Today, technology is moving at a fast rate. Things that were science fiction 20 years ago are now experimental procedures. Many of these procedures, especially those around humans, raise ethical questions. We need to answer those ethical questions before we move forward. However, too often we ignore these questions or companies hire bioethicists simply to rubber stamp their procedures.

Even if we decide to go ahead with a procedure, it is important to discuss whether we should first. Hearing such concerns may give people pause before going through with it, even if the procedure is legal.

I want to summarize a recent article on the problems with the relationship between bioethics and science, followed by an application to genetics.

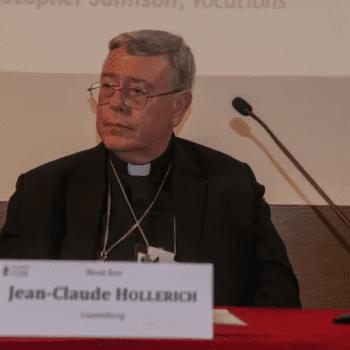

New Atlantis Article

Brendan P. Foht recently wrote an interesting article over at The New Atlantis on how bioethics is moving. I want to note a few things from it.

Induced Egg Cells

The article begins talking about the development of egg cells from adult stem cells.

Last September saw the announcement from scientists of the first manufacture of human egg cells in the lab. As surprising as it may sound, the creation in a lab of human sex cells using stem cells has been in the works for over a decade, with earlier experiments succeeding in deriving primordial germ cells, the cells of an early embryo that eventually give rise to sperm and egg cells. […]

The development nonetheless raises the question of whether it is a milestone on the road toward a world of dramatic technical powers over human reproduction — a world of cloning, designer babies, and children with four genetic parents. Indeed, a phalanx of prophets have for years been eagerly awaiting this very news.

This experiment making eggs from adult cells is a good example of where we aren’t so sure. Such induced human eggs might be useful for experiments as right now extracting human eggs for experiments is hard. Egg cells are part of the adult so experimenting on them in non-reproductive ways can be acceptable. Obviously, making human being in a petri dish is wrong, whatever the origin of the eggs. Also, the Church has ruled gene editing on such cells is immoral as it gets past down and may cause unseen issues down the line. But what happens if we take these eggs, place them in the woman’s fallopian tubes with the purpose of otherwise natural conception. Is that moral? I’m honestly not 100% sure. This may be an ethical way to solve a form of female infertility, but it may also be playing God.

Biotech Motivations

Foht then argues that part of the motivation for some scientists and bioethicists has a dark eugenic aspect.

A century after the heyday of eugenics, morally obtuse advocates for human enhancement, along with a collection of libertarians and assorted cranks, continue to hold out hope for its return in a redeemed form, one that is voluntary and medical rather than state-controlled and racist. While they posture as hard-nosed technocrats or bold advocates of reproductive freedom, the schemes they endorse are poorly thought through and plainly inspired by the crazed dreams of the original eugenics movement. Their shallow view of the moral problems posed by eugenic control — which for them begin and end at the possibility of state coercion — ignores the many ways that prejudice and social pressure can also shape the decisions of parents. And their outlook offers no sense whatsoever that the transformation of procreation into a manufacturing process, subject to strict quality control, might undermine the unconditional love we expect and value between parents and their children.

I don’t think this is the only motivation that scientists and ethicists have. Nonetheless, I’ve seen a lot of discussion that tends in this direction or implies this.

The attitudes of bioethicists often seem like benign neglect to Foht where they just acquiesce to the scientists.

There has been plenty of ethical commentary on the implications of stem cell–derived gametes over the past ten years. But looking at how ethicists have in fact reflected on the use of stem cell–derived gametes, we can see some of the recurring themes in discussions of reproductive technology: schemes for human enhancement that are plainly influenced by the old-line eugenics movement, updated versions of eugenics as an ideology of parental choice and technocratic management, and contrarian defenses of morally repugnant reproductive arrangements in the name of autonomy. We find ethicists and scientists acting with what Paul Ramsey characterized as the “frivolous conscience” — raising “ethical” questions without taking seriously the possibility that the answer to those questions would be that a technological development or line of research is wrong.

This is a problem like noted in the introduction: secular bioethics doesn’t always work on solid principles but often changes principles to approve the new biotech.

Just Yuck Factor

Later in the article, Foht describes how some deride moral objections.

In a 2017 paper on the ethics of stem cell–derived gametes, Annelien L. Bredenoord and Insoo Hyun described multiplex parenting [i.e. children with 3 or more parents] as “the most paradigm-shifting use of stem cell–derived gametes.” They acknowledge that such applications “will inevitably trigger ‘this is unnatural’ type of objections, or appeals on the ‘yuck factor,’” before noting that such objections “have been proven flawed and morally prejudiced in earlier discussions.”

What is important to Bredenoord and Hyun, however, is that we avoid calling stem cell–derived gametes “artificial” or “synthetic,” since “these labels may give the pejorative impression that stem cell–derived gametes are ethically inferior to other types of ART [assisted reproductive technologies].” To make sure that multiplex parenting is implemented responsibly, it will be necessary to conduct “sociological research to evaluate the long-term welfare of children born through these techniques.”

It is hard to know what to make of this kind of defense of a morally repellent way of making babies, except to speculate that these ethicists have become so committed to opposing Leon Even the way the authors talk about how multiplex parenthood might “trigger” objections from ordinary people makes it sound like they are more interested in trolling than in serious moral analysis. What makes this kind of reaction especially unfortunate is that these two ethicists occupy relatively important positions in the field of stem cell research: Both are members of the International Society for Stem Cell Research’s ethics committee, for which Hyun was even once the chairman.

This is a serious issue. Moral repugnance is not the be-all and end-all of morality but it should be a part. Reducing all the arguments against a practice to such moral repugnance shows a rather twisted attitude on the part of the bioethicists who are not even willing to admit serious objections exist.

Going Forward

Foht concludes his piece with a suggestion and a warning.

There has been too little political will to seriously regulate and restrict the development of reproductive technologies. For too long the moral problems raised by them have been left to professionals with warped priorities… The community of professional bioethicists may find such laws ill-advised or extreme, but given their morally frivolous record, there is little reason to trust them to provide meaningful oversight for these technologies — and so direct prohibitions are necessary.

That is a fundamental issue. Who has a voice at the table? If it is only the scientists, they will inevitably endorse almost every new technology due to twisted incentives.

Bioethics and Genetics

So let’s take a less extreme bioethical concern: genetic testing. Right now, if parents opt for IVF, a lot of genetic tests are often done to kill off 8-cell babies with certain conditions. To do this test, one of the 8 original cells is removed. Besides the issues with IVF, I’m not sure if removing a cell that early on has unforeseen negative effects.

Now a company called Genomic Prediction is going further and testing a whole bunch of spots to eliminate low IQ babies. I wrote about the ethical problems with this back in November, however, there has been little written on the ethics of this. One of the few pieces to address the ethics outside of publications specializing in genetics or cutting edge science was in The Guardian. Philip Ball, a science writer not an ethicist, compared such tests to common Down’s syndrome tests.

Bear in mind that already we permit, even in the UK, prenatal screening for Down’s syndrome, a disability that produces low to moderate intellectual disability. It’s not easy to make a moral or philosophical case that the screening offered by Genomic Prediction for low IQ is any different. There may be more uncertainty but, given not all IVF embryos will be implanted anyway, can we object to tipping the scales? And how can we condone efforts to improve your child’s intelligence after birth but not before?

Mr. Ball, let me explain, the result of this test is to kill the dumb child while keeping the smart child. We don’t have two kids, wait till 3rd grade and see who is academically performing better then kill the less brilliant. Although obviously, the kids are smaller and less developed when you do this test, that is essentially what happens when you have IQ selective abortion.

In the same article, Ball notes that at least in the UK, such pre-implantation genetic diagnosis is only legal for rare conditions the parents are known carriers of. However, it seems a rather arbitrary diving line rather than saying no killing people because of their DNA.

Pope Francis spoke out about procedures like this a year ago. As CNA reported:

“I’ve heard that it’s fashionable, or at least usual, that when in the first few months of pregnancy they do studies to see if the child is healthy or has something, the first offer is: let’s send it away,” the pope said June 16, referring to the trend of aborting sick or disabled children.

This, he said, is “the murder of children…to get a peaceful life an innocent [person] is sent away…We do the same as the Nazis to maintain the purity of the race, but with white gloves.”

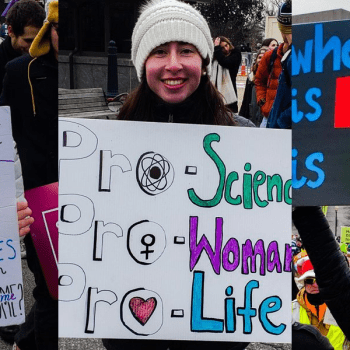

Some Attempts at a Solution

Right now, companies will only fund bioethicists who greenlight their projects; governments tend to prefer a hands-off approach and if they hire bioethicists, they often try to get those who are explicitly secular. However, explicitly secular involves a bias that will tend towards approving all kinds of questionable procedures. On the other hand, the Christian churches are often strapped for cash and do not fund bioethics extensively.

However, if we want to avoid a future as envisioned in dystopian works like Gattaca or Brave New World, we need to fund bioethicists to both do the research and share it with the public to affect public opinion. The best way to stop such crazy procedures from becoming common is to change public opinion so politicians follow suit. Right now, very few are employed in think tanks, public policy, church bodies, etc. that have a view compatible with the Christian vision of human dignity. If we don’t change this, technology will continue to outstrip the ability of those of us with more concern for human dignity which makes us more cautious about bioethical development.

We also need to work on fighting the secular forces opposing us, not jet caught up in smaller issues where we might, and often do, disagree. For example, it isn’t clear if Catholics can morally adopt frozen embryos created by IVF or whether this is immoral; this is relevant but the bigger question is doing what we can to stop having millions of tiny frozen humans.

The few that are employed are often focused on reaching those inside religion. Honestly given the numbers and the amount of influence others have on religious members this isn’t a bad tactic: as at least these people will have a proper bioethical stance. However, we need to reach beyond our segment if we want to have a strong influence on public policy.

Technology is going fast and the only way to make sure society doesn’t embrace the attitude of “We should because we can” is to put more effort into bioethics from a Catholic and Christian perspective.

If you like content like this, please support me on Patreon.