I’d never read or seen Coriolanus before a group of friends and I went out to see Tom Hiddleston as the eponymous lead in an NT Live broadcast. During intermission, one of my friends leaned across our block of seats to say, “I’ve guess this is the methadone to my House of Cards addiction.”

In Coriolanus, the title character is a great general, but flounders when his friends try to elevate him as a Roman Consul. His apparent arrogance and disdain for the ordinary people of Rome, who he would prefer to serve only in battle, causes the tribunes of the Populares to seize on his tactless, unfiltered contempt to build up their own support and expel him from the city. Their scheming had something of the same character as Frank Underwood’s soliloquies, but, in this production, our sympathies weren’t expected to be with the master manipulators, but the artless idealist.

But Kate Havard of First Things thinks it’s a mistake to grant Coriolanus the voices and praise the city denied him. She writes:

Coriolanus didn’t die for Rome’s sins. But there’s a moment early on in Josie Rourke’s production of Coriolanus that might make you wonder if she thinks he did. In it, the Romans take their bloodied hero (played by Tom Hiddleston), crown him with a thorny garland, and hoist him up above them. He looks rather Christ-like, sitting up there, even if the Christ imagery doesn’t make much sense…

Suffice it to say: Coriolanus probably ranks rock bottom on a list of “Shakespeare’s Most Christ-like Heroes.” He hates most people. He has no real allegiance to anything other than himself, quickly turning on the Romans. He is willing to burn his city to the ground, with his mother, wife, and child inside it. He is not any kind of savior at all….

Coriolanus may have little loyalty to Rome, but he is the perfect Roman, and in this play, that means he is utterly self-denying. A thoughtful audience will be as impressed by Coriolanus’ martial virtues as they are aware that those virtues come with a cost. When Coriolanus is portrayed limping around in pain or embracing his family or weeping, his decision to march on Rome becomes inexplicable. Rourke won’t let him be the creature Shakespeare made: beautiful and terrible and heartless. She insists that he must have a heart. For if Coriolanus is so great—and he is—mustn’t he also be good, as we commonly understand it?

Not in ancient Rome: What makes Coriolanus the greatest man in Rome makes him the greatest threat to Rome. His strength makes attachment to the city unnecessary. Rourke tries to humanize Coriolanus, but in doing so she makes him an easily manipulated strongman without any of the greatness.

Go on, read the whole thing, it’s excellent. I’ll wait.

But I can’t quite bring myself to agree with Kate’s complaint. I disagree with her claim that Coriolanus “has no real allegiance to anything other than himself” as much as I disagree with the angry citizen in the opening scene who says that, although Coriolanus appears to serve the city, “He pays himself with being proud.” But this production did earn the title of Kate’s essay “Coriolanus Alone” by undercutting the relationships would show that Coriolanus does have a heartfelt allegiance to honor.

The text of the play tells us that Coriolanus and his enemy Aufidius share a brotherhood of warriors. Both are swift to praise the other, even as they both long for the opportunity to confront and conquer each other in battle. When Coriolanus is exiled, he seeks out Aufidius and offers him his loyalty or his life, whichever Aufidius prefers to take. The camp of his enemy is the only place Coriolanus is certain he can live out his vocation to war honestly.

But it all goes awry with the bizarrely erotic staging of Aufidius’s welcome. He paws at Coriolanus’s head, kisses him passionately, and clownishly can’t keep his hands off him. The show isn’t presenting us with a noble vision of homosocial love — Coriolanus looks perplexed, and, in the background of the scene, Aufidius’s servants are openly contemptuous or confused by their master’s behavior. This directorial choice robs the scene of the character of a homecoming and means that Aufidius and Coriolanus are never completely united as two men with a shared love.

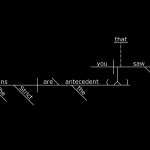

That’s how we wind up with a Coriolanus alone, since, with this diminution of Aufidius, no one remaining in the cast has a love of something greater than themselves, and Coriolanus, isolated by his devotion, draws our sympathies. The plotting Tribunes are openly contemptuous of the people they serve, expertly manipulating them (We will be there before the stream o’ the people; And this shall seem, as partly ’tis, their own,Which we have goaded onward), Coriolanus’s friend Menenius (played by Sherlock‘s Mark Gatiss) wins the love of the audience with his witty putdowns of all the other characters, and Coriolanus’s mother, at first seeming a slave to duty, like her son, tells him to put aside his honor in order to win glory as a consul. They have skills, but seem indifferent about to what use those skills will be put.

As such, Coriolanus emerges as the only character to cling to some kind of vocation. Coriolanus dies in a tragedy of his own making, but it is tragic because we can more easily imagine an appropriate use for his gifts than for the those of the rest of the company. He has chosen a telos that isn’t worthy of the fervor with which he pursues it, but he earns our sympathy, because we would long to see that devotion and dying to self devoted to some other good.

DarwinCatholic is praying a novena for Ordering Lives Wisely by St. Thomas Aquinas, that will end on Ash Wednesday. If you’d like to join her and me, you can find the prayers here.