I decided to read a Tom Wolfe novel recently. First of all, as a tribute to his life. Secondly, because I discovered he was fascinated by neuroscience (as all the best people are). I was curious to find out if he addressed the philosophical implications of brain research, so I picked up I Am Charlotte Simmons.

I Am Charlotte Simmons: the plot

The novel’s protagonist is a wholesome 18-year-old girl from Sparta, a tiny rural community in the mountains of North Carolina. Charlotte is not only an academic prodigy, having scored a perfect 1600 on the SAT, but a paragon of God-fearing small-town virtue.

The plot opens as Charlotte is finishing her senior year of high school as the valedictorian, and preparing to attend Dupont University – an elite institution evidently modeled after Duke. Upon her arrival, much to her disappointment, Charlotte discovers that Dupont is not the lofty center of intellectual life that she had expected.

Through Charlotte, Wolfe introduces his readers to his theory of college campus life: that it is dominated by the struggle for status, sex, and success.

Wolfe presents three different faces of student life at Dupont. First is collegiate athletic life, explored through the character of Jojo Johanssen, a starter on Dupont’s nationally-ranked basketball team. Next, there is Greek life, embodied by boys of the Saint Ray fraternity and their girlfriends. Finally, there are the misfits who embrace the intellectual life and left-wing politics. As Charlotte navigates this world jocks, frat boys, and dorks, she strays from her upbringing and – in true Tom Wolfe style – suffers repeated humiliation and failure.

My response

To be honest, I wasn’t a fan of the novel. Much of the it was nauseatingly hyperbolic. It also failed to explore its subject matter with enough depth. However, I do give Wolfe credit for presenting a fairly accurate picture of undergraduate life on an elite college campus.

The most interesting part of the novel was Charlotte’s wrestling with the darker side of neuroscience theory.

Neuroscience theory and the self

This theme is most explicit in Charlotte’s Introduction to Neuroscience course, taught by a fictional Dr. Starling.

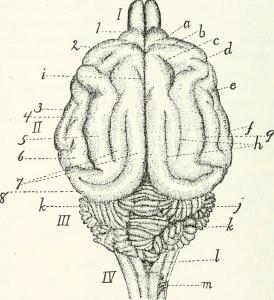

The novel begins with a description of the experiment that won Dr. Starling a Nobel Prize. In this experiment, Starling removed the amygdala from thirty (out of sixty) cats. These “amygdalectomized” cats acted deranged, overwhelmed by sexual desire. Starling then showed that the thirty healthy cats, after observing the amygdalectomized cats, would act the same way.

The conclusion? An animal’s behavior is determined by its social and cultural atmosphere. The implication: so is human behavior.

Later in the novel, Dr. Starling lectures on (real-life) neurobiologist Jose Delgado. Among other discoveries, Delgado is famous for mapping the brain through electrical stimulation. Starling highlights one experiment, in which Delgado eliminated the aggressive instinct of a charging bull by stimulating an electrode in its caudate nucleus.

Moving immediately from science to speculative philosophy (classic move), Starling claims that this experiment proves that “purpose and intentions are physical matters.” The human mind, according to Starling, is not at all how we conceive of it. The self a mere illusion. Free will is nonexistent.

This attitude is prevalent among modern theorists of neuroscientists. They take Descartes’ cogito and, failing to find any ghost in the machine, reject the existence of a self apart from the brain. Then, they take it a step further, theorizing that all aspects of the perceived “self” can be explained and even predicted by a system with sufficient computational power.

Taken together with genetic theory, this leads to a Nietzschean triumph over the soul. The result is a wholly postmodern culture: the self is a thing of the past, God is dead, and neuroscience reigns.

A defense of the self?

Needless to say, Tom Wolfe finds this attitude not only unappealing, but false. However, I am Charlotte Simmons does little to rebut it. Over the course of the novel, she shows no moral courage to resist peer pressure. Charlotte wholly abdicates to the pressures of her environment.

So perhaps Wolfe’s rebuttal of scientific determinism occurs on a different plane. As Wolfe knows well, there is a dividing line between neuroscience and genetic theory. In an interview conducted by Michael Gazzaniga, father of cognitive neuroscience, Wolfe cites José Delgado as saying that the human brain is complicated beyond anything we can imagine.

“The human brain is enormously complicated. We have made only a few small steps in finding out how it works. All the rest is literature.”

All the rest is literature, indeed. Wolfe’s Dr. Starling – modeled after Dawkins and other theorists – may speculate on the basis of neuroscience discoveries, but his ideas remain exactly that: speculation. His philosophical conclusions from neuroscience experiments are not science. They are speculative theory. Even if Dr. Starling were right, and there were no soul and no self, scientific experimentation could not lead to this conclusion.

Further reading recommendations

On scientific determinism, check out Daniel Dennett (a compatibilist) and Sam Harris (an incompatibilist).

This study raises some issues with the experiments most cited as evidence against free will.

For more on the campus culture portrayed by I Am Charlotte Simmons, check out Mary Ann Glendon’s review of the novel in First Things.