There has been a surge of interest, in recent years, in identifying the neural correlates of religious experience. Some scientists, particularly Sam Harris, have used this as a methodology to attack religion and portray it as a backward set of biased assumptions. However, we need not be afraid of this line of scientific exploration. When conducted well, and when its limitations are understood, it can enrich our understanding of prayer, and perhaps improve our prayer lives as well.

So what does neuroscience tell us about the “cry of the heart”?

-

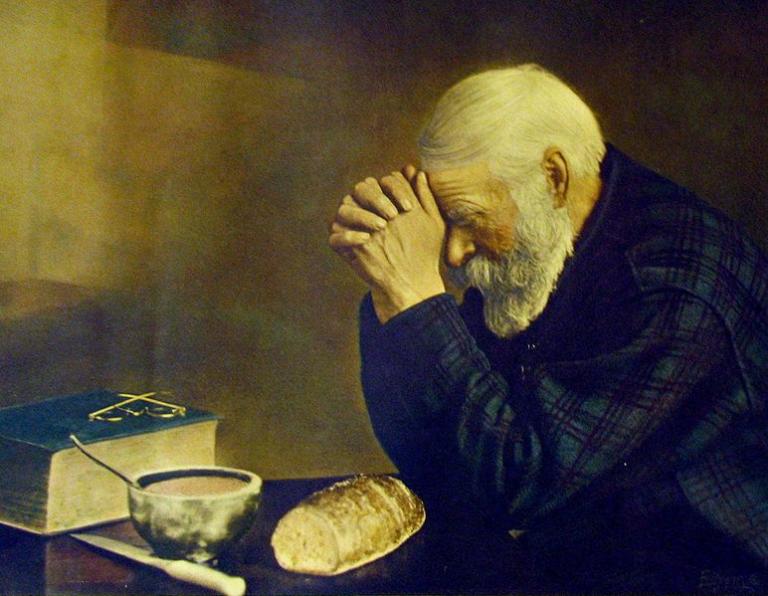

Prayer is participation in a relationship with God.

The same brain regions activated by prayer are those involved in speaking to a loved one. In particular, this study shows activation of regions are involved in theory of mind (understanding another’s unique perspective) and the default mode network (evaluating past and future experiences of self). The study was conducted in evangelical or charismatic groups; I think Catholics can learn from these groups how to incorporate more interpersonal dialogue in mental prayer, how to experience God’s intimate nearness. For after all, in the words of St. Augustine, God is closer to us than we are to ourselves.

-

Prayer is incredibly good for you.

Forms of prayer have been linked to psychological and biological changes for greater health. Regular prayer reduces blood pressure, heart rate, and improves your heart’s synchronization with your breathing. Prayer about God’s love alters levels of key hormones like melatonin, and neurotransmitters like serotonin. The immune system gets a boost too, and disease states are improved. More broadly, pain and anxiety states are blunted, while positive mood spikes. And in studies comparing the effects of secular meditation to those of prayer, prayer undeniably comes out on top.

In the words of Fr. Giussani, it is “the request to God that sets you right, that sets you back on balance, that makes your eyes lucid again, that gives strength to your heart.” Thus, “that reading the Psalms of Lauds, of Sext, of Vespers and of Compline, reading the Psalms with attention renews all of you, serves to renew all of you.”

-

Prayer changes your brain function.

How do these effects come about? Regular prayer boosts the activity of the anterior cingulate cortex. This is a part of the brain implicated in affection, compassion and empathy. It also decreases activity in the parietal cortex. Ordinarily, this cortex is activated when you’re thinking about yourself, suggesting that prayer helps you feel “at one” with the Lord. Finally, striving to be united to God’s love increases the activity of the frontal lobe, the rational area of your brain responsible for higher-level thought. This shifts activity away from your lower-brain, responsible for emotions and more basic instincts.

Importantly, praying about God’s wrath may have the opposite effect, shifting activity from the cortex to your limbic system. This elevates your stress response, which has detrimental effects on your health. Praying about God’s anger also makes us less likely to forgive ourselves and others. This is not to say there’s never a place for experiencing God’s anger; it can be a powerful driver of behavioral change. However, fear of God should be united to rest of the gifts and fruits of the Holy Spirit.

-

But we haven’t studied the healing effects of prayer.

Often, we pray for healing from illness and disease. But the scientific literature on the healing effects of prayer is conflicting and riddled with factors that confuse results. First, prayer that is supported by deep faith may be associated with all the benefits of the placebo effect. Second, there is a phenomenon called spontaneous remission, significant medical improvements in a disease that ordinarily progresses. This happens in individuals who do not pray, and it may occur merely coincidentally with prayer. Third, the patient may experience regression to the mean, or a normal fluctuation of the severity of the illness. Finally, the patient may experience improvements due to nonspecific social support in group prayer. These are more likely to be understood as the effects of divine intervention.

However, these effects don’t “disprove” the effects of prayer. Rather, they could perhaps be natural mechanisms through which God responds to prayers asking for healing, because divine healing doesn’t have to be a bolt of lightning from the sky.

-

We have a long way to go.

As powerful as these methods are, neuroimaging studies face severe limitations. So far, we have yet to find a way to measure changes in neurotransmitter levels and micro-circuitry structure, in an ethical and non-invasive way. Furthermore, differing definitions “prayer” involved make it harder to generalize results from multiple studies. They also fail to measure confounding variables, like faith and religiosity.

So prayer remains a mystery, scientifically speaking. But given what we do know, we have good reason to follow St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, who exhorts us:

We must pray without ceasing, in every occurrence and employment of our lives – that prayer which is rather a habit of lifting up the heart to God as in a constant communication with Him.

Further reading recommendations

Fr. Thomas Dubay’s Deep Conversion Deep Prayer offers an overview of the spiritual life and practical advice for developing a deep prayer life.

For more of the neuroscience research, see the work of Dr. Andrew Newberg.