impurity that needs to be most deeply rooted out of our hearts?

Back to the Table

Who we eat with says a lot about us. I think we tend to find that idea antiquated, like it was a big deal in the first century who you ate with, but we don’t really care that much.

But no. The restaurants we eat at mark us as participating in a certain social and economic circle. The homes to which we get invited (and those to which we don’t) show us something about where we stand in relationship to other people. The people we invite over show us who our people are.

And then there’s that pesky Lord’s Table. Is there some way that we might have that be an expression of purity and participation? Can we even honor Paul’s warning about judging ourselves, and the body, rightly, while offering it as a means of grace to all?

I think so.

In Corinth the problem was this: the rich and powerful were feasting at the “Lord’s Supper,” while the poor folks had to come later, after they had waited on their own masters. The have-nots were going hungry while the haves were feasting together and getting drunk.

What they were misjudging when they came together was the identity of the people of God. They were misjudging who mattered. They were misjudging the nature of God’s embrace of them in Christ.

They were not embraced because they followed the right apostolic teacher. They were not embraced because they had the gifts of knowledge and teaching and preaching. They were not embraced because they were more “blessed” with social standing and financial resources.

They were embraced because of the cross of Christ. And they were embraced right alongside everyone else who is part of that body, right alongside everyone else who needs to be liberated from the powers of oppression–from the very powers they were exercising in the church.

What would a pure Lord’s Supper look like in Corinth?

It would look like participation. It would look like embrace. It would look like the reign of God had created a different kind of society in which the impurity of classist and racial and gender division and hierarchy was gone and all were one.

Living that out–that’s what judging the body rightly would mean. That’s the purity of the people of the God.