Happy Feast of All Saints!

This week’s quick takes theme is transposition, and there are few people as in love with stories and patterns as Douglas Hofstadter, author of Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid and his recent work on analogy: Surfaces and Essences. In a recent interview with The Atlantic, he talked about what he sees as the heart of human intelligence:

Cognition is recognition,” he likes to say. He describes “seeing as” as the essential cognitive act: you see some lines as “an A,” you see a hunk of wood as “a table,” you see a meeting as “an emperor-has-no-clothes situation” and a friend’s pouting as “sour grapes” and a young man’s style as “hipsterish” and on and on ceaselessly throughout your day. That’s what it means to understand. But how does understanding work? For three decades, Hofstadter and his students have been trying to find out, trying to build “computer models of the fundamental mechanisms of thought.

And a tumblr user had an unexpected thrill of recognition when ze discovered that “the addition of “Harry” to almost any Plato quote makes it seem legitimately like a nugget of wisdom out of the mouth of Albus Dumbledore.” Here are some of the blogger’s alterations:

Death is not the worst that can happen to men, Harry.”

“Harry, good actions give strength to ourselves and inspire good actions in others.”

“He who commits injustice is ever made more wretched than he who suffers it, Harry.”

Note, this does not work for Nietzsche. A few of my own attempts:

“The true man wants two things, Harry: danger and play. For that reason he wants woman, as the most dangerous plaything.”

“Harry, it is impossible to suffer without making someone pay for it; every complaint already contains revenge.”

“Fear is the mother of morality, Harry.”

Fifty points to the house of anyone who works one of these into their fanfic.

Fun fact: when my college debate group was coming up dry on debate topics, we’d try just stealing Nietzsche quotes. Turns out “Resolved: Christianity gave Eros Poison to drink” is a pretty terrible choice but some of the others turned out better.

A writer at The New Inquiry did an amusing job of reinterpretation when he decided to review the new DSM as a work of dystopian literature.

This is not to say that there is no setting, no plot, and no characterization. These elements are woven into the encyclopedia-form with extraordinary subtlety. The setting of the novel isn’t a physical landscape but a conceptual one. Unusually for what purports to be a dictionary of madness, the story proper begins with a discussion of neurological impairments: autism, Rett’s disorder, “intellectual disability”. The scene this prologue sets is one of a profoundly bleak view of human beings; one in which we hobble across an empty field, crippled by blind and mechanical forces whose workings are entirely beyond any understanding. This vision of humanity’s predicament has echoes of Samuel Beckett at some of his more nihilistic moments – except that Beckett allows his tramps to speak for themselves, and when they do they’re often quite cheerful. The sufferers of DSM-5, meanwhile, have no voice; they’re only interrogated by a pitiless system of categorizations with no ability to speak back. As you read, you slowly grow aware that the book’s real object of fascination isn’t the various sicknesses described in its pages, but the sickness inherent in their arrangement.

Who, after all, would want to compile an exhaustive list of mental illnesses? The opening passages of DSM-5 give us a long history of the purported previous editions of the book and the endless revisions and fine-tunings that have gone into the work. This mad project is clearly something that its authors are fixated on to a somewhat unreasonable extent. In a retrospectively predictable ironic twist, this precise tendency is outlined in the book itself. The entry for obsessive-compulsive disorder with poor insight describes this taxonomical obsession in deadpan tones: “repetitive behavior, the goal of which is […] to prevent some dreaded event or situation.” Our narrator seems to believe that by compiling an exhaustive list of everything that might go askew in the human mind, this wrong state might somehow be overcome or averted.

And, in an even more delightful transposition, after the husband and wife team at DarwinCatholic were piqued by an update of Sense and Sensibility, they started thinking about how to make the plot hold up in modern times, especially when engagements aren’t really binding. I love what they came up with:

Elinor Dashwood meets Edward Ferrar (the brother of John Dashwood’s wife) and they are attracted to one another, but for reasons that do not become clear for a while he makes no move to enter into a relationship with her. In the book, it is eventually revealed that this is because he long ago entered into a secret engagement with Lucy Steele. He knows that if he admits to the engagement, he’ll be disowned by his mother which will impoverish him, and he’s since fallen out of love with her (and realizes that she doesn’t really love him) but he’s too honorable to break off the engagement with her (because, the nature of marriage at the time having strong financial aspects, Lucy has staked her economic future on this offer), so he’s unavailable but can’t talk about it.

[…]

I wanted to come up with a reason why Edward could not ethically enter into a relationship with Elinor, and also couldn’t tell her why. My solution is that Edward is a lawyer. He’s been hired by Lucy Steele to investigate a possible legal action against the Dashwood company (intellectual property or something else fairly secrecy related such as that.) Edward has come to think that Lucy’s case has no merit, but he’s convinced that he’d be accused of a conflict of interest if he started a personal relationship with Elinor while still representing Lucy, while he’s afraid that if he dropped Lucy and started a relationship with Elinor, she’d accuse him of violating confidentiality. Further, because of the nature of the case, he would compromise Lucy’s case if he told Elinor the nature of his entanglement.

Meanwhile, in stranger updating Austen news, someone is kickstartering an Austen MMORPG.

Found via i09, a beautiful video from a RISD animation student on why she is passionately in love with physics.

And as we untangle the stories around us, and the ways they shape our models of the world, I feel compelled to link to an NPR story that’s shooting near the top of my list of favorite experiments people perform on children.

To study the origins of belief in fantastical cultural creations, three researchers at the University of Texas at Austin — Jacqueline Woolley, Elizabeth Boerger and Arthur Markman — made up their very own fictional being: the Candy Witch. In a clever and well-known study, they tested whether and how preschool-aged children would come to believe she was real.

The Candy Witch was introduced to children at their childcare center just before Halloween. Children learned about the Candy Witch — depicted as a rosy-cheeked blonde woman (i.e., a poor candidate for Huffington Post’s recent enumeration of the 13 most badass witches) — without explicitly being told she was real or pretend. Instead, a teacher explained that when she’s invited to do so, the Candy Witch goes to children’s houses on Halloween night and swaps some of their Halloween candy for a toy. The children later participated in an activity to make a Candy Witch puppet, the sort of project that children might complete around Easter (for the Easter Bunny) or Christmas (for Santa Claus).

Importantly, the researchers also varied whether the children received more direct evidence to support the existence of the Candy Witch. About half the children “overheard” their parents call the Candy Witch by phone on Halloween to make arrangements, and those same children found that the next morning, some of their candy had been swapped for a toy.

Of key interest were whether children would come to believe in the Candy Witch at all, whether their “gullibility” would decrease with age, and whether they’d be more likely to believe the Candy Witch was real after experiencing a candy-swap firsthand.

Note, this means that parents were in cahoots with the researchers and were randomized into needing to do upkeep on an additional holiday lie. Perhaps they liked having cover for eating their children’s candy once the tykes were asleep.

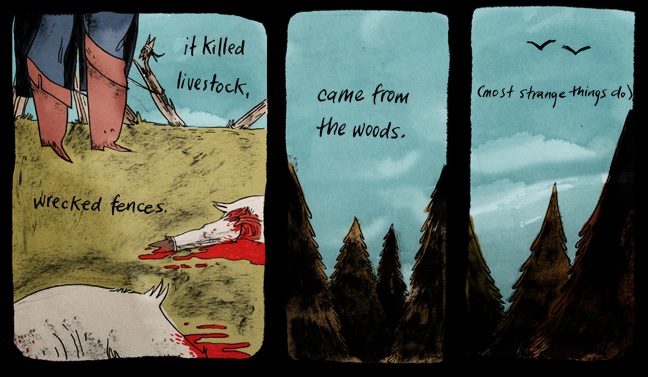

And finally, if you didn’t get enough scares on Halloween, I have two horror short stories drawn by Emily Carroll to recommend to you. The first, “His Face All Red” is creepy enough, but “Out of Skin” is profoundly grotesque, so be advised.

For more Quick Takes, visit Conversion Diary!