Communities of Strangers

Monasteries are like many other organizations in quite a few ways.

Organizations attract people from a wide variety of locations and educational backgrounds. People bring their own personalities to an organization. Lots of organizations draw people with diverse strengths and skills.

Getting people to work well together is one of the most significant challenges for any organization.

Corporations, nonprofits, and other groups look for people who share core values. Even if people have different ways of understanding those values, sharing them is essential.

Each organization is its own unique community, even those which may appear disorganized. As people experience how they work together they discover how the community functions.

Whenever we work with anyone we have not met before we are creating communities of strangers. Powerful organizations are formed by sorting out how we will live and work together.

Monasteries rely on many of the same dynamics as corporations and other organizations. There are differences, but the similarities are powerful.

Those of us who lead in other groups can learn valuable lessons from monastic communities.

The monks of each community come from many different places and backgrounds. Their skills, education, and experiences complement each other and strengthen their community.

Each community draws in members who share its core values. There are misunderstandings and conflicts, like any other group. Communities work to resolve and transform these tensions in ways which help them become stronger.

As monastic communities of strangers work together they becomes familiar. Members who enter the community as strangers become brothers and sisters.

Recruiting New Members

Monastic communities tend to recruit new members in their own unique ways.

Monasteries generally do not recruit people from other monastic communities. There is very little monastic marketing. Monks do not receive signing bonuses.

Monastic communities do not actively discourage new members, though they can be intimidating. Potential new members are encouraged to be intimately acquainted with their true selves. Long periods or reflection, preparation, and assessment are part of beginning monastic life.

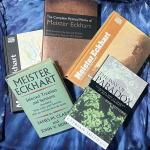

As a lay Oblate, I spent a year practicing monastic disciplines. It was important for me to become accustomed to them and make sure they fit me well.

New Camaldoli hermitage, where I am an Oblate, has the Rule for Oblates on its website. I knew what the practices were before I turned in my application.

It was not a test I needed to pass or an interview for me to survive. Their concern was whether the life of an Oblate was a healthy one for me. They were not trying to add to their list of prestigious Oblates.

Monastic recruiting can appear to be the opposite of how we add members to other groups.

My community seemed to be more concerned with my discernment than its own strength. The process was a time of reflection for me, not filled with insecurity about whether or not I would be chosen.

Becoming a lay Oblate was not like being recruited or hired by a company.

My year of preparation, of postulancy, led to being received as an Oblate. I had ample opportunity to ask questions and find the truth for myself.

Being received was both a completion and a beginning.

Formation and Orientation

When corporations and other organizations recruit new people, there is a period of training. Often called orientation, a group tries to make sure everyone is on the same page. New people receive copies of policies and procedures, or a handbook, or watch videos together.

The idea is for an organization to orient people, to point them in the right direction. People hired at about the same time often train together and get to know each other.

Monastic communities do not talk in terms of orientation, but of formation.

The more extensive process of preparation has introduced new people to the community. There are usually not as many rules and procedures to follow. Discernment and preparation have already revealed how people are oriented.

As we lead in various organizations we learn how to train and orient new people. Some leaders try to explain as much as they can in as much detail as possible. Other leaders prefer to observe as people learn for themselves.

Monastic formation is often a more one-to-one experience. Not focused on policies or procedures, new members of the community adapt to monastic life. New monks may need to develop specific skills or abilities. The overall concern, though, is how monastic life fits with them.

Monastic communities are intended to develop the members’ capacity for deep reflection.

Over time, communities of strangers develop into families.

Monastic Leadership

Leading in a monastic community does not focus as much on meeting objectives.

In a corporation which produces a product or service, production deadlines are crucial. The key to an effective operation is producing high enough quantities with quality.

Monasteries work differently.

While monastic communities produce things to generate revenue, spiritual life is the bottom line. Each member is encouraged to spend time in reading and reflection. A monk searches his or her own heart to find the sacred truths there.

Monastic leadership is more focused on each member of the community.

As each member of a monastic community goes deeper, the community grows stronger.

Turning Communities of Strangers Into Families

Family relationships can be more complex than how we relate to strangers.

We have developed a history with our families. We know them and they know us.

Some relationships grow more healthy as monastic life turns communities of strangers into families. Others produce tension and strain.

Like in other organizations, leadership in monastic communities is about bringing out the best in people.

As we get to know each other we may begin to trust and depend on each other.

Monastic communities face many of the same challenges as other organizations.

People enter as strangers and develop into family.

How will we help communities of strangers become family this week?

Where does our leadership encourage strangers to become friends?

[Image by amandabhslater]

Greg Richardson is a spiritual life mentor and leadership coach in Southern California. He is a recovering attorney and university professor, and a lay Oblate with New Camaldoli Hermitage near Big Sur, California. Greg’s website is StrategicMonk.com, and his email address is StrategicMonk@gmail.com.