(After Lucas Cranach the Younger, Elector Johann Friederich of Saxony and the Reformers, 17th c; Source: Wikimedia, PD-Old-100)

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

–William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun

Reformation Day is an appropriate occasion to trot out a quote from America’s greatest (Protestant, what else?) novelist from his otherwise mediocre novel about a “nun.”

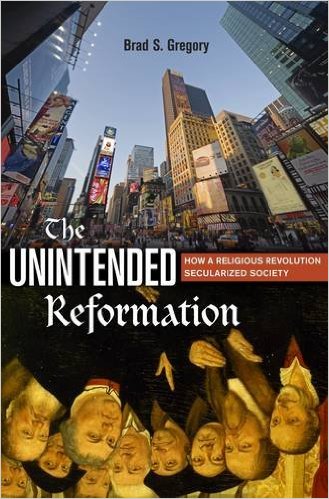

Something like this sentiment is behind one of the most discussed history and theology books of recent years, Brad Gregory’s The Unintended Reformation . Its subtitle telegraphs its rather unusually grandiose ambitions for an age that is weary of metanarratives: How a Religious Revolution Secularized Society.

The book revolves around the following continuity thesis about the Reformation:

The place of the Reformation in European history seems clear. It falls between the Middle Ages and modernity as something long gone, over and done with. It seems distant from the political realities and global capitalism of the early twenty-first century, far removed from present- day moral debates and social problems. This book argues otherwise. What transpired five centuries ago continues today profoundly to influence the lives of everyone not only in Europe and North America but all around the world, whether or not they are Christians or indeed religious believers of any kind. William Faulkner famously said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” He spoke more truly than he perhaps knew, yet in ways I doubt that he suspected.

Its conclusion about the Reformation heritage is richly pessimistic:

Its conclusion about the Reformation heritage is richly pessimistic:

[This book] analyzes the Protestant Reformation and modern philosophy as the two most important (and related) means by which attempts were made to ground truth claims by those who rejected medieval Christianity as embodied in the Roman church, which led in divergent ways to unintended pluralisms based respectively on the Bible and reason. Doctrinal impasses in the Reformation era helped to foster a renaissance of ancient epistemological skepticism and to inspire modern philosophical foundationalism. But historically and empirically, “reason alone” since Descartes has proved no more capable than “scripture alone” since Luther of providing a basis for reaching shared answers to questions about what is true, how people should live, or what they should care about. The long- term result is the open- ended multiplication of truth claims about such issues that proliferate within modern, liberal states today and that collectively contribute to Western hyperpluralism.

Criticisms of The Unintended Reformation frequently overlook how much blame Gregory puts on medieval Catholicism and its inability to found a lasting synthesis in great part because of ecclesiastical corruption.

I’ve omitted that part of the book for the sake of brevity and because it would be too charitable an observation on Reformation Day, a day when Catholics and Protestants exchange unfair barbs, thereby continuing the unintended consequences of the Reformation.

For good measure Gregory also lays contemporary American political culture, le Grand-Guignol you constantly see in your social media feeds, its hyperpluralism at the feet of the Reformers.

His description of our situation is truly bracing and worth the price of admission for its unblinking honesty:

First, along with quite a few other Americans, I am concerned about the degree to which people in the United States appear to be growing evermore politically and culturally polarized, since at least the 1980s, whether or not one thinks the phenomenon merits the designation of a “culture war.” Daniel Bell referred in 1996 to “a confused, angry, uneasy, and insecure America,” and if anything his characterization seems even more applicable now. Americans are deeply divided on many matters with major implications for their national life, including U.S. military interventions abroad, the place of religion in the public square, school vouchers and public education, abortion, race and affirmative action, gun control, the relationship between environmental protection and economic development, and the tolerability of sexually explicit and graphically violent popular culture. Whatever the issue, American national political culture as manifest in the media is lacking in rigor and loaded with rancor. Often “our own poisoned public sphere,” as Anthony Grafton has recently called it, seems little more than a shouting match of distorted and distorting slogans and propagandistic one- liners. The realities of a bumper- sticker political life seem distant from idealizations of the well- informed, fair- minded, reasonable citizens theorized by champions of deliberative democracy, whether in a Rawlsian, Habermasian, or some other form.

The scary thing, this is Halloween after all, is that our problems don’t go back a couple of decades. They go back half a millennium. Even scarier? It might be too late to fix them. The silver lining resides in the knowledge that this long enduring crisis of European life hasn’t totally destroyed everything, yet.

So, if you’re tired of the election cycle, you know who to scapegoat for it today. I, for one, am leaving the country on the 7th of November. The downside is that I’ll spend way too much time explaining the post-election chaos to foreigners. Oh well… when you can’t blame Canada, you can always blame the Reformation (and the Middle Ages).

Finally, in light of all this, my favorite Jesuit joke of all time takes on an even darker tone than usual:

What is similar about the Jesuit and Dominican Orders?

Well, they were both founded by Spaniards, St. Dominic for the Dominicans, and St. Ignatius of Loyola for the Jesuits.

They were also both founded to combat heresy: the Dominicans to fight the Albigensians, and the Jesuits to fight the Protestants.

What is different about the Jesuit and Dominican Orders?

Well, have you met any Albigensians lately?

For more Reformation Day tomfoolery see: Reformation Day Joke Polka

Consider making a donation to this blog through the donation button on the upper right side of its homepage. Times are tough.

Stay in touch! Like Cosmos the in Lost on Facebook: