A Baltimorean Defense of the Anthem, in Three Parts

Part The Third: Did Key Celebrate the Killing of Slaves?

In Part I we discussed how years of oppression by the British Empire — the impressment of American sailors, the seizure of American ships, the blockades of American ports — drove the young United States to declare war against the mightiest empire in the world.

In Part II we examined how Baltimore, specifically the shipyards producing the Baltimore Clipper style of privateer, came to be a prime target of the British, and why their failure to wipe out that “nest of pirates” was something worthy of celebration.

Now in Part III we’ll look at what sort of man Key was, and what he might have meant by the lines “No refuge could save the hireling and slave / From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave”.

As a Federalist, Francis Scott Key had been opposed to the war, but of course once it was joined he hoped for an American victory.[Taylor] He even served as a militia officer at the Battle of Bladensburg, the prelude to the British sack of D.C. Like most of the militia in that engagement, he took flight at the British approach; it may have been in an attempt at redemption that he volunteered to go into the lion’s den to negotiate the release of William Beanes.[Morley, 52-54]

He was, in the opinion of biographer Marc Leepson, “a really bad amateur poet…with one brilliant exception.”[McCauley]

And regarding that first verse, the one we all know, I agree. It’s worth noting that federal law (36 U.S. Code § 301) says that “The composition consisting of the words and music known as the Star-Spangled Banner is the national anthem” but does not actually specify what composition is known by that name — it seems to me that a sound argument could be made that this refers solely to that first verse. Key titled his poem “Defence of Fort McHenry”, and so there is some ambiguity there. When that law was adopted, just what composition was generally known as “The Star-Spangled Banner”? A infinite argument for mages.

But let us turn now to the stanza of Key’s poem that has caused such consternation of late:

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore

That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion,

A home and a country, should leave us no more?

Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps’ pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave:

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave,

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

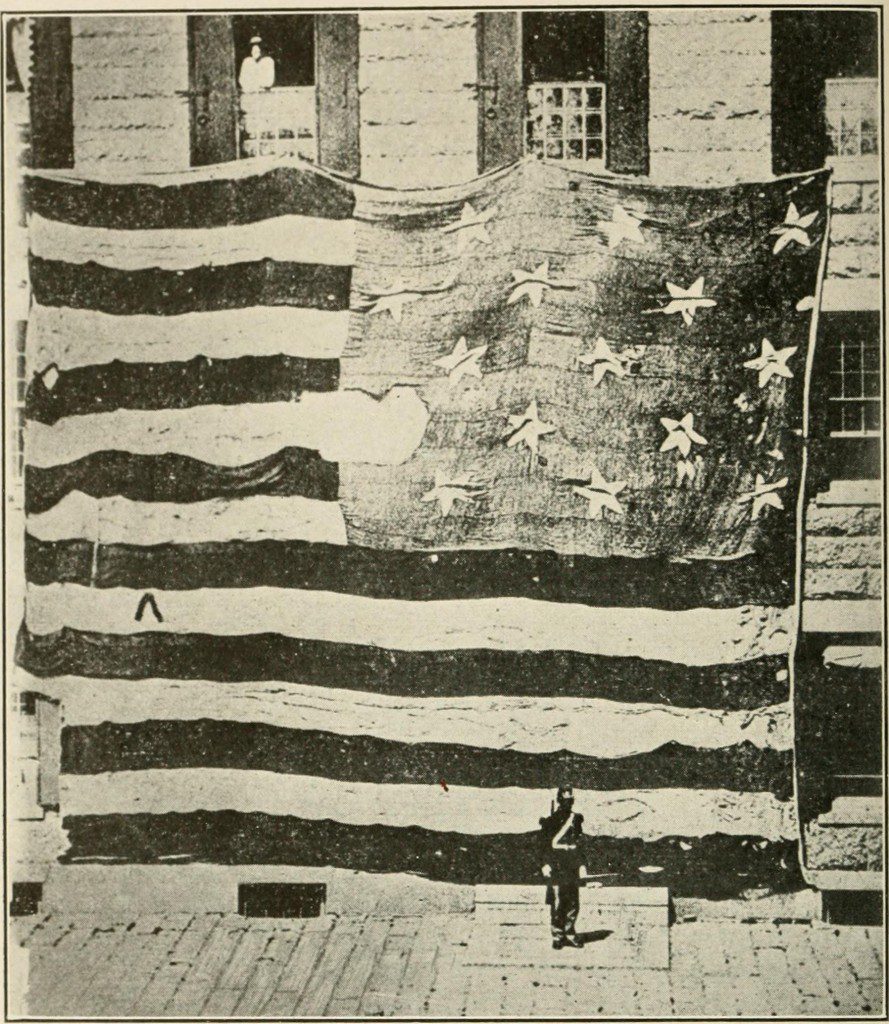

Much has been made of that reference to “the hireling and slave”. It has been pointed out that there were actually a few companies of escaped slaves, the “Colonial Marines”, fighting for the British.[Weiss] In a sense these men have been recently re-discovered, and their story deserves to be more widely told.

More than 4,000 enslaved people fled to the British and were freed;[“Black Sailors”] most had a hard future as poorly-treated refugees in Bermuda or Canada,[Weiss, Spray] but still were glad to be quit of their “masters”.[Oakes]

But for a few months, the British organized some of the escaped men into fighting companies. (A controversial move, given that Britain was still a slave-holding nation.)[Weiss] Knowing of the existence of these soldiers, at first glance it may seem that Key, a slaveholder[Leepson, 25], was referring to these ex-slave solders and glorifying their deaths.

But we are at the intersection of poetry and history here, and we ought to look carefully before closing the case.

First let’s consider the use of the word “slave”. Must it be literal, or could it be a general term of insult? Just as Baltimore had no actual “pirates”, despite the British insulting privateers as such.

As previously mentioned, “slave” was used this way in Elijah Parish’s widely-circulated “Babylon” sermon of 1811 to describe nations allied with France[Parish]. And it was used thus in several poems published in London in 1801, one praising the British soldier in comparison to those of “despots”:

To battle let despots compel the poor slave

His Country far him has no charms

But the voice of fair Freedom is heard by the brave

And calls her own Britons to arms[“Spirit”, 239]

and one insulting France as “a natural slave”:

What statesmen scheme and soldiers work

Whether the Pontiff or the Turk

Will e’er renew th expiring lease

Of Empire whether war or peace

Will best play off the Consul’s game

What fancy figures and what name

Half thinking sensual France a natural slave

On those ne’er broken chains her self forg’ d chains will grave; [“Spirit”, 386]

and another urging Britons to be courageous in the struggle with France:

Who will be a traitor knave

Who would fill a coward’s grave

Who so base as be a slave

Traitor coward turn and flee

Whom shall Gallic threats appal

Fly to glory’s sacred call

Freemen stand or freemen fall

Gallant Britons on with me[“Spirit”, 198]

It certainly seems possible that Key’s use of “slave” could be intended to insult British soldiers just as these poets used it to insult Britain’s enemies.

While Key was a slave-owner, he seems to have believed that slaves were due some humane treatment. (This is not to in any way justify slavery; it is to inquire whether he was, at the time, the sort of person who would rejoice at the death of slaves.) He actually spoke against the slave trade on some occasions, freed several of his slaves, and represented both slaves and free blacks in legal proceedings, including instances where slaves sued for their freedom.

He was even called (and pardon me for quoting the word) “The Nigger Lawyer”, and was credited by one writer with convincing him of the evils of slavery. On the other hand, he also represented slave owners fighting to keep their slaves, and did not free all of his own.[Leepson, 25-27] His record is complex. (Again, this is not to in any way justify or apologize for slavery, it is to attempt to put the man in the context of his time.)

It also strikes me that slaveholders in the late 18th and early 19th century often avoided the word “slave” or “slavery” in favor of various euphemisms. They spoke of the South’s “peculiar institution”, they put into the Constitution language about “other Persons” and the “Importation of such Persons” and “Person[s] held to Service or Labour.”

The actual titles of the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850 were “An Act respecting fugitives from justice, and persons escaping from the service of their masters,” (the same title for both acts, modulo capitalization) and neither act used the words “slave” or “slavery” anywhere in its text. [Statutes 1 302, Statutes 9 462]

It’s almost as if on some level they realized the shame of what they were doing. Given this habit I wonder if a slaveholder poet would be so bold as to refer directly to slaves — though this is just poetic speculation on my part.

We must also consider the slaves and free blacks who fought on the same side as Lieutenant Key. Black sailors made up about fifteen percent of the navy, and on some privateers made up the majority of the crew.[“Black Sailors”] William Williams, an escaped slave, was one of the few American soldiers fatally wounded at the bombardment of Fort McHenry. Many of the workers who built the naval ships and privateers were free blacks.[U.S. National Park Service] And slaves helped dig the hastily-build fortifications that protected Baltimore’s defenders.[ Iglehart]

It would be extraordinarily thick-headed for Key to not realize that both enslaved and free blacks were fighting on his side, even if a handful were among the opposition.

It would take a time machine to find out for sure what Key meant by “the hireling and slave.” But my judgment — possibly biased by Baltimorean pride, but I think still rooted in the facts — is that it was a poetic device to insult the British, and not a literal reference to those ex-slaves who were as determined to get their revenge on their American oppressors as the sailors of the U.S. were to get their revenge on their British ones.

And perhaps that’s the important lesson of history here, sadly relevant to our time: the harder the powerful press the powerless, the more the powerless will be willing to fight as soon as the opportunity arises.

References:

“Black Sailors and Soldiers in the War of 1812” PBS: The War of 1812. http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/black-soldier-and-sailors-war/

Iglehart, Ken. “Revenge of the Mongrels.” Baltimore Magazine. Jun 2012. http://www.baltimoremagazine.net/2012/6/1/200-years-the-war-of-1812

Leepson, Marc. What So Proudly We Hailed: Francis Scott Key, A Life. New Yorks: St. Martin’s Press, 2014.https://books.google.com/books?id=voPAAwAAQBAJ

McCauley, Mary Carole. “‘Star-Spangled Banner’ writer had complex record on race”. Baltimore Sun 26 Jul 2014. http://www.baltimoresun.com/entertainment/arts/bs-ae-key-legacy-20140726-story.html

Morley, Jefferson. Snow-Storm in August: The Struggle for American Freedom and Washington’s Race Riot of 1835 New York: Anchor Books, 2013. https://books.google.com/books?id=xVRQ8NsrP5MC

Oakes, James. Review of “The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832” by Alan Taylor. TruthDig. http://www.truthdig.com/arts_culture/item/the_internal_enemy_20131115

Parish, Elijah. A sermon preached at Byfield, on the annual fast, April 11, 1811 Newburyport, Mass. : E.W. Allen, 1811. http://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/general/VAC2143

Spray, W.A. The Blacks In New Brunswick. Human Relations Study Centre, St. Thomas University, 1972. http://atlanticportal.hil.unb.ca/acva/blackloyalists/en/context/articles/spray.pdf

The Spirit Of The Public Journals For 1801. London: James Ridgway, 1802. https://books.google.com/books?id=ibQPAAAAQAAJ

The Public Statutes At Large Of The United States of America, Vol 1. http://legislink.org/us/stat-1-302

The Statutes At Large And Treaties Of The United States of America, Vol 9. http://legislink.org/us/stat-9-462

Taylor, Alan. “The Battle for Baltimore,” History Now 31 (Spring 2012): Perspectives on America’s Wars. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. http://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/age-jefferson-and-madison/essays/battle-for-baltimore

U.S. National Park Service. “William Williams – Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine.” https://www.nps.gov/fomc/learn/historyculture/william-williams.htm

Weiss, John McNish. “The Corps of Colonial Marines: Black freedom fighters of the War of 1812.” 26 May 2015. http://www.mcnishandweiss.co.uk/history/colonialmarines.html

You can keep up with “The Zen Pagan” by subscribing via RSS or e-mail.

Please consider supporting this blog with a donation or purchase. The Zen Pagan Merch-o-rama has t-shirts, mugs, posters and prints, and stickers designed by yours truly.

If you do Facebook, you might choose to join a group on “Zen Paganism” I’ve set up there. And don’t forget to “like” Patheos Pagan and/or The Zen Pagan over there, too.