It’s kinda not what it sounds like.

Today (the day I am writing) is December 29th, the Feast of St. Thomas à Becket, protector of papal interests in the complex and difficult world of medieval English church-state relations (Watt’s article in this volume teases out the tensions and ideological transformations seen by the period). From Hildebrand (see here for a zanier and more controversial take on his “life and times”) and the Investiture Controversy to the lively debates of the Avignon Papacy (see especially: Defensor pacis of Marsilius of Padua), medieval popes are often portrayed as powerful. Whether staunch reformers like Gregory VII or would-be princes like Boniface VIII, power in opposition to (and independent of) secular authority dominates our perception of the medieval papacy. The Waldensians, the Hussites, the Fraticelli, and the Lollards were supposedly reacting against a bloated Church, unrestrained by exterior powers, out for its own gain.

But what if, during at least part of the period, the Church was actually defined not by independent political assertions and defiant martyrdoms, but by subordination to, and domination by secular authority. Enter the Saeculum Obscurum, the Dark Age, the Pornocracy (meaning “prostitute rule”).

It’s really a simple story: During the 10th century multiple popes were supposedly subject to a mix of aristocratic and sexual authority, stemming from a family known as the Theophylacti. A woman named Theodora (no not the Orthodox saint!) and her daughter, Morozia, exerted undue influence on popes from Sergius III to John XII (the latter might even have been the son of the former and Morozia). Much of our information comes from the cabal’s unabashed enemy, Liutprand of Cremona, and so the stories should be taken with a grain of salt. Still, the story goes back much, much further than the Theophylacti and their Pornocracy.

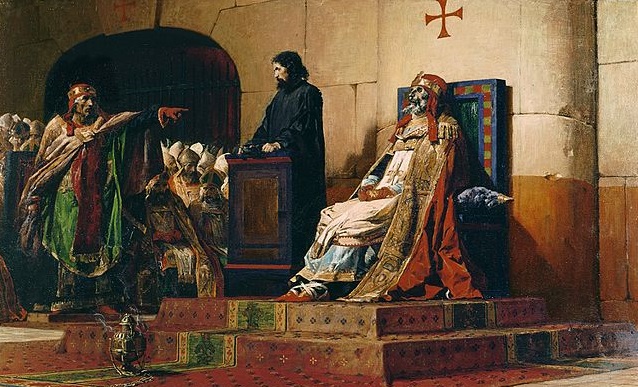

Before them, the Crescentii family dominated papal politics; before them, the German emperors enjoyed a period of dominance; before them, the Byzantines, though more remotely. Such times contain a number of impressive tales: the political turmoil experienced by Pseudo-Saint Stephen III, the Muslim and German attacks on Rome under Sergius II, and the so-called “Cadaver Synod,” during which Pope Formosus’ corpse was put on trial.

After the period in question, we also have the Tusculan Papacy, notorious for the possibly well-intentioned simony of Gregory VI and the moral laxity of Benedict IX (who was elected in his late teens or early twenties and held the throne on three separate occasions). It was only out of this mire of political backbiting and secular dominance that the occasional, reform-minded pope (and eventually the Gregorian reformers) would emerge. Papal power was predicated, in part, upon a resistance to continuing and damaging secular dominance. In the course of human things, of course, papal power became too extreme; in the interim, Thomas of Canterbury was martyred.

Why air out the papacy’s dirty laundry (seriously, I found it hard to find Catholic sources discussing this stuff in depth)? Well, because these “secular” people were Catholics. Ostensibly, they upheld the teachings of the Church; perhaps they even thought that what they were doing was right in the long term. It’s impossible to say. What we can say is that there will always be those who seek to dominate the Church and its authority; there will always be those who resist that authority. Their co-movement, their push-and-pull is wholly expected. In fact, we might wish to beware, over and above others, those who say they know what is best for the Church, not the clergy, but those who would tell us, at every turn, where the clergy goes wrong.

And, even as we say, “et ego dico tibi quia tu es Petrus et super hanc petram aedificabo ecclesiam meam et portae inferi non praevalebunt adversum eam,” we say that the occasional wave of murder, sex, even Pornocracy, is to be expected. It reminds me of something John J. O’Meara once wrote, summarizing the views of John Scotus Eriugena on human self-knowledge:

“The human mind both knows itself and does not know itself. For it knows that it is, but does not know what it is. And it is this which reveals most clearly the image of God to be in man. The human mind, likewise, is more honoured in its ignorance than in its knowledge. ‘By extension, we may know that the Church will face threats, but what precisely those threats are may remain unclear, even after sincere reflection; de die autem illa et hora nemo scit neque angeli caelorum nisi Pater solus.”

Of course, positing that, within Church history, we once accepted secular authority over and above spiritual authority, might be a bit controversial. It might even demonstrate to us that our liberal conceptions of separation of Church and State are themselves open to radical redefinition. But those are concerns for another day, or, maybe even, today.

Chase Padusniak is a doctoral student at Princeton University, where he specializes in medieval literature, especially its relationship with technology and Continental Philosophy. He has written for numerous publications, including The Intercollegiate Review, Ethika Politika, CatholicVote, and Almost Orthodoxy. He also authored the guest post Was Vatican 1 Shockingly More Political Than Vatican 2?

This was a guest post.

If by clicking on this post you weren’t expecting crime, but more gender issues, then you might want to check out either How Is Sarah Silverman Right About Jesus Being Gender Fluid? or Nudus Nudum Christum Sequi: On Christ’s Genitalia