The doubts that plague me are real, and they have power. They have the power to keep me from believing in myself. Especially at critical junctures, when they always start warning, scoffing, belittling, worrying away at my hope, if I can’t muster the presence of my angels, opportunities pass me by. In time, these lost moments become regrets. They are unforgettable. Sometimes they lend me confidence in another struggle, and sometimes they add to my doubts. And so it was with the disciples –

The doubts that plague me are real, and they have power. They have the power to keep me from believing in myself. Especially at critical junctures, when they always start warning, scoffing, belittling, worrying away at my hope, if I can’t muster the presence of my angels, opportunities pass me by. In time, these lost moments become regrets. They are unforgettable. Sometimes they lend me confidence in another struggle, and sometimes they add to my doubts. And so it was with the disciples –

The Sunday after Easter is devoted to doubt. The story of Doubting Thomas is always read, no matter what year of the three year cycle we are in. Doubt is huge. And since the very first Easter, everyone has known doubt is important.

But waiting a week to bring doubt into focus makes it seem as if there is a Doubt Delay – first, you get excited and run around and celebrate – then, you doubt.

That isn’t the real story about doubt. Doubt was part of the entire Easter picture, from Maundy Thursday right through Easter Day. At the Last Supper the disciples drew back from Jesus’ foot washing – doubting his gesture, divining his meaning and shrinking from the changes to their own intentions, still intent on glory.

Outside his trial, Peter shrank into famed betrayals, unable to leave, unable to step forward, doubt and love struggling within him.

All the disciples were paralyzed by grief, the intense doubt that overwhelmed Jesus’ oft spoken assurances that he would rise, until it was Joseph of Arimathea who was able to handle the details of burial.

Pain is a guise of doubt, the mind and body unable to muster enough light to dispel the darkness. There is no record of what was said between the disciples from Friday until Easter morning, but we know what it would be among us: long silences punctuated by if onlys, why didn’t wes, how could theys. We know from their Easter astonishment that no one was saying, Let’s wait and see what happens.

Yet on Easter morning, doubt was as much their angel as their demon: some, certain of death, set out for the tomb to prepare the body. Each gospel lists different women. Always, Mary Magdelene, often his mother, and then various names. John lists Magdelene alone, who, on discovering the absence of the body runs back to tell the others, and Peter and John rush out, running ahead of her, racing each other. John arrives first but does not go in – overcome, at that point, by inner conflict, doubt surely being part of that. Peter rushes by him, enters in, sees the folded grave clothes, and his doubts and grief fall away. He rushes out, rejoicing. But Mary needs more than absence, more than clothing, more even than sight. When she hears her name, she knows.

Thomas wasn’t there in the Upper Room when they returned, wasn’t there when Jesus came and amazed them all by eating a fish. And all their telling, all their amazement, did not dispel his skepticism. Yet there was enough faith in him to keep him from walking out, exclaiming You’re nuts! and leaving their madness behind. He proclaims he has to touch those wounds in order to believe, but he stays with them, his doubt as much an angel as a demon. Some days later he has the chance to touch those wounds, it is written.

Thomas is a Greek name, and it means twin, though his twin, if he had one, never appears, and some suggest we are, each of us, his twin. For each of us has our nagging doubts that sometimes prompt us to get up and investigate a situation that needs our attention, and that sometimes hold us back. If Thomas’ doubts are the most persistent, then he is our twin because our doubts persist, and at times are insistent, and they have the ability to lead us to new discoveries about ourselves and in our relationship with all that is holy.

My doubts are not so much about whether Easter happened, though I do question that at times, but about whether it is important, whether it has anything to do with me. After all, it is from my own suffering that I long to rise.

As our culture becomes more and more dystopian, it becomes harder to set aside cynicism. Among my friends are those who fell away from Downton Abbey because the series was too impossibly sweet, and those who stayed watching, but scoffed at the series for finding too much good in a world they believe to be much crueler than that. And in the new Fox series, Rosewood, an African American Medical Examiner (Morris Chestnut) holds out hope and faith in life to all those doubters around him, who are invested in one or another form of disbelief in their ability to be accepted in this world, in their ability to survive pain, and in the power of forgiveness.

Easter insists on an end to our victimization, and opens an endless Day of Peace, which we must begin to proclaim. The disciples move through degrees of despair and doubt in each other’ company in a long, varied conversation, in which all the things they think and feel are transformed from Demons into Angels. Easter is new life, rising. Not about escaping with our life, but walking in the power of God’s love, even into death. And that’s what it has to do with each of us.

__________________________________________________________________

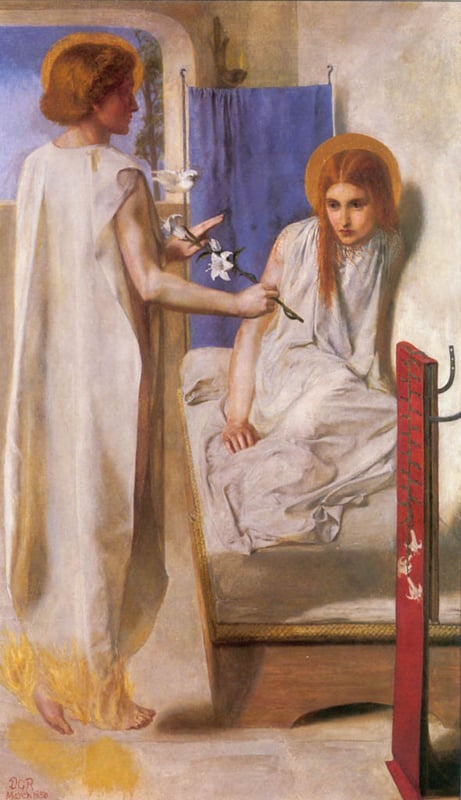

Image:

The Incredulity of St. Thomas, by Caravaggio, Michelangelo. 1601-2. Postdam,Germany. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.