There are still some people around who like to claim that they are an initiated priestess of an unbroken lineage from ancient Wales which looks strangely like modern Wicca, or some similar nonsense. As a kind of backlash, most people who want to be taken seriously would tell you that there are no unbroken religious traditions that survive from ancient times. That isn’t actually true either. They are just looking in the wrong place.

First you have to understand that in my opinion, magic is religion. You are appealing to unseen forces and beings to achieve a desired result: a deity, a fairy, a saint, the spirit of a given plant or stone or location, the dead. The seeker may or may not appeal to a specialist in such matters, may or may not understand the cosmology underpinning the spell, and his or her relationship with the being appealed to may be purely transactional rather than reverent…none of which especially differentiates magic from religion. The main difference is objective: the goals of magic (and, I would argue, much of religion as actually practiced by individual people) are usually immediate, practical, and personal; those of religion as a group enterprise more long-term, abstract, and social. Which gives a clue as to why the former is so very long-lasting: Empires rise and fall, but people’s personal concerns are both universal and eternal. If you don’t believe me, read some Roman graffiti some time. Or this Babylonian letter of complaint.

Secondly, you have to understand that syncretism does not bother me. Cultural drift is a fundamental trait of human society. Moreover, there is no pure, original state of any culture. Every society we have record of is the result of trade, migration, conquest, intermarriage, upheavals, and the kind of good fortune that brings people flocking to your community…all of which are prone to cause people to encounter new things and incorporate them into whatever they were already doing.

In any case, people have probably used spoken charms since we invented language and religion, both of which may be older than our actual species. They have definitely been using written charms since they invented written language…there are Sumerian, Babylonian, and Egyptian examples of written incantations which were meant to be placed somewhere in the house or carried as amulets. Not only is the practice ancient; it continued right through the Roman Empire, the medieval period, and on into the modern era. I have a photocopy of one such talisman dating from the 18th century, written in Gaelic and sewn inside clothing, from the North Carolina State Archives. In Powwowing in Union County, Barbara Reimensnyder describes the himmelsbrief, a written prayer for protection which 20th century Americans would hang on the wall or carry with them in times of danger…just like an ancient Babylonian. The specific details…like which deity is being called upon…tend to change, but the forms over the millennia have remained remarkably the same.

But what if I told you that there’s an ancient Roman spell that is still around, and has been in continuous use for the last 2000 years?

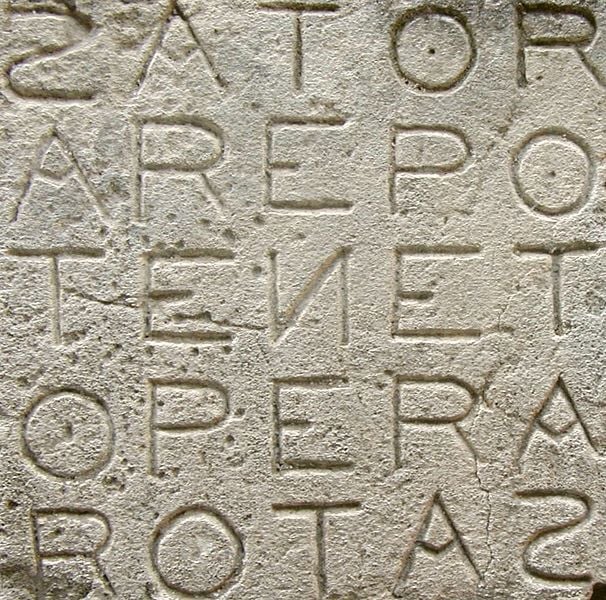

That would be the Sator square. Most written formulas depend on identification or appeal to a divine figure; the magical power of this one draws also on the fact that it is a palindrome that forms a magic square; that is, it reads the same backward, forward, down, or up, and on the magical qualities of writing itself. Like this:

S A T O R

A R E P O

T E N E T

O P E R A

R O T A S

A version of the Sator square was found in Pompeii; other examples are carved into medieval churches, and it also appears in popular grimoires from the Renaissance era onward. Some variants start with “ROTAS” on top, which does not affect the meaning because, like Greek, Latin grammar goes by declensions rather than position. It is typically written and hung on, or sometimes carved into, a wall. The Long Lost Friend recommends writing it on a plate. The sentence is dubiously grammatical Latin and means something like “the sower Arepo holds (believes in) the working of the wheel.” It is used for protection in general and specifically against theft or fire; that, and the fact that all of the extant examples of its use in antiquity are on buildings, implies that it was originally meant for protecting the home. However, as I’ve mentioned, making a portable version and carrying such a talisman with you is well within the bounds of tradition.

It’s worth noting that nobody is sure what “AREPO” means. The form suggests a name, but that doesn’t help much either; Arepo as a figure appears nowhere else in Roman times, and attempts to explain it as code for Christ appear to be ret-conning. I think that, given the Roman penchant for having gods of absolutely everything, that it’s possible they just decided that a name that completed a square like that must be a god. It’s also quite possible that it is a Latinization of a word from another language which we don’t know because it was never written down, or that the other uses of it are simply lost. Perhaps some day an archeologist will find a carving or fragment of a scroll that explains what Arepo means; until then we just have to wonder. The mysterious quality of this simple little bit of protection magic, which has survived for two millennia at least, is part of its charm.

Find me on Facebook! A Word to the Witch