Where Art Thou “God”?

“God” is not a word we hear a lot of in Paganism. We hear about:

gods (plural),

Goddess (feminine),

the god (accompanied by the definite article and often lower case “g”), who is the consort of the Goddess,

and a god (accompanied by the indefinite article and referring to one of many),

but nothing really about “God” (capitalized and singular).

The reason is that much of Neo-Pagan and Polytheists theology represents an intentional challenge to or critique of the traditional Western conception of divinity. But is it time for Pagans to reclaim God?

God vs. the Goddess

For many people who have been raised in Western civilization, whether or not they belong to an Abrahamic faith, the word “God” invokes images and qualities associated with the monotheistic god of the Abrahamic faiths, including transcendence, hierarchy, masculinity, dominance, power-over, etc. The Neo-Pagan Goddess, in contrast, is associated with embodiment, relationality, cyclicity, the chthonic, and the antinomian. The many gods of contemporary Paganism add the qualities of plurality and diversity to the Pagan conception of the divine. As such, both the Neo-Pagan Goddess and the many gods of contemporary Paganism are a needed corrective to an imbalanced image of the divine offered by the Abrahamic faiths.

But in spite of their having left the Abrahamic God behind, the word “God” remains an emotionally and psychologically charged word for many Pagans. Far from being devoid of content, the word is filled with meaning — usually a negative meaning — derived from the Abrahamic faiths. For a long time after I left my faith of origin (Mormonism), the word “God” itself had such strong negative emotional associations that I avoided its use, unless it was prefaced by a definite or indefinite article (“the” or “a”). Even in Pagan contexts, I preferred to use words like the “divine” or “deity”.

It was precisely the negative connotations of the word “God” that made just saying the word “Goddess” such a powerful and healing experience for me. It opened up realms of theological possibility previously unexplored by me, possibilities that I later came to realize in experience. “Goddess” represented for me the possibility of a deity that cared nothing about traditional notions of purity and obedience, a deity that could be experienced immanently, in the material world around me and in my own body.

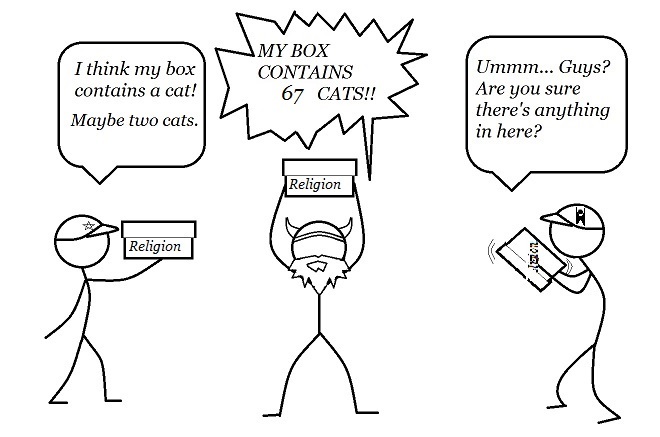

Refilling My “God Box”

But after many years of avoiding “God”, I gradually began to experience the word being emptied of its negative associations. Eventually, I regained the ability to talk about “God” again — not the God of my Christian upbringing and not a masculine counterpart to the Goddess either. “God” became for me, rather, a linguistic container or “box”. For the most part, I kept this box empty, intentionally, a container for my longing for that which cannot be articulated.

But sometimes, I put different things in my “God box”, trying on different conceptions of the divine, but only for a while. I kept in mind Ann Ulanov’s observation about both the potential and the limitations of theistic imagery: “It is very much a human impulse to try to picture God and God does come to find us in those very pictures as well as in the smashing of them.”

You might wonder why I would want to keep my “God box” at all. As B. T. Newberg has explained, the word “God” retains power, even when it is emptied of its content. As proof of this, consider how many anti-theistic atheists still experience the word as emotionally provocative. Newberg writes:

“The word “god” is embedded in a complex web of associations. Considering its proven ability to inspire powerful emotions and myriad creative interpretations over the centuries, we might say that it is particularly rich in this regard. It is critical to note that among its associations are a sense of heightened importance (sacredness), ultimate questions (e.g., why are we here), and a relation to moral values (how we live our lives). These grant it a unique power to evoke experiences of profound importance and moral relevance.” — B. T. Newberg, “In Defense of Gods” in Godless Paganism (2016).

Reclaiming God

I wonder whether Pagans should reclaim the word “God” from the Abrahamic faiths. Reclaiming is, in my opinion, a quintessentially (Neo-)Pagan activity. We’ve reclaimed ancient gods (like Ba’al), goddesses (like Asherah), and demons (like Lilith). We’ve reclaimed witchcraft and magic. Some of us have even reclaimed Satan. So why not reclaim “God”?

I belong to two religious communities, both of which are ambivalent, if not downright antagonistic, about the word “God”. The first is religious naturalism, which includes Unitarian Universalists and Humansitic Paganism. B. T. Newberg explains why it is important that religious naturalists not surrender the word “God” to the monotheistic literalists.

“It has been shown to have powerful advantages, and relinquishing the term to literalists hands over exclusive control of a potentially destructive weapon. Instead, naturalists can continue the age-old tradition of contested meanings by affirming naturalistic definitions alongside supernatural ones. Naturalist usage of the word “god” subverts literalist dominance, reclaims the word, and evolves it in directions compatible with modern scientific discovery.” — B. T. Newberg, “In Defense of Gods” in Godless Paganism (2016).

The other community I belong to is Paganism. Even those Pagans who are no longer triggered by the word “God” may not see the point of reclaiming it. After all, we’ve got gods (plural) and the Goddess (a feminine monistic deity), what do we need with God?

All these words we use to describe the divine (even “the divine”) are linguistic tools. Each of them says something different about divinity. Speaking of the gods in their plurality reminds us of the multiplicity of the divine, the uniqueness of each of its parts. Speaking of the Goddess in the singular reminds us of the unifying ground of Being which transcends multiplicity without denying its reality, the unity which connects the diverse parts of nature. And She and reminds us to look for the divine in the flesh, in our relationships, in the cycles of nature, in the earthy, and in the chaotic. Both of these — the gods and the Goddess — are personifications which enable us to relate to the divine in a way that we cannot to impersonal metaphors like “the divine”. But we need not see these expressions of divinity — singular and plural, personal and impersonal — as mutually exclusive. We can take a page from the ancient Greeks who, going all the way back to Homer, spoke interchangeably about the gods (theoi) and God (theos).

But there are still more possibilities than the many gods and the one Goddess. The tricky thing about language is that it both opens up horizons of possibility, while it also delimiting or foreclosing other possibilities. When we choose a word to describe something, we are simultaneously choosing not to use other words. Saying “Goddess” allows us to say certain things about divinity, but it doesn’t allow us to say all things. And there is always more to be said. “Goddess” is first and foremost a gendered way of speaking about divinity. “God”, while historically gendered male, is not universally understood in that way, not be Christians or other monotheists. Consider that many Pagans speak of the “gods” inclusively as referring to both male gods and female goddesses.

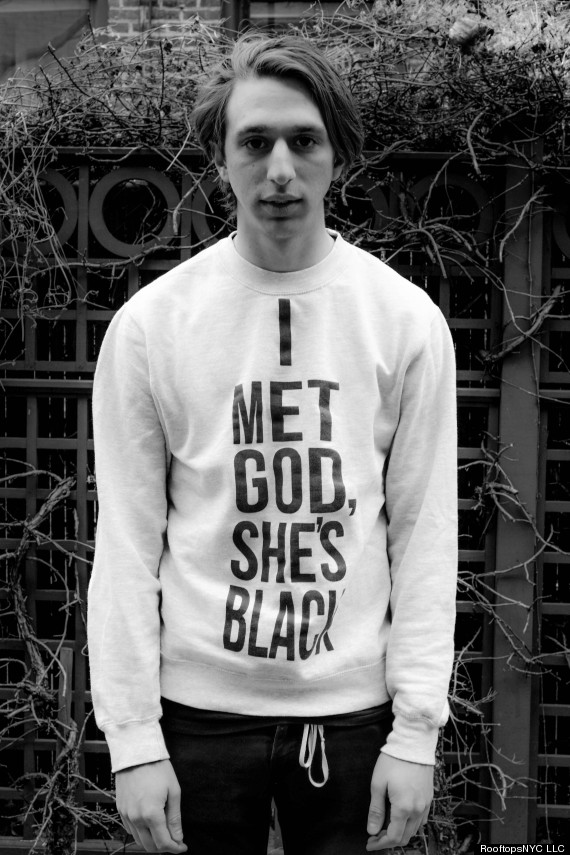

Choosing to say “God” instead of “Goddess” allows us to speak about divinity separately from gender, while also allowing us to tap into all the power and possibility that has been associated with that word for centuries. It also allows us to challenge the Abrahamic conceptions of God more directly. In some ways, memes like “I met God. She’s Black.” or “God is coming. And She is pissed.” are even more provocative than saying “Goddess”. Talk about “Goddess” can be ignored by Abrahamics as something distinct from “God” (“They’re not talking about our God.”), while talk about “God” (i.e., as She or as Black) is not so easy to ignore. This is another reason why we Pagans need to reclaim “God”.

I’m not suggesting a return to transcendental monotheism or a return of the Abrahamic patriarch. And I’m not suggesting we choose God over the gods or the Goddess. I’m suggesting we embrace all of these words … and more: “gods”, “goddesses”, “Goddess”, and even “God”, each of them with their unique potential and their unique limitations. We Pagans know something about the infinite diversity of the divine, and we need all of the linguistic resources at our disposal to express it. So let’s reclaim “God” from the monotheists and the patriarchs. Let’s make “God” Pagan again!