This post gives a number of suggestions for learning and teaching theological concepts in Chinese. However, many of the ideas below could easily be applied to other languages as well.

This post gives a number of suggestions for learning and teaching theological concepts in Chinese. However, many of the ideas below could easily be applied to other languages as well.

In the last post, I explained three of the most critical suggestions. Today, the list is more straightforward, starting with tip #4.

4. Use Flashcards

No one “likes” doing flashcards. However, they are indispensable for establishing a firm foundation and easily recalling many theological words and concepts. After all, few people go out everyday to the market and talk about propitiation, covenants, and election. You have to do whatever it takes to keep theological words fresh, since you never know where a theological discussion might take you.

Anki is a popular tool for systematically reviewing flashcards in a ways that staggers you rate of review. Anki has an app as well as a web-based tool.

4. Improving Your Listening

Go online and listen to Chinese sermons. Besides using a web search, iTunes can help you find podcasts and lectures (using iTunes U).

Also, find a local small group Bible study. This will help you grasp more colloquial ways of speaking about various subjects. However, beware that you don’t get sucked into leading the Bible study before you are ready. Go to listen and learn. As you are able, you can participate more and more.

5. Characters in the New Testament

As you learn to read (or write) characters, prioritize your learning by studying them in frequency order. I previously posted an exhaustive list of every character in the Chinese New Testament (CUV, 和合本) in frequency order.

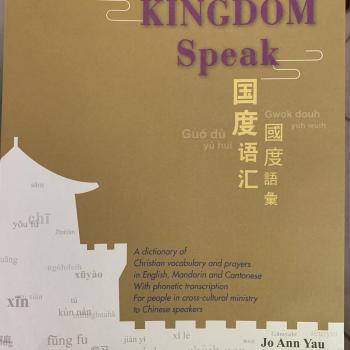

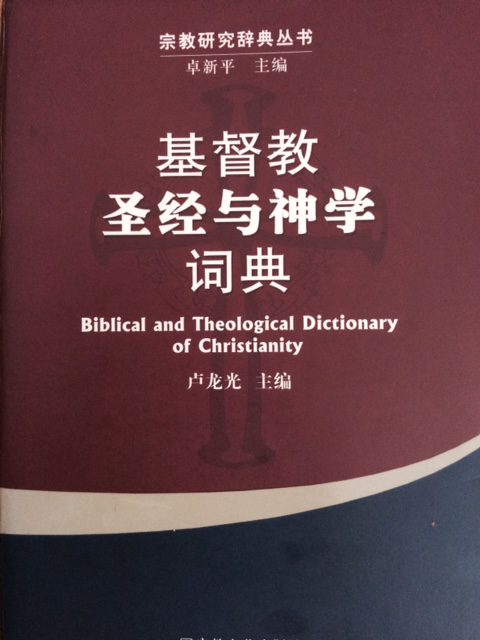

6. Theological Dictionary

6. Theological Dictionary

Invest in the Biblical and Theological Dictionary of Christianity (宗教研究辞典丛书 ; 宗教研究辞典丛书). Few people know about this resource. It exists in both simplified and complex characters. It was published in 2007 by 宗教文化出版社.

7. Use PPT

Using Powerpoint, Keynote, or similar programs enables you to help people see the characters that you are speaking. Perhaps, the sound you are saying could refer to multiple characters. Or, your pronunciation or tones may be a little off.

8. Preview Key Ideas

In school, Chinese rely on memorization more than analysis. Consequently, they sometimes struggle to track with logical arguments or presentations with interconnected layers. Therefore, I suggest previewing the key ideas of your presentation in advance. This gives them enough context to understand your meaning (especially since you are speaking in your second language).

9. Practice with a tutor.

This is a no-brainer. However, there is another reason (besides language fluency) to practice with a tutor. A tutor can help you anticipate people’s questions and understand how Chinese might “hear” you as you explain a theological idea. He or she can also give you relevant Chinese background or even idioms that will assist your teaching.

You shouldn’t be surprised if your tutor settles for a word saying it’s “good enough.” Don’t accept “good enough.” After all, your tutor might not fully grasp all you mean by a given concept. Also, different words carry a variety of connotations. Dig deeper to find just the right word or structure to help learners understand and retain what you teach.

10. Paste all biblical texts in two languages

You don’t want to use brain cells to flip back and forth between your notes and your Bible, especially when you are using two languages to think and speak. By including both the English and the Chinese in your notes, you can very efficiently read a passage or perhaps compare the English/Chinese/Greek/Hebrew.

One more related note. In order to give yourself a rest, you may want to let your students read aloud the biblical texts. Speaking for long periods of time in a second language can be tough on the throat and body.

11. Read your notes

It’s ok to read your notes, particularly early in the process and especially as a foreigner. Don’t forget that their teachers routine read in a monotone voice from a set script. Of course, I don’t encourage you to drone on in a disengaged fashion. My point is simply that you don’t have to deliver a “TED talk” whenever you teach.

Clarity is more important than fluency.

12. Use pinyin in class

Finally, I know most foreigners are not proficient at writing characters. Therefore, if you need to do so, don’t hesitate to use pinyin when explaining concepts on a white board. Most Chinese know or are very familiar with pinyin. Even if a pinyin word or phrase at first is unclear to them, they will know what you mean when you say the word.

Of course, it would be great to be able to write every character. But we live in the real world. We all have to make decisions about the skills we master with the time we have. I would never discourage someone from learning to write 汉子; yet, you don’t want to wait to teach until you “know it all.” In the meantime, do what you can and continue to develop your language skills.

Photo Credit: SamHakes via morguefile.com