Books are not only bibliography fodder. They are also fodder for life. Sometimes books even give life as the word miraculously becomes flesh.

I can think of several times when I’ve run up against the wall and a book has saved me. Off the top of my head I can think of Czeslaw Milosz’s The Land of Ulro, Hans Urs von Balthasar’s Mysterium Paschale, Simone Weil’s Gravity and Grace, Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead, Ernest Becker’s The Denial of Death, Nietzsche’s The Gay Science, and Walker Percy’s The Second Coming. More recently, starting on Karl Barth’s The Epistle to the Romans continues to help me tread water during all kinds of storms.

Reading is not a spectator sport. Reading is a survival tactic.

If you know anything about these books, then you’re aware they’re not straightforwardly cheerful reads, instead, they are hopeful reads (in a complicated way).

I think whenever I hit tough times I tend to instinctively follow Walker Percy’s advice from Lost in the Cosmos: If you find yourself in a difficult and depressing situation you should not reach for comedies, because the distance between what they portray and your own reality will only make you hopeless. Instead, reach for Camus or Bergman, because they will give you a sense of uplifting communion in misery.

A story in Business Insider, of all places, reminded me how much I also owe to my reading of Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. That book dropped into my lap during some difficult times and boy did it put things into perspective and I’ve found that other people who’ve read it usually have a similar response to it. This has to do with the book’s genesis. It is a combination of concentration camp memoir and a psychological-existential guidebook. Or rather, it is a psychological-existential guidebook because its insights were first discovered by the author in a Nazi concentration camp–as a prisoner.

It is difficult to do the book’s content justice in a short blog post. However, kudos to the BI writer for picking out one of the most important passages from Man’s Search for Meaning:

This uniqueness and singleness which distinguishes each individual and gives a meaning to his existence has a bearing on creative work as much as it does on human love. When the impossibility of replacing a person is realized, it allows the responsibility which a man has for his existence and its continuance to appear in all its magnitude. A man who becomes conscious of the responsibility he bears toward a human being who affectionately waits for him, or to an unfinished work, will never be able to throw away his life. He knows the “why” for his existence, and will be able to bear almost any “how.”

All of this is tied up with hope and ultimately survival. In the opening pages of the book Frankl talks about how he could tell from the faces of fellow camp inmates whether they would survive. If he could see hope on their faces he knew they had a chance of survival. If any signs of despair made themselves apparent Frankl knew these people would wither away without the precious resource of meaning in an environment that could not be endured if considered totally meaningless.

While trying to find the BI article again in order to write this post I ran across another related article. It appears Man’s Search for Meaning is headed for the silver screen. This makes me slightly depressed, because I don’t see how, or why, the book should be made into a movie. I can only see Hollywood making total schlock out of it.

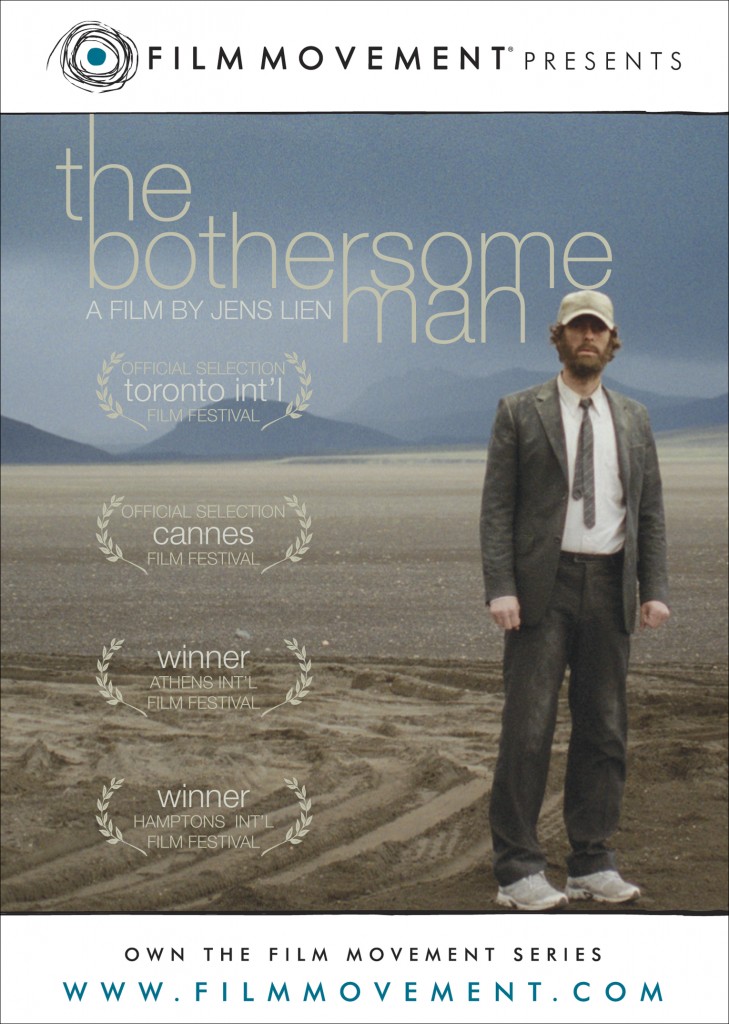

I might also be biased, because, as luck would have it, last night I unwittingly chose to watch the cinematic embodiment of Frankl’s philosophy in the Norwegian film The Bothersome Man. This film starts out with the inexplicable suicide of what seems to be a handsome and successful Andreas. The screen goes black, then he is transported into the moonscapes of the Norwegian countryside and ends up in an antiseptic looking city.

In this semblance of an afterlife he is immediately provided with everything a man might desire: home, job, friendly coworkers, girlfriend, mistress, and so on. Everything is geared to satisfy nearly all of his desires immediately, more often than not, before he asks. It is the Hallmark edition of heaven. There is one exception: None of this satisfies his desire for meaning. He begins to realize the food tastes all the same, then he starts noticing the superficiality of the relationships he has formed, and his work doesn’t make sense even if it pays well.

Nothing seems to be faithful to flesh and blood reality in the paradise of The Bothersome Man and therefore everything stands in the way of Andreas forging a meaningful narrative for his (after-)life. Despair overtakes him once he realizes this and he begins an amusingly (darkly) comic search for ways to dig himself out of his predicament. Even total annihilation after death would be preferable to such a life.

In the end, it becomes apparent that man cannot forgo his bothersome search for meaning. Without a “why” there is no “how.”

I should add: Movies also save us.

You might not be aware that Frankl’s wife was Catholic and he (himself Jewish) had at least one audience with Pius XII. The two men liked each other. Frankl even wrote some books bordering upon theology such as The Unconscious God.

I know it’s getting bothersome, but please donate some funds if you enjoy reading these posts through the button on this blog’s homepage. Feel free to donate in order to spite me as well–I won’t object.

In return I offer you this additional rare footage of Frankl lecturing on the meaning of life: