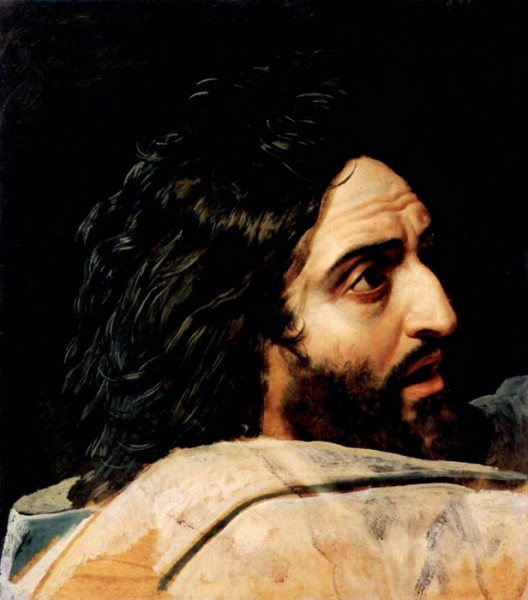

The Great Door of the Church Year swings open with the scraping noise of metal on stone. Wild Man John pushes against the door’s reluctance, leaning his shoulder into it, breathing hard as he shoves it open to reveal the darkness within.

The Great Door of the Church Year swings open with the scraping noise of metal on stone. Wild Man John pushes against the door’s reluctance, leaning his shoulder into it, breathing hard as he shoves it open to reveal the darkness within.

The Year begins in darkness, always.

Christmas, like Easter, arrives in enveloping, sheltering darkness. The light needs shelter at first, and it is only within darkness that the light can be truly seen.

The old year ends with Jesus urging his disciples to understand that it is in horror and screeching, dark and dreadful times, that God is able to be seen – not in the hushed beauty of the temple, and not in their dreams of a world beyond the ravages of time and history.

We are not, in fact, safe in this world, where death is lurking in so many forms, and nor is God safe, who comes among us because the dark is so full of terror.

And yet we somehow manage to present this Coming as an escape from just these things: death and time.

Benedict Cumberbatch, in his new film Dr. Strange, shows us the classic Marvel Comics hero battling the evil Lord of death and eternity by holding fast to time, in which he assumes a Christ-like willingness to be slain again and again, and by choosing to do this, by this fight, to hold open the life of the world, which lives in time, and not even the power of death can stop time.

Yet the church continues to blaspheme its sacred story by letting people hold to an idea of eternity as an escape that lies beyond struggle and beyond time. Not so, says Jesus, who calls his friends to plunge into struggle, to speak truth to power, to trust the Spirit to guide them through danger and to fight for the times they live in without fear of death.

The Presence of God will bring peace. But not only peace. And not without struggle.

I find myself caught in the babble of post election calls for peacemaking in which many religious voices urge a coming together that papers over the chasm that has opened among us, and belies the dark and frightening beasts that are emerging from within it.

Wild Man John exhorts people to fight within their times against their temptation to believe that they can have the riches of Caesar’s kingdoms and the endless pleasures of the empire and still be God’s people.

John inveighs, calling them a brood of vipers who choose to flee from the real work of preparing the world for God. Repent! he exhorts them, urging them to follow a different drummer – him, and the One who is to come.

We are caught in a similar dilemma: so many long for a fictive golden time when white working men were the focus of our common life, when the government offered them mortgages, business start-up loans, and college tuition if they wanted it. When they could imagine the Presence of God came only to deliver them from harm. When the Christmas Baby was always white, and blonde, and theirs.

Yet God’s earth has always belonged to all people – people who have moved across continents and seas, moved bodies and souls, languages and religions with them. Somehow the church has allowed privatization to encroach upon our minds and our land. And somehow the church has allowed hospitality for the stranger, the persistent biblical theme, to fall into dishonor among the people of God.

Our flight has been into fantasies that are ungodly at best, demonic at worst. The fight Wild Man John urges is for us to separate ourselves from all of this, in a warfare of repentance, of turning away.

This infested darkness, this bog of angers that has hold of our souls, is the place where the Presence will come. Born into no palace but in an animal’s stall, laid in an animals’ trough, then fleeing from war, the Child and his immigrant family have no papers as they arrive in Egypt, where they live as refugees outside the system, the father working any job he can find, the mother, too.

John’s repentance begins with an acknowledgement that God does not need us. We need God, who insists on joining us together as brothers and sisters, us and all the despised people in the world, this motley crew of religions and pieties.

Just getting to that relationship requires a terrific fight.

Everything else follows on from there.

Getting to Christmas, as John tells us every year, is not an easy thing.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Image: John the Baptist, by Ivanov, Aleksandr Andreevich. Moscow,Russia. Vanderbilt Divinity School Library, Art in the Christian Tradition.