Brian Godawa has now updated his post on the Noah serpent — twice! — in response to posts of mine in which I debunked the claim that Noah is Gnostic and tried to untangle just what the snakeskin represents, both in Judaism and within the film specifically.

Brian Godawa has now updated his post on the Noah serpent — twice! — in response to posts of mine in which I debunked the claim that Noah is Gnostic and tried to untangle just what the snakeskin represents, both in Judaism and within the film specifically.

Brian’s a good guy, and he’s done a lot of research into the Noah story, and I have found his posts on that subject very informative. But when it comes to his analysis of Darren Aronofsky’s film, it seems to me that he has certain blind spots, or that he insists too strongly on filtering his experience of the film through a certain worldview without fully engaging with the film on its own terms.

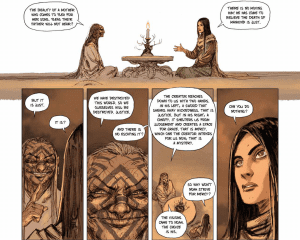

For example, two years ago Brian wrote a now-famous review of an early draft of the screenplay, in which Brian dubbed the title character an “environmentalist wacko”. When I read that same script a year later, I did not disagree with some of Brian’s criticisms, but I was struck by the fact that he had virtually ignored one of the most pivotal scenes, in which Methuselah spells out the film’s balancing act between divine justice and divine mercy. As it turns out, that bit of dialogue is missing from the actual film — perhaps the filmmakers thought it was too on-the-nose — but it was there in the script (it’s also in the graphic novel), and it seemed to me that any review which ignored this would be sorely lacking. So I wrote a blog post drawing attention to this scene.

For example, two years ago Brian wrote a now-famous review of an early draft of the screenplay, in which Brian dubbed the title character an “environmentalist wacko”. When I read that same script a year later, I did not disagree with some of Brian’s criticisms, but I was struck by the fact that he had virtually ignored one of the most pivotal scenes, in which Methuselah spells out the film’s balancing act between divine justice and divine mercy. As it turns out, that bit of dialogue is missing from the actual film — perhaps the filmmakers thought it was too on-the-nose — but it was there in the script (it’s also in the graphic novel), and it seemed to me that any review which ignored this would be sorely lacking. So I wrote a blog post drawing attention to this scene.

Now that he has seen the finished film itself, Brian dislikes it as much as he disliked the script, and that’s fine; as they say, there’s no accounting for taste, and there is plenty of room to talk about what works in the film and what doesn’t.

But last week he jumped on the “Noah is Gnostic” bandwagon and wrote a couple posts arguing that the film exalts both humanity and the serpent that tempted Adam and Eve over God, and in this I think he is very, very mistaken.

I’ll get to some of Brian’s points in a minute, but the simplest way to show how mistaken he is, is to point to the concluding summary of his latest response to me:

The Bible: Serpent bad, God good. God decides Man’s value.

Aronofsky’s Noah: Serpent good, God bad (and silent). Man decides Man’s value.

I would argue that God is not completely silent in this film — he does send dreams and visions, after all — but that’s a separate issue. The more pertinent question here is whether the film actually says that God is bad, and that the serpent is good. And I just don’t see how that reading of the film can be supported in any way whatsoever.

As I’ve said before, the second sentence in the film is “Temptation led to sin,” and this sentence is followed by images of violence and chaos that ultimately lead to (and deserve) divine judgment. More recently, the film’s co-writer Ari Handel has talked about how “the Tempter arose through” the serpent, causing the serpent to shed its luminescent skin and become a darker, more blatantly evil creature.

So with the film itself telling us that the serpent was responsible for all this evil, and with the filmmakers themselves telling us that the serpent was responsible for all this evil, how can we say that the film or its makers are actually saying the opposite? This makes no sense to me, unless we’re going to call the filmmakers outright liars.

Ultimately, the crux of arguments like Godawa’s (and Brian Mattson’s) seems to be that they don’t like the scenes with the snakeskin, which is shed by the serpent in the Garden of Eden and is treated like a sort of holy relic by Noah and his family.

I admit, I kind of recoiled at this imagery myself the first time I saw the film. Or maybe it would be more accurate to say that I was puzzled by it. Unlike the two Brians, whose first instinct seems to have been to read all sorts of assumptions into that imagery, my first instinct was to wonder why the filmmakers had put those scenes in there — especially since those scenes weren’t in the early script that Godawa and I had read, and they didn’t seem to add all that much to the story.

Alas, I neglected to ask Aronofsky and Handel about the snakeskin when I interviewed them — there were so many other topics to discuss, and since the interview began mere seconds after the screening came to an end (I spoke to them in the very same screening room where I had just watched the film), I didn’t have a chance to check my notes or to adjust the list of questions I had compiled before the screening.

But a colleague of mine who spoke to them some time later did raise this question, and told me that the skin was meant to represent the serpent’s original goodness. And now Handel is on record to that effect in his recent interview with Relevant magazine.

Handel’s comments prompted me to do a bit of research, and I found that there are multiple sources in the Jewish tradition which hypothesize that the “garments of skin” worn by Adam and Eve when they were cast out of Eden were made from a skin shed by the serpent. Some of those sources even dwell on the paradox that a skin shed by the Tempter should be the means by which Adam and Eve were able to preserve some of their human dignity. (I discuss this in an addendum to one of my earlier posts.)

The filmmakers take this idea even further and suggest that the serpent shed the skin at the very point when it turned to evil, thus, the serpent loses its “garment of light” just as Adam and Eve will lose theirs when they eat the forbidden fruit. (And please, no more nonsense about the “garments of light” being some sort of evil Gnostic-Kabbalistic heresy. The tradition that Adam and Eve were clothed in “garments of light” before they fell is accepted within my own Eastern Orthodox tradition.)

So, I came away from the film with a question, and now I have an answer; indeed, I have learned something that I didn’t know before. The two Brians, on the other hand, did not come away with questions; they assumed that they already knew what the answer would be. And this has coloured their commentary ever since.

This, it seems to me, is just one more example of how some viewers are judging this “most Jewish” of Bible movies according to Christian presuppositions.

Brian does not dispute the fact that Jewish tradition posits all these ideas about the snakeskin; instead, his main rebuttal is to say that the Christian tradition is better than the Jewish tradition, and more authentically Jewish than the Jewish tradition.

Be that as it may — and setting aside the fact that the first-century Judaism which led to modern Christianity and modern Judaism was so diverse that some scholars are wont to speak of Judaisms, plural, in this period — my point here is not to say that I think the Jewish tradition is better than the Christian tradition or vice versa.

My point, rather, is to say that this film grows out of the Jewish tradition, and that it needs to be understood within that context if it is to be understood at all. As I wrote last year in an article on the Bible-epic revival for The Anglican Planet:

Second, we should recognize that not all of these stories are necessarily “ours.” The biblical story of Noah, for example, is as much a part of the Jewish scriptures as it is ours, and it seems Aronofsky’s film will be based in part on the pseudepigraphal Book of Enoch and other Jewish legends that elaborate on that narrative. Christians can, at least in theory, benefit from these traditions as surely as non-Catholics benefited from Mel Gibson’s deeply Catholic treatment of the Passion.

I’m sure there were probably some Protestants a decade ago who objected to the levitating cross and the mystical depiction of Mary and some of the various other things that Mel Gibson put into his film, all of which reflect an utterly non-Protestant sensibility. But by and large, evangelical Christians seemed to be okay with that film, and some of them were perhaps even willing to learn a thing or two about the Catholic tradition and what it can teach us about the death of Jesus.

I’m sure there were probably some Protestants a decade ago who objected to the levitating cross and the mystical depiction of Mary and some of the various other things that Mel Gibson put into his film, all of which reflect an utterly non-Protestant sensibility. But by and large, evangelical Christians seemed to be okay with that film, and some of them were perhaps even willing to learn a thing or two about the Catholic tradition and what it can teach us about the death of Jesus.

Similarly, I think we should be able to approach a film like Noah in a spirit of honest curiosity. We don’t have to agree with everything the film says and does, and we don’t have to give up any of our Christian beliefs about Creation, the Fall, the Flood and so on. But we do a disservice to the film and to everyone who is trying to understand it when we try to shoehorn it into categories that it was never meant to fit into.

As for the question of God’s silence, or the fact that Noah assumes some of the functions within this film that the Bible ascribes to God (choosing between justice and mercy, blessing his offspring, etc.)… I will try to address that in another post.