After a little bit of polemic the last few days I’d like to write about something completely different: the much popularized necessity for an Islamic Reformation.

When I wrote my complete academic CV up earlier this week I realized that I’ve been either an instructor or a teaching assistant eighteen times during my academic career. Of those courses seven were taught by me as the lead instructor, and eleven as a teaching assistant. [By the way, do let me know if you have any job leads, whether academic or not.]

Being a teaching assistant is a wonderful way to pick up a lot of knowledge you’d be too lazy to pick up any other way. The great thing about it is that this knowledge usually sticks with you, because it is so unusual. In a kind of Hegelian dialectic, thanks to the strangeness of the material, you end up creatively integrating it into your own research.

Nowhere is this more true than when it comes to the last class I TA-ed for at the University of Washington: Political Science 307 World Politics and religion. The class was taught by Anthony Gill, author of Rendering unto Caesar: The Catholic Church and the State in Latin America and The Political Origins of Religious Liberty. I did a fairly well-circulated post about the fascinating reading list for that class which you should check out here.

As you’ll note from the link the class culminated with a discussion of Islamic economics and terrorism. Berman’s Radical, Religious, and Violent cuts down stereotypes of Islam as inherently violent. He instead explains how and why religious groups can be (“can” not “must”) especially efficient terrorists (long story short: for various reasons nobody organizes as comprehensively and cohesively as religious groups). On the other hand, Kuran’s Islam and Mammon undercuts what Westerners increasingly see as a positive aspect of the Muslim world they’d like to emulate: Islamic economics (long story short: the economics mostly solidify Muslim identity, but their economic and humanitarian benefits are reportedly few or not quantifiable).

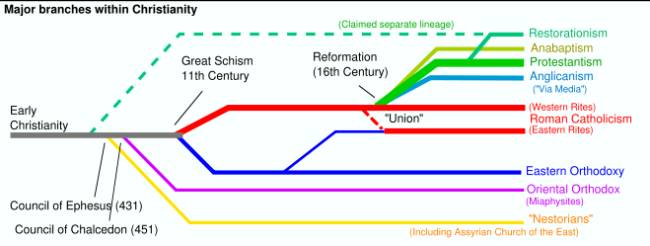

Yet, the most interesting and innovative part of the class proved to be Professor Gill’s lectures on the topic of Islamic history and its consequences. He went down the line listing all the early divisions of Islam. These events should be common knowledge to most of you with at least a cursory interest in history. There was nothing new about the story, except for the contemporary spin Gill put on them.

The way Gill sees it, or at least that’s how I understood him, Islam itself started out divided over authority. It then developed highly decentralized structures, one might say “democratic.” These structures are analogous to what happened with the Protestant denominations that came into being during the Protestant Reformation. Sounds good, doesn’t it?

The problem (for both Muslims and Protestants) is that there is no central authority, like Rome, or even something more temporary like an Inquisition, to step in an adjudicate conflicts over interpretations, or armed conflicts for that matter. The divisions over the fine points of belief are not worked out through a hierarchically structured world union. Instead, for the most part, they are worked out on the level of the mosque–frequently with each mosque trying to outdo each other in purifying their faith into the fundamentals.

Don’t forget: the concept of fundamentalism, in its more restricted Christian meaning, is something that emerged out of American Protestantism. It was only later applied to other religions

The dangerous aspects of this sort of competitive logic is something that someone like Zmirak totally misses in his Romanticized version of the Reformation, classical liberalism, and their offspring, the nation-state.

It’s not a matter of pitting totalitarian Catholicism against liberal, uhm, I suppose, liberal liberalism. Ask yourself: is it a coincidence the “Wars of Religion” started with the Reformation? The story is more complex in the West and it’s definitely even more complex outside the West.

======================================================================

UPDATE: After the still developing events in France everyone is once again talking about an Islamic Reformation. Happily, not all of it is the usual fodder. One of the most perceptive critics of the earlier version of this post suggested Islam already had a Reformation, the Wahhabist reform.

But the analogy with Christianity breaks down quickly when we consider how Wahhabism was not the dissolution of an earlier unity, but a drive to unite Islam under a fundamentalist reading of the religion.

My contention still stands: Islam still does not need a Reformation.

======================================================================

I’m not done yet with exposing truthiness:

If you’d like to learn more about the connections between Islam and world politics see my TOP10 list on the topic and all my recent posts on Islam, especially “Spreading the Blame: The West’s Exporting of Jihad.”