John Sanders says all theology is embodied. On the surface, this doesn’t seem noteworthy. People for many years have aspired to “embody the gospel.” However, this is not Sanders’ meaning.

His recent book Theology in the Flesh: How Embodiment and Culture Shape the Way We Think about Truth, Morality, and God (2016) will be a game changer for many people. Sanders explains why cognitive linguistics is so significant for biblical interpretation and theological discourse.

With terms like “embodiment” and “cognitive linguistics,” one might suspect the book is too abstract or erudite for non-specialists. No true. Sanders’ argument is immensely practical; his explanations and examples are concrete and common.

Theology is Limited by Thinking

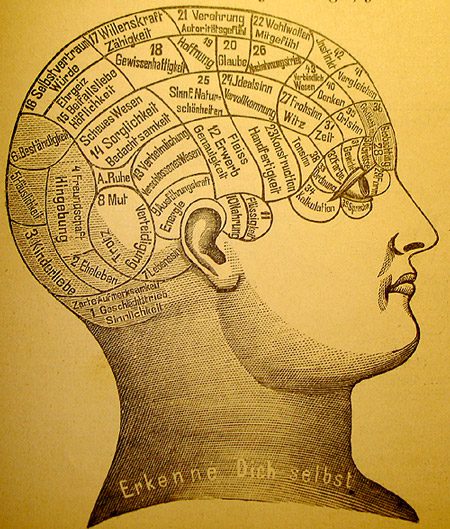

Sanders’ basic thesis is that all theology is “based upon the cognitive processes available to humans” (p. 23). He spends most of the book illustrating and applying this insight, which influences our understanding of truth, meaning, morality, various doctrine, and even our views about God. For some, his point will seem mundane, but the implications are massive.

Consider the significance of these two basic claims:

- “We use our everyday conceptual structures to think about God and religion” (p. 5).

- “Culture plays an important role in the construction of meaning” (p. 6).

While finding the first statement uncontroversial, many people get nervous about the second claim, despite the fact it is logically follows from the first.

Let’s clarify what he means by the first statement.

He explains, “Human cognition is dependent upon embodied human experiences” (pp. 20–23). By this, he means people cannot perceive or conceive of anything that does not stem from embodied experience. Our five senses and our perception of time, for instance, both make possible and constrain our ability to think about truth, meaning, and the Bible.

Imagine we are jellyfish. In that case, “We would not, for example, have the concept in front of since jellyfish have no faces nor would we use seeing or hearing to mean understanding something.”

By implication, “all human understanding is perspectival” (pp. 23–25).

But Sanders anticipates reader concerns:

“This book is opposed to absolute relativism. There is truth and correct belief, but we typically cannot demonstrate the truth of our convictions in such a way that convinces everyone.” (p. 8)

He reinforces the point later.

“There is a real world that exists independently of us, but our understanding of it is shaped by our embodied minds. Some mistakenly interpret this situation to mean nothing can be said about objective truth or that the existence of God is now out of the question. [Rather] our understanding of God and truth will be dependent upon our limited embodied cognitive processes.” (pp. 24–25)

Although this point should be common sense (i.e. all understanding depends on and is limited by one’s perspective), many Christians hesitate to admit it. Few people take practical steps allowing it to shape how they theologize and contextualize.

A Relative Perspective on Absolute Truth

Sanders highlights an idea long ignored by the church: God’s people have a relative perspective on absolute truth.

By acknowledging this fact, we can seize several opportunities. Sanders’ comments simply reinforce much of what I have argued about contextualization. I’ll list three areas affected by the book’s basic thesis. (Later posts will explore other aspects of Sanders’ argument.)

1. Humility

If the book does anything, it should foster humility in readers. I don’t refer to a false wishy-washy humility that lacks conviction about truth. Instead, people need to realize that cultures and churches use different metaphors and concepts available to them from their experiences. For example…

Morality

One group might use the Moral Accounting metaphor whereas another conceives of Morality as a Journey (pp. 141–44). Both are legitimate conceptions of morality but each functions differently to guide moral thought.

Truth

Truth as an Object is a common metaphor (“We have the truth”). But the Bible also presents Truth as a Guide, as when we should “follow the truth wherever it leads” (pp. 81–83). Also, we are to “do the truth” (John 3:21), “walk in truth” (2 John 4). Jesus himself said, “I am the truth” (John 14:6).

We need humility to listen and embrace the full range of ways people talk about the world, rather than play one against the other.

2. Hermeneutics

This fact––that human cognition is based on our embodied experience––has countless implications for biblical interpretation and theology. Here are a few broad strokes:

Limits: Our perspectives on Scripture are limited (though not necessarily wrong).

Diversity: Biblical truth is expressed in diverse ways, many of which may be less familiar to us and our culture.

Layers: Any given passage might have layers of interwoven meanings.

Accessibility: Biblical truth is accessible to people across cultures and ages, though not equally so, depending on varying experiences and cultures.

Meaning: The line between “literal” and “metaphorical” is often a mirage (pp. 121–29).

3. Homiletics

Our teaching and preaching ought to account for the fact that humans are dependent on context and experience to understand meaning. Metaphors are so common within human cognition partly because we rely on concrete experience to understand abstract ideas.

By implication, we should give more attention to the value of biblical theology and storying. Missionaries and pastors over rely on systematic theology to provide quick, short answers to people’s questions. All the while, the Bible increasing feels more removed from people’s lives.

In coming posts, we’ll specifically look at the significance of “frames” and metaphors for our ministries.