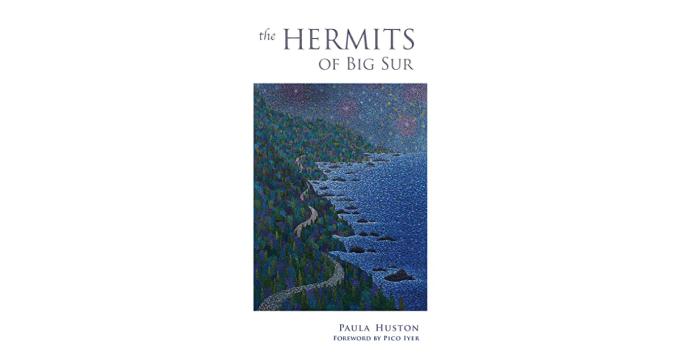

My guest today is Charles Kruger, a San Francisco Bay area arts practitioner also known as “The Storming Bohemian.” As a “late emerging” artist, who began pursuing this career when he was past 50, Charles has a passion for encouraging others to explore their artistic potential, while pursuing his own projects enthusiastically. He writes, paints, and organizes literary events among other “arts” activities. He is a grateful oblate of New Camaldoli Monastery. Charles has written his review and reflections on The Hermits of Big Sur by Paula Huston.

The Hermits of Big Sur

Some years ago, I attended a retreat at New Camaldoli Hermitage in Big Sur, California. At the time, I was a lonely gay guy in my thirties, teaching middle school, not very happily, in the small town of Lompoc, an alcoholic with a few shaky years of recovery under my belt, with a hunger for spirituality.

I read somewhere on the internet that a Catholic monk in Big Sur was going to lead a retreat on spirituality for gay men. Is such a thing possible, I wondered? I thought I knew something about monks. After all, I had read Merton’s “The Seven Storey Mountain.” Monks took oaths of silence, lived cloistered lives, never left the monastery, prayed for hours every day and sometimes wrote books. They were sexless, mostly conservative, more than a bit odd, and certainly had nothing to say to me as a gay man. But I was desperate. And I figured, what could I lose? I was lonely, and in need of spiritual sustenance. Maybe I could kill two birds with one stone? Befriend some fellow gay retreatants and get a taste of the holy over one long weekend? I certainly thought it was worth a try.

I contacted the monk/priest who was leading the retreat. He told me that the weekend was full up, but then offered to find a place for me. I was in.

Introduction to the Hermits of Big Sur

Two weeks later, on a Friday night, I set out on the long, beautiful drive along the world-famous cliffs of the Pacific Coast Highway and found my way to the “Immaculate Heart Hermitage,” better known today as New Camaldoli, arriving at the entrance two miles above the boiling sea. I had been setting out one way or another all my life. At 16 I had been a teenage runaway. In my late twenties, I embarked upon the path to recovery from alcoholism. Soon after that, I pursued a teaching credential. After a miserable first year of teaching in the dysfunctional Los Angeles Unified School District, I made my way to the much smaller Lompoc School District and became a lonely country boy. And now I had set out to the cliffs of Big Sur to a Catholic Monastery. I am a man who sets out, but rarely arrives. How could I know that this time, after all my wanderings along twisted roads, I had come home?

But I was late. It was well after dark, and I had expected to arrive at least an hour earlier, to attend the opening session of the retreat. I passed the entrance sign and followed directions to the Monastery bookstore where I came to a stop on a graveled parking lot. I sat for a moment, after driving for four hours, turned off the ignition and finished rolling down the window. It was incredibly silent. I could smell the Pacific Ocean and many other less familiar scents. There were several cypress trees visible along the edge of the parking lot, shadows against the starry sky. I could see more stars than I had ever seen in my life. There were a few other parked cars in the driveway. I must be the last to arrive. Had I ever been some place as quiet as this? There was no sound from the highway two miles below, or from the sea. I knew the sea was there, I could see the shine of whitewater on the crashing waves reflecting the amazing starlight. But I could hear nothing. It was pleasantly cool. I was glad I was wearing my favorite green sweater that went well with my brown eyes (I had not forgotten I was hoping to meet some other gay men). There was an empty M&Ms bag on the seat next to me, and on the floor I could see that I’d dropped my school lanyard with the attached name tag. I removed the keys from the ignition and rolled up the window and stepped out of the car.

I was startled and momentarily embarrassed by the sound made when I slammed the car door—it was like a gunshot. But that embarrassment was nothing to what I felt when my car alarm suddenly went off, siren playing and horn blasting: Honk! Honk! Honk! Honk!

Uh oh, I thought, and stumbled to reopen the car door and turn the darn thing off. Then I stood by the car, heart pounding, thinking, “This was a mistake. I don’t belong here. They are certainly going to send me away for disturbing the quiet.”

Meeting the Hermits of Big Sur

I leaned into the car and silenced the alarm. Standing up, I saw a monk approaching, wearing a white habit. He looked at me. “You must be Charles,” he said. I thought he seemed amused, and hoped he was.

“Um, yes,” I said. “Sorry for the car alarm.”

“It’s alright,” he told me. “Please come along with me. We’ve already begun.”

He led me to a room by the church. Two or three robed monks were there, along with several men seated in a semicircle around a beautiful young monk with a guitar.

“Hello,” he said. “Thank you for coming, please join us.”

Brother Musician was talking about his life before the monastery. Shockingly, he spoke of sexuality and promiscuity. And how all of that was okay and had never been a bar to spirituality. It was just another part of the search for God, he told us. Remember St. Augustine. Then he tuned his guitar and began singing a song he had composed, a setting of a poem by Rumi. He began, “There’s a moon in my body . . . ”

I was gob smacked. By the time the weekend was over, I knew I would remain connected with the monastery forevermore and that is exactly what happened. Some years later, in Berkeley, I was welcomed into the Camaldolese community as an oblate (lay associate) of the monastery.

Over time, I learned from reading, conversation, and direct experience that the Camaldolese Order (part of the Order of St. Benedict) is the oldest continuous monastic community in the West dating back to the eleventh century in an uninterrupted line. But I have often wondered how it was that this ancient Catholic religious order wound up with a monastery in the midst of the hippies and counter culturalists of Big Sur, counting yogis and Zen masters, progressive political activists, poets, journalists, scholars, cooks, charismatics, chemists, musicians, eccentrics, liturgical celebrities, and modern anchorites (strict hermits who live in total isolation) among their fraternity.

I mean, who knew?

The Story of the Hermits of Big Sur

Now, one of the community’s long term oblates, distinguished novelist and spiritual essayist Paula Huston, has written a history, “The Hermits of Big Sur,” which rends the veil of the cloister to reveal how the community of New Camaldoli, born as a vision amidst the turmoil of World War II politics, and later manifested during the upheaval of Vatican II and the emergence of the counter culture of the 1960s, came to find its unique path into our new millennium.

Originally, it was the intent of the Camaldolese to build a hermitage in the mountains of Big Sur. It would be a place entirely removed from the world—as strict as strict could be. The monks would be silent. They would live in remote cells and would not interact except to pray together in choir. There would be no visitors, no retreat house, no biographies, no public face. The monks of New Camaldoli were wildly ambitious to be entirely without ambition. They would be rugged, to say the least. It is rumored that at least one of those founding monastics wore a hairshirt and drew blood with self flagellation.

The story of how these rather extreme beginnings morphed over the years into a center of ecumenicism, a welcoming retreat to thousands of visitors, a friend to the hippies and new age activists of Big Sur, a haven for feminists, yogis, Zen priests, protestant ministers, and purveyors of the movement for a “new monasticism” among the laity—all this while still fully honoring monastic tradition and providing cells for hermits to fully commit to their vocation even in the midst of all that (relatively speaking) bustle.

Reading The Hermits of Big Sur

As Paula Huston tells it, the history of this monastery is a story of international intrigue with, astonishingly, links to fascist spies, Jesuit diplomats, multiple Popes, Mussolini, California millionaires, rock and roll, hot tubbing hippies, the Charismatic Renewal Movement, an Indian ashram and more.

Huston uses her impressive skills as a storyteller to bring events and the characters to life. Among the monks are a rock and roll musician who eventually became prior, two labor activists, a chemist/scientist, an actor, an admiral’s personal chef, at least two artists, and a composer/writer/linguist/liturgist/ theologian/former disciple of Paramahansa Yogananda/expert on Yoga/and Esperanto aficionado. The last mentioned may well be a candidate for a listing in Ripley’s “Believe It Or Not.”

Could these men really be vowed monks in the oldest continuous monastic order of the West, dating from the eleventh century? Indeed they can.

The publisher’s blurb accurately describes this book as “the compelling story of what unfolds within this small and idealistic community when medievalism must finally come to terms with modernism.”

That is exactly what the book delivers.

Readers who believe in the Holy Spirit will be moved and astounded at the history of Its seemingly miraculous manifestation in Big Sur, California.

Those who have never believed may be moved to ponder.

[Image by Paula Huston]

Greg Richardson is a spiritual director in Southern California. He is a recovering assistant district attorney and associate university professor, and is a lay Oblate with New Camaldoli Hermitage near Big Sur, California. Greg’s website is StrategicMonk.com and his email address is [email protected].