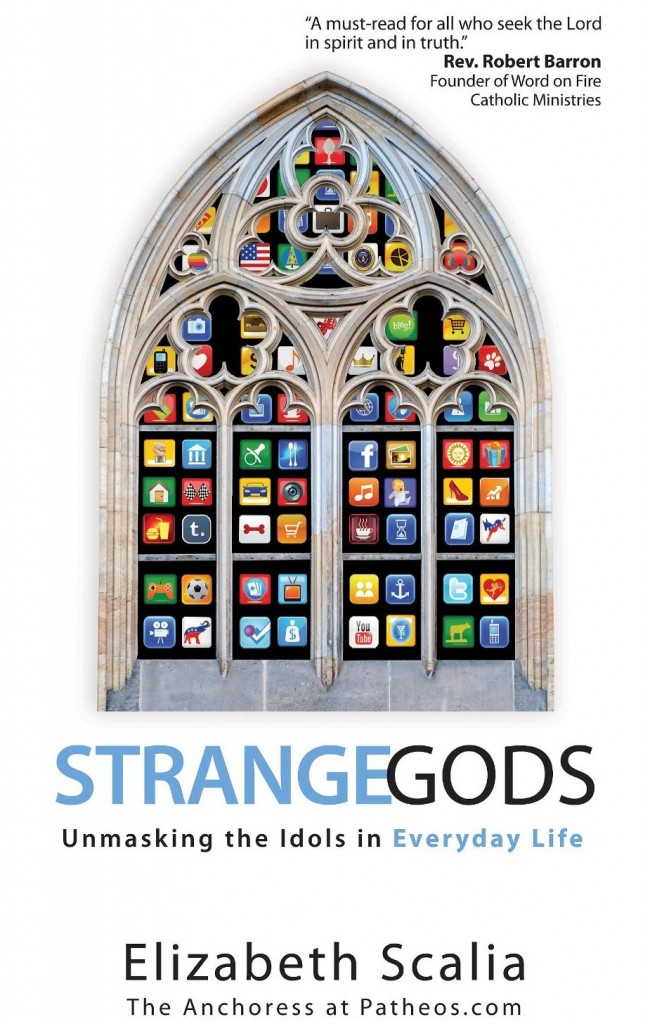

In Strange Gods: Unmasking the Idols in Everyday Life, Elizabeth Scalia has a simple definition of an idol. In the decalogue, we are warned by God to have no other/foreign/strange gods before Him. So, in our modern age, Scalia points out, our idols are less likely to be something like, say a giant golden calf that give burt offerings, and more likely to be letting Reddit usurp our prayer time. An idol doesn’t have to be worshiped to impose itself between us and God.

But what would it be like to face God, with nothing between us and Him? It’s sounds terrifying, akin to the staring at the sun sect that appears in “The Eye of Apollo” from Chesterton’s The Innocence of Father Brown. Or maybe it’s like the experience of Frodo, when he cried out to Sam, “I am naked in the dark, Sam, there is no veil between me and the wheel of fire! I begin to see it even with my waking eyes.”

The technically-good horror of facing God directly is why I’ve always liked this quotation from Diane Duane’s A Wizard Alone:

“Virtue,” he said. “The real thing. It’s not some kind of cuddly teddy bear you can keep on the shelf until you need a hug. It’s dangerous, which is why it makes people so nervous. Virtue has its own agenda, and believe me, it’s not always yours. The word itself means strength, power. And when it gets loose, you’d better watch out.”

“Something bad might happen…”

“Impossible. But possibly something painful”

I’m someone who tends to take about fifteen to twenty minutes to get into a swimming pool — wading in inch by inch, with copious wincing. When I was in kindergarten, and got to play on the monkey bars for the first time, I hung from just the first rung and practiced dangling and swinging back to the platform and getting off. Once I could do that calmly, I dropped from the first bar about a dozen times until I was sure I falling wasn’t too bad. My sense of safety depended on my sense of control. That’s not an option in Catholicism.

I have a wunderkammer of idols, but I notice that a fair amount are an attempt to draw some kind of screen between myself and God or other people (same difference, after all “to love another person is to see the face of God“). It’s easy to interact as a persona, rather than a person. Stephen Colbert-in-character is an extreme example, but it’s always tempting to exaggerate flaws and foibles to the point where they’re comical instead of vulnerabilities.

I’ve been trying to be more careful about running jokes and Homeric epithets since I caught myself using one as a crutch. After seeing The Mikado, I stole one of the phrases (“in my artless Japanese way”) to use as an excuse when I was socially maladroit. Instead of being callous or careless, I was being amusingly strange. But it would be better to be sincere, regretful, and have the ability to grow — to not treat that weakness as an essential distinguishing trait.

In the secular world, you see this point made by many disability activists (a person without the use of her legs, not a paraplegic). In the autistic and Deaf communities, this kind of language becomes controversial precisely because there’s a disagreement about whether their differences are incidental or essential to identity. We can all stand to be a little more thoughtful about the names and identities we hold on to. Paul Graham counsels people to “Keep your identity small” and view as few things as possible as inviolate.

The trouble is, the part I should hold on to “adopted daughter of God” is so much vaguer than the identities I’d like to hand on to: New Yorker (with attendant walking and speaking speed), Sondheim nerd, brusque/efficient, bad at small talk, uninterested in physical activities, kludger/engineer, etc.

But if I only hold on to what I can grasp, I’m choosing to remain small and isolated. To submit to God, I have to be ok with not having mastery.