David Russell Mosley

Ordinary Time

9 August 2017

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dearest Readers,

Yesterday, in Ireland, Teachtaí Dála Danny Healy-Rae made the bold claim that the reason for the dip in Kerry Road was due to fairies. His argument actually extends back to 2007 when this first started happening. It seems, according to Healy-Rae, that what likely happened is some sort of Fairy Fort has been disturbed, causing the fair folk to take a certain level of retribution. At present, he has made no arguments for how to fix this problem, but is quoted as saying, “I have a machine standing in the yard right now. And if someone told me to go out and knock a fairy fort or touch it, I would starve first.”

This particular news story is quite similar to one from last year when an Icelandic road crew had to wash and re-stand an Elf Stone that had been knocked over during construction. This is, by no means, the first time, Icelanders have bent to the will of the Fair Folk, “In 1971 elves reportedly disrupted construction of a national highway from Reykjavik to the northeast. The project suffered repeated unusual technical difficulties because, it was claimed, elves did not want the large boulder that served as their home to be moved to make way for the new road.”

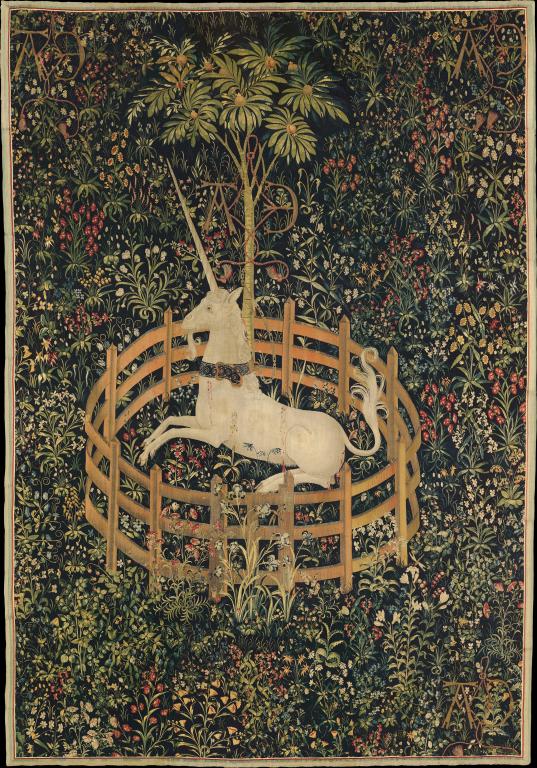

What I love about both of these stories is this: the end result of these beliefs in fairies and elves leads to better care for creation. Whether or not you personally believe in creatures like elves, goblins, fairies, and the like, you cannot deny that such belief often includes taking practical measures to protect nature. That is, in both instances, people, using folkloric, peasantish, knowledge react to disturbances in nature by righting wrongs. This has the benefit of leaving well enough alone whenever possible.

Tolkien as many now know, seems to have had some kind of a belief in fairies. There is a story that goes around about Tolkien carrying a leprechaun shoe in his pocket. More convincing, of course, is this from an early draft of his essay, “On Fairy-Stories:”

“Leaving aside the Question of the Real (objective) existence of Fairies, I will tell you what I think about that. If Fairies really exist––independent of Men––then very few of our “Fairy-stories” have any relation to them: as little, or less than our ghost-stories have to the real events that befall human personality (or form) after death. If Fairies exist they are bound by the Moral Law as is all the created Universe; but their duties and functions are not ours. They are not spirits of the dead, nor a branch of the human race, nor devils in fair shapes whose chief object is our deception and ruin. These are either human ideas out of which the Elf-idea has been separated, or, if Elves really exist mere human hypotheses (or confusions). They are a quite separate creation living in another mode. […] For lack of a better word they may be called spirits, daemons: inherent powers of the created world, deriving more directly and “earlier” (in terrestrial history) from the creating will of God, but nonetheless created, subject to Moral Law, capable of good and evil, and possibly (in this fallen world) sometimes evil” (254-255.Emphasis original).

Tolkien goes on to say:

“The tree-fairy (or a dryad) is, or was, a minor spirit in the process of creation who aided as ‘agent’ in the making effective of the divine Tree-idea or some part of it, or of even some one particular example: some tree. He is therefore now bound by use and love to Trees (or a tree), immortal while the world (and trees) last – never to escape, until the End” (254).

What I find so fascinating about this is not, so much, Tolkien treating fairies as real things, but the way he comes to associate them with nature and how that effects his understanding of nature. After all, if you believed that trees in general, if not trees in particular, were possessed of a dryadic spirit, you might not be so quick to chop them down, or at least to pay proper respect to the thing you’re chopping down. After all, Tolkien still wrote on paper, and yet believed trees to be of profound importance.

Lewis hits on a similar note in Perelandra when Ransom, his protagonist, encounters some kind of fairy or local god of the mountain in which he is traveling. Ransom is moved to this reverie:

“And it appeared to Ransom that there might, if a man could find it, be some way to renew the old Pagan practice of propitiating the local gods of unknown places in such fashion that it was no offense to God Himself but only a prudent and courteous apology for trespass” (158).

It is this idea that somehow, in someway, fairies–and Faërie in general–are connected to nature and that this ought to change the way we interact with nature. This is what I love about the Healy-Rae and Iceland articles. If, in someway as Lewis himself opines, we can find a way to respect nature so that it is no offense to God (in fact it would be to his glory) then maybe the result will not just be due deference given, but a better world for us to share with one another and whoever else may live here.

Sincerely,

David