In 2014, I’m reading and blogging through Pope Francis/Cardinal Bergoglio’s Open Mind, Faithful Heart: Reflections on Following Jesus. Every Monday, I’ll be writing about the next meditation in the book, so you’re welcome to peruse them all and/or read along.

In this week’s selection from Open Mind, Faithful Heart, Pope Francis talks about how we can discern God’s will for us in the great sweeps of history and the small, internal movements of our own hearts:

As I said before, if we want our lives to become part of God’s manifestation, they must be inserted into human history. What is more, they must be reinterpreted in light of the great events of this history… If we were to understand our own lives or the life of the institution to which we belong outside this perspective, then we would be expressing merely human attitudes. Our judgements would be based on worldly criteria, which inevitably fall outside the shadow of the mystery of the cross. In the Gospel narratives of Jesus’ birth, we find him revealing himself to the simple folk, the shepherds, the humble sages (the Magi), The preferences of God do not incline toward social elites or the worldly wise, but only toward the lowly, simple folk who insert themselves into history as servants of the only “Servant,” the one who gives meaning to the whole of our journey.

Saint Ignatius, at the end of the Spiritual Exercises, proposes that we “call back into our memory the gifts we have received–creation, redemption, and other particular gifts–so as to ponder with deep affection how much God has done for us… Doing this means searching out in our own lives the traces of God, the God.

The part I found most striking about this passage is that, when Pope Francis talks about history, he clearly does not mean only the people who wind up in the history books. The complaint of Mrs. Lintott, from The History Boys would not be foreign to him (“History is a commentary on the various and continuing incapabilities of men. What is history? History is women following behind with the bucket.”).

When we look at what the world records, it is a litany of our insufficiencies and attempts to manage them, with a great deal of the work being done by people whose names are not recorded. There’s no reason we need to become one of the people whose names get written down in order to be inserted into human history, and yet a desire for higher stakes seems to crop up sometimes in Catholicism (to wit, the oft-cited line from Cardinal Francis George: “I expect to die in bed, my successor will die in prison and his successor will die a martyr in the public square”).

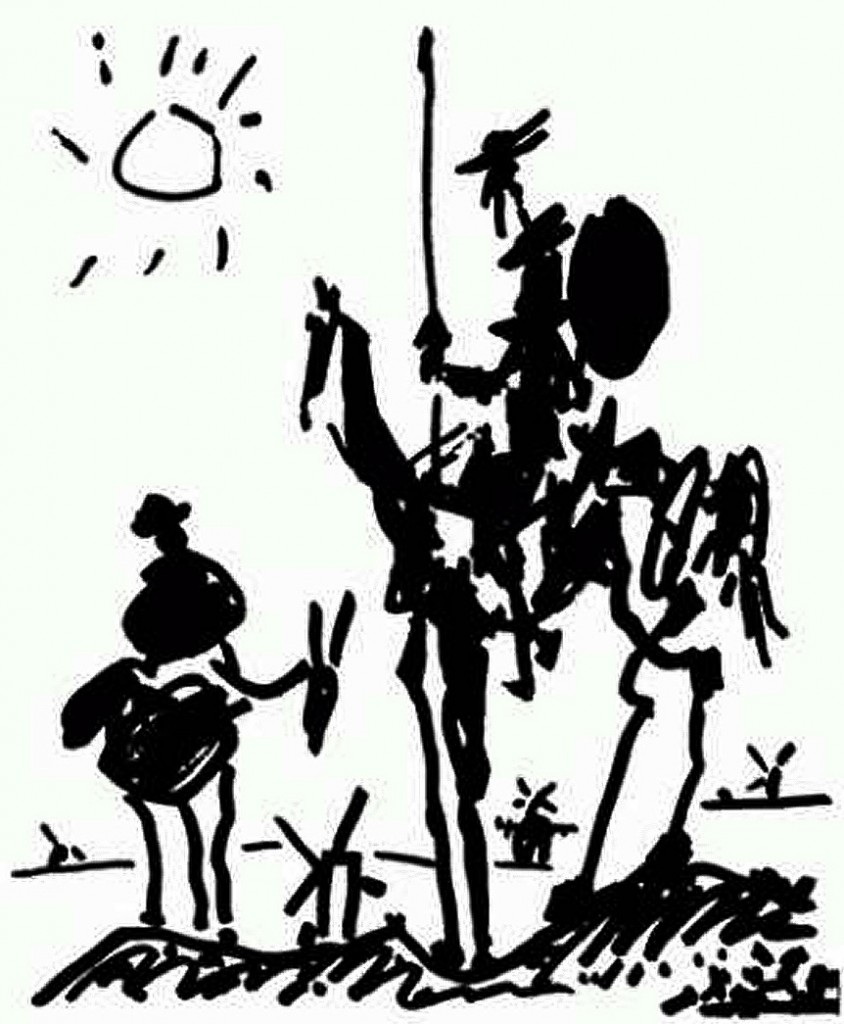

Such a life would certainly rate mention in the worldly history books, but that recognition ought to be irrelevant to a Christian trying to live righteously. There’s enough tumult and strife in one heart, or one community to satisfy a hundred Don Quixote’s longing for noble battle.