One night during my freshman year of college, a friend of mine and I were discussing the bitter breakup of Prince Charles’ and Princess Diana’s marriage. My memory is hazy as to the beginnings of this conversation, but I clearly remember confidently saying to her that religious Muslim men would never hit their wives. Before I could go on on, she cut me off by saying, “My father is religious and he used to beat my mother.”

One night during my freshman year of college, a friend of mine and I were discussing the bitter breakup of Prince Charles’ and Princess Diana’s marriage. My memory is hazy as to the beginnings of this conversation, but I clearly remember confidently saying to her that religious Muslim men would never hit their wives. Before I could go on on, she cut me off by saying, “My father is religious and he used to beat my mother.”

My comment to my friend reflected my naivete. While the community I was raised certainly had it’s share of abusive men, Teenaged-Me dismissed them because they were mostly liquor store owners and therefore (in my black and white mind), not religious. Religious men would never condone violence against women, much less perpetrate it, I’d believed, universalizing my own familial experiences. I was rudely awoken by my friend that night and I like to think that I am not so naive any more.

Her comment shocked me because I’d been raised in a loving, warm environment by two parents who loved and respected each other. I have never, ever seen my late father – a deeply religious man who was politically aligned with the faith-based opposition – ever raise his hand against my mother or my sister and me. I couldn’t even fathom it. He was a man who treated women respectfully: from his illiterate, elderly mother, to his well-educated and bilingual wife, and his bicultural American teenaged daughters, as well as his sisters and many nieces, his colleagues and strangers, the young or old, Muslim women and non-Muslim. I’ve literally never seen or heard my father disrespect any female verbally, much less attack one violently.

In my estimation, my father was the epitome of the perfect Muslim man. And indeed, he was my first Muslim male ally. My father suddenly passed away at the age of 54 after a routine surgery. A few days before his passing, my sister commented to me, “We have the nicest father, mashallah. We are so lucky.” We didn’t know that we would lose him in in just a few days, but the legacy of his behavior, humility and attitude toward not only women and girls, but to all of God’s creation, has remained the most salient example of what Islamic adab (etiquette) should be. Adab is known by the refinement, good manners, morals, decorum and decency of a person. I’d always been taught that a good Muslim always exuded adab in every situation, especially difficult ones.

Unfortunately, I was not surprised to read the cheesy, adab-less and misogynistic tweets of a widely known British instructor affiliated with Al Maghrib Institute on International Women’s Day this week. You can read his original posts and his subsequent self-defense posts, in which he “jests” about encouraging his male followers to rape, assault and mutilate women and girls in this powerful piece by Patheos blogger Rabia Chaudry. By now, I know that there are plenty of religious Muslim men who don’t respect Muslim women as full adults, and equal partners in enjoining good and forbidding evil.

I was dismayed, however, at his defense mechanism, which seemed to consist of him repeatedly saying that his criticizers don’t have a sense of humor, don’t know who he “really” is, hate his organization, are enemies of the faith and so on. He did sort of apologize (it was one of those “if you were offended by my words, I’m sorry” faux-pologies), but it seems that he is digging his heels in. Some of the leaders at Al Maghrib have put out public statements about this controversy with a lot more adab than any of his comments. However, it seems that they are closing ranks around their colleague and are so far refusing to officially distance the organization from his repugnant and hurtful words, which is highly unfortunate for several reasons.

Though the instructor’s original International Women’s Day posts were dumb, they were not morally repugnant. His hateful, “jokey” defense mechanism, however, was beyond the pale. There are topics that should be beyond the scope of acceptable “jokes” within the context of Islamic educational institutions. Rape, physical assault and female genital mutilation are some of these topics because these are real issues that real Muslim women and girls endure today and joking about them triggers trauma and pain to survivors and their loved ones. It would not decrease his reputation for the instructor to simply say, “I recognize that my words were hurtful, though that was not my intent. I apologize for the hurt I’ve unintentionally caused full stop.” In fact, it would only increase his character. He could indeed become a genuine ally to Muslim women.

I’ve written before about the adab of online activism; a concept I think about a lot as the curator of Side Entrance, a site that highlights positive and negative women’s spaces in mosques around the world. I have gotten negative feedback saying that I’m airing dirty laundry and that using social media to call out these mosques is rude. I look at social media as a starting point for public conversations, which raise awareness about challenges we are facing, which can then lead to action on the ground. I assume this understanding is shared by religious leaders who maintain public profiles on various social media platforms. The thing about social media is that it is public. You are not sharing your views in a safe space. Your words or pictures may be seen by those who have a painful relationship with the topic you are discussing. Social media is also often the space where people whose voices are marginalized by the mainstream find an outlet. Because of all these reasons, one must maintain a certain adab in their social media output, whether one is genuinely trying to raise awareness of an issue, challenge certain norms that hurt a subset of people, educate on a certain topic or share a joke with followers.

While there are folks out there who have a particular agenda against Al Maghrib, many of the women (and men) who were deeply insulted by these comments do not want to see the destruction of this esteemed institution. These are people who believe that our brothers should also speak up and speak out when Muslim women are being belittled and vilified – even and especially when it is other Muslim men who are doing the belittling and vilifying. By skirting around the issue and asking people to forgive their instructor without real, public apology from him, Al Maghrib risks being seen as an organization that does not ally with, nor take seriously, women who are re-experiencing real trauma from situations they’d previously survived, because of the words of this teacher affiliated with their organization.

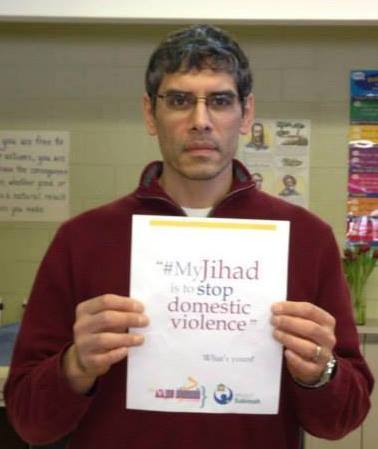

The situation is ugly. I can’t sugarcoat anything out of this mess. To be honest, I didn’t even want to dive into it. We are constantly bombarded with stories of Muslim men hurting Muslim women. In the case of the Al Maghrib instructor, yet another reason why his words were so hurtful is that they also mock the fact that Muslim men are constantly being painted as violent and misogynistic. Since I’d already been in the habit of using the hashtag #MuslimMaleAllies to refer to men who are supportive of equitable women’s spaces in mosques, I thought it could foster a more constructive conversation. So I simply asked women to share stories that honor Muslim men and boys who support the women and girls in their lives.

The situation is ugly. I can’t sugarcoat anything out of this mess. To be honest, I didn’t even want to dive into it. We are constantly bombarded with stories of Muslim men hurting Muslim women. In the case of the Al Maghrib instructor, yet another reason why his words were so hurtful is that they also mock the fact that Muslim men are constantly being painted as violent and misogynistic. Since I’d already been in the habit of using the hashtag #MuslimMaleAllies to refer to men who are supportive of equitable women’s spaces in mosques, I thought it could foster a more constructive conversation. So I simply asked women to share stories that honor Muslim men and boys who support the women and girls in their lives.

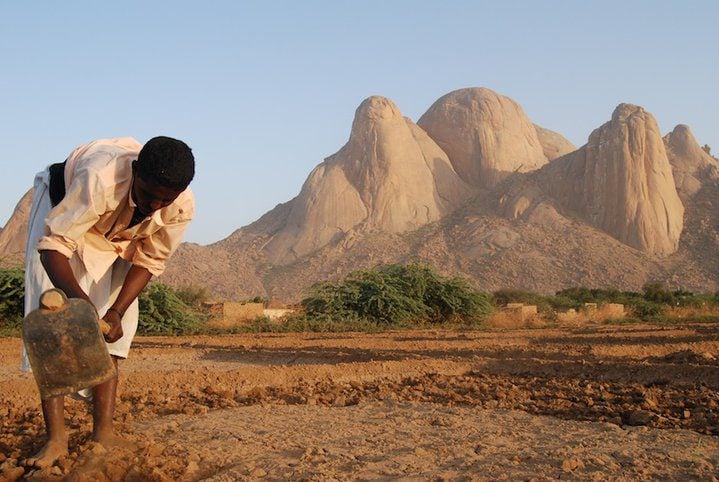

The stories have poured in, from short tweets, to longer posts on Facebook and in personal emails. We are reminded of Divine wisdom from the Quran and of the Prophetic example. We are learning of fathers who supported their daughters in leaving abusive marriages. We are hearing from scholars who admonish men who don’t take care of widows. We are honoring men who support the education of their wives, daughters, sisters, nieces and granddaughters. We are sharing stories of male-led initiatives against domestic violence. We are hearing about husbands who participate fully in child-rearing and housekeeping. In this Women’s History Month, we are highlighting supportive Muslim men, from our beloved Prophet Muhammad PBUH, to our brothers in faith today. They are inspired to support the women and girls in their lives because of their faith, not despite it. They interact lovingly with their relations and with the utmost adab with their sisters in faith. And as long as the Prophetic tradition lives, as long as there are stories of genuine Muslim male allies like my beloved father, I will never believe that the Al Maghrib instructor’s repugnant views toward women are normative for all my Muslim brothers.

For all my sisters who are suffering abuse under the hands of the men in their lives, I offer the English translation of one of the most powerful supplications I know, the Prayer of the Oppressed.