“This mind is Buddha” is one of the most evocative teachings of our Zen school. It is a “teaching,” not a philosophical assertion or a faith statement, but rather a description of enlightening experience. Dōgen cites “This mind is Buddha” teaching in several fascicles in the Shobogenzo, eight dharma discourses in the Eiheikoroku, and also in his Shinji Shobogenzo (1).

In this post, I will explore Dōgen’s working through of this kōan in relationship to enlightenment and just sitting. And along the way, I’ll offer some reflections on post-enlightenment practice, the vow to free all beings, and how that vow plays out in Dōgen’s and Hakuin’s expressions of Zen.

And just for fun, I’ll work with a recently published translation of Dōgen’s Eihei Koroku (2) by Thomas Cleary (3). You will find it free on Amazon, along with some other texts Cleary has self-published, like the Empty Valley, an important kōan text. I will comment too, mostly on Dōgen’s comments, and so have the Dōgen text italicized. I’ve also added some headings to help organize the text for you, the reader.

The main case

[Dōgen said,] The correct method accurately communicated from Buddha to Buddha, master to master, is just sitting.

My late teacher Rujing instructed a congregation, “Do you all know the story of Zen master Dàméi (4) calling on Great Master Mǎzǔ (5)? He asked Mǎzǔ, ‘What is Buddha?’ Mǎzǔ said, ‘Mind itself is Buddha.’

He thereupon bowed and left, and went up to the summit of Dàméi mountain, where he ate pine pollen and wore lotus leaves, spending the rest of his life sitting meditating day and night, nearly thirty years. He was not known to kings or ministers, and did not go to invitations of patrons or donors. This is an excellent example of the way of Buddhas.”

Dōgen begins with a clear and characteristic thesis, “the correct method … is just sitting.” And to show that it has been transmitted from “Buddha to Buddha, master to master” he quotes his own master, Rujing, who serves as Dōgen’s backdrop, adding just one thought to his telling of this well-known kōan: “This is an excellent example of the way of Buddhas.”

There are double-mirrors in this Buddha mind – Dōgen shares a kōan about a teacher-student transmission of the Buddha mind, by quoting his teacher minding the kōan and affirming it as a telling example.

In any case, Dàméi heard “Mind itself is Buddha,” had great realization (6), and then went to the mountains to do zazen night and day for thirty years. Dōgen and Rujing too, according to Dōgen, raise this as an example of how to proceed with practice after enlightenment. Dàméi eventually did lead both Juzhi, famous for holding up his finger, and Jianzhi, who transmitted Zen to Korea, to enlightenment. But it is his thirty-years zazen in the mountains that Dōgen and Rujing call out for praise.

More on this point below.

Dōgen’s comment

It may be deduced that sitting meditation is post-enlightenment practice. Enlightenment is just sitting meditation, that’s all. This mountain is the first to have a communal hall; this is the first it has been heard of in Japan. The first one has been seen, the first one has been entered, the first one has been sat in. This is lucky for people who study the path of Buddha.

I was originally drawn to reflect on this dharma discourse of Dōgen’s because of this reference to “post-enlightenment practice,” something that I associate more strongly with Hakuin Zen than Dōgen Zen. After rolling the whole discourse around, though, I find it extraordinarily rich and representative of several important themes for Dōgen and for us.

Even Dōgen’s first sentences cover a lot of ground, the last three of which might seem at first to be unrelated to the first two. Dōgen begins with the entanglement of enlightenment, “this mind is Buddha,” and zazen by asserting that zazen is a fitting practice after enlightenment. What about before enlightenment? Is zazen a practice for beginners and those who haven’t yet experienced enlightenment and then zazen continues to be the practice after enlightenment? Or is Dōgen saying here that zazen, or perhaps true zazen, is only a post-enlightenment practice, that one isn’t really doing zazen prior to enlightenment.

It seems to me that Dōgen means just what he says. “…Sitting meditation is post-enlightenment practice.” For Dōgen, zazen is the Buddha mandala, the Buddha land presented here and now through our enlightened psycho-physical zazen pose, where the refining of enlightenment and the presentation of enlightenment are like the front and back of the hand.

Curiously, from an assertion about the importance of post-enlightenment zazen, Dōgen moves on to boast about establishing the first “communal hall” or “monks’ hall” (Japanese, sōdō) in Japan and notes how fortunate people are now to have such a hall. What’s the connection? Dàméi, after all, was not practicing in a monks’ hall, but in the mountains, eating pine pollen and wearing lotus leaves. But that doesn’t seem to be the point that Dōgen wants to highlight.

It is important to appreciate that the monks’ hall is the place that monks would sleep, eat, wash, use the toilet, and sit zazen. One way to make sense of the flow of the argument here is to see the monks’ hall as an extension of the zazen pose, an extension of the Buddha mandala that is enlightenment. The sentences then unfold Dōgen’s point through multiple dimensions – the person and the environment, time and space. That extension also includes the clothes worn, particularly the kesa, although that is not included by Dōgen in this discourse. The specific, prescribed form and function of monks’ hall become part and parcel of Dōgen’s zazen as enlightenment, a full-bodied dharma presentation.

In my view, Dōgen, in the first movement of this discourse, uses a traditional kōan involving well-known Zen heros, Dàméi and Mǎzǔ, and the vague endorsement of his teacher, Rujing, to support his notion of the importance of zazen and then extends the argument to include the spatial construction of the Buddha realm. One might ask, “Is zazen enlightenment if not undertaken in a proper monks’ hall?”

Without hesitation, most of us would answer that question, “Yes.” How Dōgen would respond cannot be known, but I suspect he might say, “No.”

We know, for example, that Dōgen started giving formal dharma hall discourses only when he had a proper dharma hall, stopped giving them during his move to Eiheiji when such a dharma hall was unavailable, and then started again when the proper hall was completed.

Dōgen, despite how he is often presented today as teaching that our life as-it-is is the fundamental issue at hand (genjokoan), he may well have had quite a different perspective, something akin to a synthesis of Zen and esoteric Buddhism, requiring specific physical structures both in the body and buildings (7).

Subsequent kōan development

A monk subsequently said to “What principle did you realize when you met master Mǎzǔ, that you dwell on this mountain?”

Dàméi said, “Mǎzǔ told me, ‘Mind is Buddha.’”

The monk said, “Mǎzǔ’s Buddhism is different these days.”

Dàméi said, “How is it different?”

The monk said, “These days he says, ‘Not mind, not Buddha.’”

Dàméi said, “This old fellow confuses people no end. Let it be, for him, ‘not mind, not Buddha,’ for me, simply, ‘mind is Buddha.’”

The monk went back and recounted this to Mǎzǔ. Mǎzǔ said, “The plum is ripe.”

Dōgen’s subsequent kōan comment

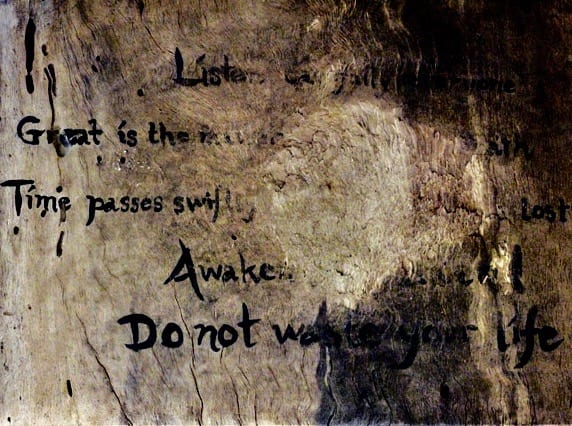

So someone who has understood mind itself is Buddha gives up human society, goes deep into mountain valleys, and just sits meditating day and night. The brethren on this mountain should simply focus solely on sitting meditation. Don’t waste time; human life is impermanent. What are you waiting for? I pray, I pray.

Do you want to understand the principle of ‘mind itself is Buddha’? (silence)

‘Mind itself is Buddha’ is very hard to understand. ‘Mind’ is walls, tiles, and pebbles. ‘Buddha’ is a mud ball, an earth clod. Mǎzǔ speaking up was dragging mud and dripping water; Dàméi waking up was haunting the weeds and woods. Where is the identity of mind and Buddha? Huh!

Let’s first look at the second portion of this last section, the clincher – “‘Mind itself is Buddha’ is very hard to understand … Where is the identity of mind and Buddha? Huh!”

Here old Dōgen pushes his audience to awaken, not to hide behind the fame of Dàméi and Mǎzǔ, as they too are splattered with mud and soaking wet. Dōgen’s admonition is for us to discover our essential identity, Buddha as mud and earth, song of the bird, hum of the car. The so-called true self.

So in terms of urging personal enlightenment, Dōgen wraps up this discourse like any Zen master would. Such an admonition, of course, only makes sense if for Dōgen enlightenment is personal experience. In other words, that enlightenment isn’t the zazen of all people, all the time. True zazen, post-enlightenment zazen, is what Dōgen sees in Dàméi and what he prescribes for us in the post-enlightenment period of practice. Especially when that zazen occurs in a proper monks’ hall.

How I got Dōgen wrong

Let’s now look at the first paragraph of Dōgen’s comments on this last section. He begins by affirming that “…someone who has understood mind itself is Buddha gives up human society, goes deep into mountain valleys, and just sits meditating day and night.”

In contemporary Zen, we talk about going up the mountain, undertaking some years of formal Zen training, and then coming down the mountain, entering the world to benefit living beings. In this passage, at least, Dōgen leaves us up the mountain just sitting. What about the vow to carry all living beings across the flood of suffering?

Dōgen does, of course, express his great vehicle bodhisattva heart elsewhere. For example, he wrote two Shobogenzo fascicles on arousing the way-seeking mind. And in his poetry, there’s this:

Awake or asleep

in a grass hut,

what I pray for is

to bring others across

before myself.

And yet, the spirit of “coming down the mountain” isn’t explicit in this passage, or it could be argued, in Dōgen’s later teaching generally. It isn’t built into his system of practice. Sit and sit some more, seems to be the message. And in that post-enlightenment just sitting, the kōan is realized, it is discovered that all living beings are already free.

However, it would be kinda nice for as many people as possible to know this for themselves. If you stay cloistered in the mountain in your proper monks’ hall, is that the most skillful means to actualize the bodhisattva heart?

Let’s look at Hakuin for another example. Here Norman Waddell writes about Hakuin’s final, definitive enlightenment experience that occurred while reading the “Skillful Means” chapter of the Lotus Sutra:

“In that chapter, the Buddha reveals to his disciple Shariputra the true nature of the Mahayana Bodhisattva, whose own enlightenment is but the first step in his career of assisting others to attain theirs. This is identical to the teaching Shōju had tried to drive home to Hakuin years before. Like Shariputra, Hakuin had erroneously regarded his original realization as full and perfect enlightenment, and he would have been unable to proceed beyond that realization without the timely assistance of a genuine teacher.

“As Hakuin read, the sound of a cricket churring at the foundation stones of the temple reached his ears; at that instant, he crossed the threshold into great enlightenment. The accumulated doubts and uncertainties of forty years suddenly ceased to exist. The reason why the Lotus Sutra was regarded as supreme among all the Buddha’s preachings was revealed to him “with blinding clarity.” He found teardrops “cascading down his face like strings of beads—they poured out like beans from a ruptured sack (8).”

From that point on, Hakuin worked tirelessly, his post-enlightenment practice, to help people realize enlightenment. The heart of the bodhisattva life for Hakuin, as catalyzed through his work with Shōju and finally discovered definitively when hearing a cricket and reading about the reason Buddhas come into the world, was to help beings awaken. That involved sitting zazen, of course, but also breaking through the kōans and clarifying enlightenment after enlightenment. And it beared fruit. By the end of Hakuin’s life he had some eighty enlightened successors.

Quite a contrast to Dōgen’s leaving human society and “…just sit meditating day and night.”

And that’s how I’ve gotten Dōgen wrong. I’ve argued, you see, that Dōgen’s career can be seen as an effort to rehabilitate the Sōtō lineage after it took an unfortunate detour into the quietism of silent lllumination. For Dōgen, zazen is the vivid cultivation of verification, the kōan realized (9). Yet, when it comes to Dōgen’s presentation in this discourse regarding practice after enlightenment, there are clear traces of quietism in Dōgen’s Zen.

Hakuin, on the other hand, offers a passionate alternative. The vow to free all living beings is taken up and actualized concretely in doing whatever can be done to cultivate verification, practice enlightenment. Post enlightenment practice becomes tireless service to catalyze the enlightenment of others.

There is, of course, no one right way. I hope that this culling out of a couple of the possibilities might serve you before, after, and during enlightenment.

____________

(1) See Daido Loori’s, The True Dharma Eye: Zen Master Dōgen’s Three Hundred Kōans, 278.

(2) This dharma discourse is in Cleary’s Eihei Koroku as Volume 4, number 61. In the Leighton and Okumura translation, Dōgen’s Extensive Record, it is number 319.

(3) Cleary has the Japanese for names throughout, but I’ve changed them to the more standard Chinese. Except for the Japanese monk, Dōgen.

(4) Dàméi Fachang 大梅法常 (752-839). Dàméi means “great plum.” Cleary has “big apricot.”

(4) Mǎzǔ Daoyi 馬祖道一 (709–788). Mǎzǔ means “horse ancestor.”

(5) Although not included in this version, in Dōgen’s telling of the story in “Continuous Practice,” he has this: “Upon hearing these words, [Dàméi] had realization.”

(6) Mandala: “… The practitioner imagines the entire universe as purified and transformed into the transcendent maṇḍala— often identifying himself or herself with the form of the main deity at the center.” The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism.

(7) See Icons and Iconoclasm in Japanese Buddhism: Kukai and Dogen on the Art of Enlightenment, by Pamela D. Winfield for more on this.

(8) Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin

(9) See, for example, Dōgen’s reworking of Hongzhi’s “needle point of zazen” poem in the third section of “Zazenshin.”

____________

Zenshin Tim Buckley, a Zen priest affiliated with the San Francisco Zen Center system and the teacher at Great River Zendo near West Bath, Maine, died yesterday.

Zenshin Tim Buckley, a Zen priest affiliated with the San Francisco Zen Center system and the teacher at Great River Zendo near West Bath, Maine, died yesterday.

Arising-extinguishing is the activity of this life-death. The kōan that I’ll be presenting today asks this question: “Who is arising-extinguishing?”

Arising-extinguishing is the activity of this life-death. The kōan that I’ll be presenting today asks this question: “Who is arising-extinguishing?”