This is so blisteringly obvious that it’s hardly worth mentioning, but there is a difference between the high-school proms of our grandparents and the proms of current high-school kids. A brief survey of 1950’s-1960’s prom footage shows, somewhat shockingly, that there was dancing. That is, there were dances and people knew them. Men held the hips of women cupping the shoulders of their man, shuffling through sets of understood and pre-ordained movements of the foot and sways of the waist, achieving to greater or lesser degrees some semblance of bodily grace.

This is so blisteringly obvious that it’s hardly worth mentioning, but there is a difference between the high-school proms of our grandparents and the proms of current high-school kids. A brief survey of 1950’s-1960’s prom footage shows, somewhat shockingly, that there was dancing. That is, there were dances and people knew them. Men held the hips of women cupping the shoulders of their man, shuffling through sets of understood and pre-ordained movements of the foot and sways of the waist, achieving to greater or lesser degrees some semblance of bodily grace.

Now I’ve had the ambivalent pleasure of attending a few proms, and have come to the evidence-based conclusion that the majority of high-schoolers attending a school dance are in one of four positions. They either (a) circle the dance floor, grinning nervously, touring and observing the teeming mass, finding it utterly impossible to join, the very idea of continuous, synchronized bodily motion ringing in their ears as an absurdity or (b) if they do join, they form a circle of similarly awkward friends and dance ironically, usually doing “the robot” in the vague hope that joking-about-dancing in a group of six or seven will add up to actually dancing or (c) they arrive so very baked that the issue of intentional bodily movement has already been annihilated or (d) if they are among those who will dance with the opposite sex, they perform that sublime, graceful, intimate motion known as grinding, in which the male erection is rubbed through tuxedo pants by a female rear-end.

Now it is a Christian tendency to regard the difference and call it an overwhelming rise of vice and the result of the sexual revolution, but — and forgive me if this is a foolish mistake — I was under the impression that sexual liberation, moral or immoral, would be a good-deal, well, sexier. Sinful — perhaps — but fiery, passionate, and erotic, not the gyration of female rear to male front for the duration of a thumping, unchanging piece of pop music. Something with flavor. Dances between men and women are by their very nature sexual, and frankly, you’d be hard-pressed to find a human tradition that better contains and expresses the erotic than tango.

But our youth culture is not getting better at tango, nor dancing, nor the contact of male and female in any structure of intimacy and sway. We’re not even developing danceable music. It’s a bitter sort of irony, but we are becoming disembodied. Ghostly.

These are the days of miracles and wonders in which the body is largely viewed as a thing extraneous to ourself, a cage for who-we-are, as if life began with condemnation to animate and lug around a corpse. We have embraced a duplicitous view of the human person, one that says, to summarize, “I am not body.” I haven’t a damn clue where this comes from — perhaps Descartes, perhaps Satan — but the fact of it’s existence seems apparent, and not just in the high school prom.

Eating Disorders

The eating disorder is a perfect example of a disintegration between the body and the soul, in that the person who suffers it believes themselves to be fat even though their body is — by all standards — frightfully skinny. I’m not arguing that eating disorders are caused by a direct confrontation with bad philosophy. They are often triggered by abuse, and recent research has pointed to a potential genetic capacity for the development of eating disorders.

The eating disorder is a perfect example of a disintegration between the body and the soul, in that the person who suffers it believes themselves to be fat even though their body is — by all standards — frightfully skinny. I’m not arguing that eating disorders are caused by a direct confrontation with bad philosophy. They are often triggered by abuse, and recent research has pointed to a potential genetic capacity for the development of eating disorders.

But the prevalent idea that “I am not my body,” is precisely the frame of mind for so many of those suffering from anorexia, bullemia, and all the rest, and I have no doubt that our idiocy shoulders some of the responsibility for the “near threefold increase [in anorexia] over the past 40 years among women in their 20s and 30s, 6.28 (1950-1964) versus 17.70 (1980-1992) cases per 100,000 per year.” (1) The anti-body philosophy is, after all, a western one. It’s the white kids who aren’t dancing. This philosophy — which is the modus operandi of a media that portrays a woman’s beauty as dependent on her working against her natural body — explains why these “syndromes are more prevalent in industrialized and often Western cultures” and why bulimia is considered a “culture bound syndrome,” and why “were unable to find evidence of the disorder arising in the absence of Western influence.” (2)

Nudity

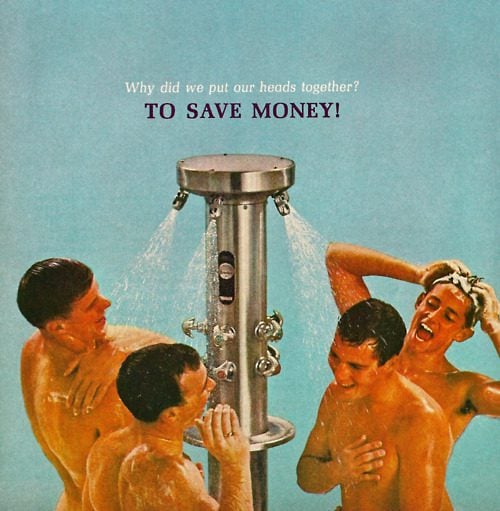

Or consider an issue I’ve written about before. This picture…

…can only be taken as a joke, but just 60 years ago it was an advertisement. Our modern chuckle indicates our shift towards a male discomfort with male nudity, a discomfort mirrored in the redesigning of locker rooms and showers to include private changing rooms, partitions, and dividers. On the surface — what with our culture’s uncanny ability to exploit every curve of the human body to sell food and cars — it might seem that we’re far more comfortable with our bodies than our grandfathers. But the surface sucks, and reality always calls for a deeper dive.

Sexuality

I don’t know if we adore the disintegration of body and soul because it contributes to our view of sexuality, or whether our liaison with disintegration is precisely what causes our view of sexuality, what with its deliciously ghostly quality of having very little to do with the body at all. “I am not my body,” we again affirm in our happy embrace of transsexualism, pansexualism and all the exponentially multiplying number of objective classifications for our varied “sexualities.” I’m sexually attracted to your soul, says the “pansexual,” to your intelligence, says the “sapiosexual” — the body has nothing to do with it. In the case of transgenderism and transsexualism, we applaud the man “trapped in a female body” as an expression of authentic sexuality. After all, “you are not your body,” and who knows how many woman-souls are floating in the wrong corpse! Modern gender theory renders the human person an accident, a gamble of gender and sex rolled by who-knows in pre-existence. It’s merely good luck if your body and soul have anything to do with each other.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qFKmzR5AejgSo let’s be honest with ourselves. The disintegration of body and soul is everywhere. It’s in the movement away from religions grounded in physical, sacramental experience and towards evanescent, abstract “spiritualities” that have us transcending our sweaty, earthy existence. It’s in the massive rise in aesthetic plastic surgeries that artificially modify the body as if it were merely an accidental object we happen to inhabit. It’s in pornography, which uses the body — without the soul — for sexual pleasure — without sex. And yes, it rips at the high-schoolers attending what can only be called in jest “a dance.”

But I hear an indignant voice calling from somewhere in the middle of a Flo Rida beat: But look at the mad sex you can have! Call it what you may, but the movement from dancing to grinding is surely — if nothing else — a sexual movement, and most certainly a use of the body. This, I suppose, is what I really want to get at, not with any wisdom of my own, but with that of the southern novelist Walker Percy, who says:

“The Self since the time of Descartes has been stranded, split off from everything else in the Cosmos, a mind which professes to understand bodies and galaxies but is by the very act of understanding marooned in the Cosmos, with which it has no connection. It therefore needs to exercise every option in order to reassure itself that it is not a ghost but is rather a self among other selves. One such option is a sexual encounter. Another is war. The pleasure of a sexual encounter derives not only from physical gratification but also from the demonstration to oneself that, despite one’s own ghostliness, one is, for the moment at least, a sexual being. Amazing! Indeed, the most amazing of all the creatures in the Cosmos: a ghost with an erection! Yet not really amazing, for only if the abstracted ghost has an erection can it, like Jove spying Europa on the beach, enter the human condition.”

The incidence of sexual arousal arrives like a blessing from above, for by it the body is rendered simple. We are no longer ghosts inhabiting an accidentally assigned corpse, ghosts for whom the body is a thing-to-be-fought, rather, we feel in our bodies an urge that makes sense, a semblance of integration in which we want what our bodies want. The sexually aroused body now has a purpose and a function to be worked with, not against — the function of getting laid.

That grinding has replaced dancing as the primary bodily interaction to popular music is not evidence for a warm embrace of the body. It is evidence for the fact that we can only embrace the body when it is reduced to stimulated thing that needs stimulus-response. The body-soul conundrum is overcome by the animalization of the human person, by the elimination of the soul as the governing principle of the body and the elevation of the bodily urge to its place. We must follow our urges. By reducing our bodily behavior to that of a dog humping a couch, we finally feel embodied, and as long as it lasts, grinding is our incarnation, for we desire nothing more than what our body desires, and the divided human is at long last made one.

Of course the result of limiting embodiment to the incidence of sexual arousal means that we can only see the body as a sexual object. Thus the dearth of the group shower, for in the removal of the towel, we are purely eroticized beings, and frankly, no one at the gym wants to shower with purely eroticized beings, much less reveal himself as such. Grinding must replace dancing, for the body pressed against the body in something other than an act of stimulus-response is awkward. It can be said, in all honesty, that we need arousal like we need salvation.

Now into this sadness — and it is a sadness, if only because we can never maintain this method of embodiment for longer than an erection — sound philosophy speaks an alternative, or rather, the truth from which all “alternatives” fall. The soul expresses the body. The body is a physical expression of the soul. The soul without the body is a ghost, the body without the soul is a corpse, and both are considered by all humanity with horror and disgust for a reason. Any disintegration of the two is a withering of the human person — integration is his blossoming. Everything we know comes first through the body. We are conceived, and the universe hurls itself — not against our soul and our intellect — but against our nerve-endings and tiny, reaching fingers. We taste, touch, see, smell and hear, gathering information by our two-legged foothold in the physical universe, and only by this physical functioning do we develop as spiritual beings — beings with language, ideas, and self-awareness. (Consider Helen Keller.) On the other hand, only because we have a soul do our sense-perceptions transcend the world of stimulus response, making us qualitatively different from the ape, who has sense-perception but neither language nor art nor humanity. The intellect — which is spiritual — operates in harmony with the senses — which are physical. Without a working integration of body and soul there is no humanity, no language, no art, and ultimately no knowledge in the universe.

Now into this sadness — and it is a sadness, if only because we can never maintain this method of embodiment for longer than an erection — sound philosophy speaks an alternative, or rather, the truth from which all “alternatives” fall. The soul expresses the body. The body is a physical expression of the soul. The soul without the body is a ghost, the body without the soul is a corpse, and both are considered by all humanity with horror and disgust for a reason. Any disintegration of the two is a withering of the human person — integration is his blossoming. Everything we know comes first through the body. We are conceived, and the universe hurls itself — not against our soul and our intellect — but against our nerve-endings and tiny, reaching fingers. We taste, touch, see, smell and hear, gathering information by our two-legged foothold in the physical universe, and only by this physical functioning do we develop as spiritual beings — beings with language, ideas, and self-awareness. (Consider Helen Keller.) On the other hand, only because we have a soul do our sense-perceptions transcend the world of stimulus response, making us qualitatively different from the ape, who has sense-perception but neither language nor art nor humanity. The intellect — which is spiritual — operates in harmony with the senses — which are physical. Without a working integration of body and soul there is no humanity, no language, no art, and ultimately no knowledge in the universe.

But this cannot be told to a culture that orbits the depth of the body like people by a pool, afraid to swim, only braving the dive in the event of sexual arousal. (A weird image, I’ll admit.) The value of integration must be shown. First of all, by our lives, by the virtues of modesty and chastity by which we live like humans, and then by art. The experience of beauty destroys our barriers and ushers a person into an encounter with the truth. Art, music, poetry, and even architecture need to express the beauty of the integration of body and soul, not out of some desire to make a point — for political art is lame — but out of our own, authentic, artistic encounter with the human person as neither a ghost, nor a corpse, but relation.

(1) Pawluck, Gorey, “Secular trends in the incidence of anorexia nervosa: integrative review of population-based studies.” International Journal of Eating Disorders, 1998, Vol. 23, Issue 4, pp. 347-52.

(2) Keel, Klump, “Are Eating Disorders Culture-Bound Syndromes? Implications for Conceptualizing Their Etiology.” Psychological Bulletin, 2003, Vol. 129, Issue 5, pp. 747-769.