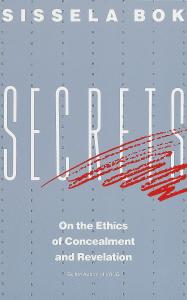

As some of you may know, my current full-time responsibility is writing a doctoral thesis on the right to privacy. To this end, I have read a bunch of secular thinkers on what privacy means. Recently, I was reading Secrets: On the Ethics of Concealment and Revelation by Sissela Bok. She has a chapter on the idea of confessing wrongs. In this chapter, she has a few things about confessing to other persons that are valuable for the sacrament, not just confession between human persons.

I want to share four insights I found in this chapter. I will leave them with minimal commentary. Bok is a retired philosopher and ethicist of the continental school. Both of her parents (Gunnar Myrdal and Alva Myrdal) won noble prizes: talk about a tough standard to live up to.

Confess Only Sins

She notes the need to confess only what one has power over (pg. 76-77):

People confess only to previously concealed matters over which it is (or has been) possible, at least in principle, to exert some control, or for which they acknowledge at least shared responsibility. Thus they may confess to incest or to child abuse, but not to having unwittingly transmitted polio; they may confess to religious backsliding, but not to loss of memory. But they also seek support against forces they may regard as too strong to combat alone – addiction, perhaps, or weakness of will, or supernatural powers of evil. By confessing, they often hope to align themselves with communal or sacred forces that will help in this battle. Because they accept responsibility and seek such assistance, they are in a position to offer some assurance of efforts to change: efforts great enough to affect their entire way of life, perhaps also to allow them to transcend their old selves and attain forgiveness or salvation in a future lite. The change may be from deviance to normalcy, from wrong to right, from ignorance about the self to insight.

In this way, confession may serve as a means for transforming one’s life. It may bring new insight and a chance to re-create oneself. This cannot easily be achieved through introspection alone. To seek out a confessor is, then, to look for someone who can share one’s burdens, interpret one’s revelations, and show the path to release. Confessing may be a call for intervention and for help in reaching through to the layers of secrecy sensed in oneself or in the authority one confronts. Thus Dietrich Bonhoeffer sees confession as a breakthrough to fellowship and community. By making manifest ‘all that is secret and hidden,’ confession brings the sin into the light.

Confession strengthens resolve for many, and thus serves as an added control for those who are not certain that they will be capable of keeping the temptations of their past lives subdued. They see their lives as a battleground between great forces, and the confessor as an ally in the battle. Naming the temptations and the hostile forces may give strength to resist them. So long as these forces are nameless, they remain blurred and shadowy. Once named, they are forced into the light, compelled to take on an identity. Perhaps they may then be ‘done to death,’ as Origen put it when describing the need to bring sins into the open:

“For if we do this and reveal our sins not only to God but also to those who can heal our wounds and sins, our wickedness will be wiped out by him who says ‘I will wipe out your wickedness like a cloud.'”

The subquote is attributed to Origen, Homiliae in Lucam, in Bettenson, ed., Early Christian Fathers, 253.

Modern Psychology Takes from Confession

Bok notes how modern secular practise takes from confessin (pg. 79):

Like the earlier religious practices, current secular ones focus intensive and detailed probing on the individual’s experience present and past, and especially on sexuality in all its stages and manifestations, seeking thereby to alleviate guilt and to bring about a personal transformation. Just as religious confessors have urged those in their charge not to leave out of account a single sin or even a sinful thought, so analysts have stressed the basic rule of analysis: that not a single secret, no matter how seemingly irrelevant, be held back. Without such complete openness, each of the traditions has held, it might not be possible to help revealers overcome their suffering. Without it, the desired freedom and transformation would be out of reach.

Secrets Fester in the Soul

Sissela Bok notes that maintaining secrets and excessive probing can both be dangerous for the soul (pg. 82):

Secrets left hidden will continue to fester, it holds, unless exposed. Patients risk nothing in exposing harmless secrets, and stand to benefit greatly by bringing harmful ones into the open: as a result, they have nothing to lose and much to gain by the fullest possible disclosure. But such an assumption is far from indisputable. I have pointed in earlier chapters to injuries that can stem from indiscriminate self-revelation. They should at the very least be taken into account in weighing how deeply to probe. […]

When the probing for secrets is not only needlessly invasive but also carried out by coercive means, self-deception may be invoked as added justification. Listeners who threaten or otherwise force people to confess may argue that those who protest want, at the same time, to be helped, so that coercing them only seems to go counter to their will, no matter how strong their objections; for there is that other, deceived part or their selves that in fact desires help in overriding the protests.

The Value of Seal of Confession

She also notes that without the seal, confession can be manipulative if not kept under a professional or sacramental seal (pg. 84):

When the probing for secrets is not only needlessly invasive but also carried out by coercive means, self-deception may be invoked as added justification. Listeners who threaten or otherwise force people to confess may argue that those who protest want, at the same time, to be helped, so that coercing them only seems to go counter to their will, no matter how strong their objections; for there is that other, deceived part or their selves that in fact desires help in overriding the protests. […]

Self-revelation becomes manipulative when the unspoken aim is to secure from others some response they would otherwise restrain: confidences in return, or a bond that can be exploited, or some form of cooptation. Seduction is the aim of much self-disclosure of a manipulative nature.

Conclusion

This is obviously just one secular ethicist, but Bok is a pretty “mainstream” voice of secular ethics. Obviously, the greatest value of confession is the forgiveness of sins through contrition and absolution which re-opens the gates of heaven to us. Nonetheless, I think it’s worth noting the other positive aspects of confession. Confession is also helpful psychologically. God made us for the sacraments! The sacraments are the fullest and truest part of human life with the rest just pointing to them.

Note: If you appreciated this, please support me on Patreon.