Earlier this week I had the pleasure of chatting with Jen Fulwiler on her radio show.

We covered a lot of ground in 18 minutes, in particular touching on a topic that deserves some lively thought — assuming one ever has time to think — on the paradox of good intentions: we in the church serve the poor and advocate for them. We devise programs and policies meant to lift people out of poverty and into prosperity, and when we are very successful at it, then as a church we suffer.

We suffer due to shortages of priests, and emptier pews, because a prosperous society is too often a society that feels so self-sufficient that it doesn’t “need” God — feels no need to lean on faith.

Here on Long Island, our priests are increasingly hailing from what have been the poorest parts of Africa, Asia and India, those places where the church is currently flourishing and producing the bulk of vocations to the priesthood and religious life, even in the face of hardship and political resistance. Their faith has been honed in the struggle to rise out of poverty, to become educated, to be free to practice the faith.

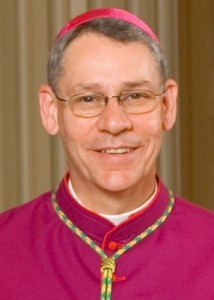

These priests are typically holy; they are serious confessors and at the altar they radiate joy — sometimes in mid-homily, they will burst into song. For them the faith is not a tired thing, and there is nothing better to be doing, than worship. For them, Catholicism is not — as Bishop Christopher Coyne so eloquently put it at his recent installation in Burlington, Vermont, “a church that is mourning itself.” More than once I have seen an African or Asian priest try to engage the benumbed assembly and seem puzzled at how retiring and reluctant we seem. “Why are you so shy?” One of them asks. From another, “I do not understand why you are not excited. Jesus is here!”

There is a regal-looking Nigerian priest who assists at a local parish; when Communion has ended and the Holy Eucharist is replaced within the Tabernacle, he will — his head bent in prayer — begin to sing, “Jesu…Jesu…Jesu…”

He sings it to “Amazing Grace”, and the congregation, which barely hums along with the music ministers, always joins him; always sings out. Some people even dare to harmonize with him.

At other times this priest may sing out, “O Sacrament most holy, O Sacrament divine…” and the congregation, again, joins in. Acapella. Three times. There is a spirit that overcomes the place, and a holy silence that follows what feels like a communal cleansing breath. For just a little while we are at peace.

Then we stand for the blessing, and the keyboard kicks in, and we do not join in song for the recessional.

It is the strangest thing. Materially, we have everything we need, spiritually, we are running on empty. These priests see it, and coming from impoverished lands, they can only shake their heads and keep plugging away, trying to get us excited, because Jesus is with us. And we don’t seem to know what that means.

Mother Teresa said the West suffered from a poverty much more debilitating than material poverty. The poor, she said (and I am paraphrasing) still know the value of a smile; they still know how to feel hopefulness, and gratitude; having nothing to hide behind, they tend to face the world full-on.

In the long-prosperous West where, as Peggy Noonan notes, we have little memory of how normal it used to be to only one one pair of shoes, we no longer comprehend those simple valuations.

We don’t know how to feel hopeful, because we wait for nothing; we have lost touch with gratitude, because we all make sure we’ve “got ours”. Materially, we have so much to hide behind (and within) that we needn’t face the world at all, if we’d rather not.

And that is partially why I described my diocese to someone, today, as “moribund” and “stagnant.” We are so materially satiated as to be disoriented; we are suffering a kind of spiritual paralysis. “What is the worth of a gold coin, compared to the dexterity of the hand that holds it,” ask a character in Terry Pratchett’s Making Money.

What is the good of amassing gold, when the spirit of its owner can neither move, nor shine?

This is why we, and the rest of the West, are the mission countries, the countries to which priests and religious are bringing the Gospel. We’re the missions that have heard the Name a million times, but have not yet had what Pope Benedict called the “necessary encounter”, have not yet met the Reality that is Christ Jesus.

We are the prosperous countries producing the fewest priests, partly because the world of things hails a siren call, party because “Western prosperity” insists that it requires families with 2.1 children, or less, and mostly because parents of small families tend not to start a conversation with, “honey, did you ever think consider that you might have a vocation besides careers and marriage?”

So, it’s an interesting paradox. We want people to not live in poverty; we work to bring them out of it. But how do we determine where the line is, where — having spiked the ball because we’ve scored the touch-down — we start believing that belief is for losers and poor folks?

Speaking of spiking the ball, when Jen sent me the recording of our session, I was hoping that it would contain her remarks leading into my intro, wherein Jen (a Texan!) was urging her listeners to watch the Super Bowl, and helpfully explained the game to those of her listeners who, like me, love baseball and understand its many nuances, but are rather baffled by football.

She said something like, “All you need to know is this: the team wants to move the ball ten yards, and if they get four tries to do it. That’s all you need to know, and you can enjoy the game.”

I loved it; succinct and to the point. Maybe this year, I’ll actually try to pay attention to more than the commercials!

Thanks, Jen!