Re-visioning the Grand Narrative of the Bible

Re-visioning the Grand Narrative of the Bible

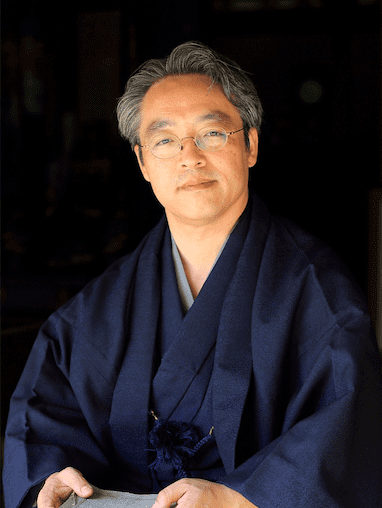

By Kaz Yamazaki-Ransom, a Japanese New Testament scholar. He earned his Ph.D. from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, and his dissertation was published under the title The Roman Empire in Luke’s Narrative (T&T Clark International, 2010). His works have been published in English, Japanese, and Korean, including two entries in the second edition of Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels (IVP, 2013). His research interests include Luke-Acts, narrative criticism, the New Testament and the Roman Empire, and the use of the Old Testament in the New. He is president at Revival Biblical Seminary in Aichi, Japan and the chair of the Japan Evangelical Theological Society, Central Japan Chapter. He blogs in Japanese at “Through a Glass” (1co1312.wordpress.com). He currently lives in Aichi, Japan with his wife, Doria, who is American, and their three teenage daughters.

In recent years more and more Evangelicals approach the Bible as a single narrative, not as an encyclopedia, a theology textbook, or a moral rulebook. The overarching story of the entire Bible is called its “grand narrative” or “metanarrative.” This is the basic story that gives every portion of the Bible its proper meaning. Postmodern skepticism about metanarrative notwithstanding, many Evangelicals find the idea helpful for understanding the nature and authority of the Bible.

Every narrative has a plot, a storyline that is a series of events arranged in a meaningful order. But there are a variety of ways to understand the actual form of the storyline of the Bible. I remember when one of my professors in seminary told his students that he would divide the entire Bible into three parts: Genesis 1-2 (Creation), Genesis 3 (Fall) and the rest of the Bible (Salvation). Simple enough.

Others have proposed a four-part model of the storyline of the Bible:

- Creation

- Fall

- Redemption

- Restoration

And of course we have the well-known five-act drama model of N.T. Wright:

- Creation

- Fall

- Israel

- Jesus

- Church-Eschaton

Still others have proposed a six-part model, basically splitting Wright’s fifth act into two:

- Creation

- Fall

- Israel

- Jesus

- Church

- New Creation

Up until now, I have employed this six-part model to understand the grand narrative of the Bible, but I would now like to revise this model even further. I propose the following seven-part model:

- Creation (A)

- Origin of Evil (B)

- People of God (Israel) (C)

- Jesus (X)

- Renewed People of God (Church) (C’)

- Defeat of Evil (B’)

- Renewed Creation (A’)

As you can see, this new model is basically the same as the six-part model, but I inserted an additional chapter or act (however you choose to refer to it) as the sixth part, the Defeat of Evil.

This gives a concentric structure to the entire storyline of the Bible:

Since this kind of symmetric (sometimes called “chiastic”) structure frequently appears in the Bible, it seems quite appropriate to see the entire storyline of the Bible in this way. And of course the number seven often symbolizes perfection in the Bible.

But most importantly, this structure places the narrative of Jesus Christ at the very center of the storyline of the Bible. The German New Testament scholar Hans Conzelmann once argued that Luke’s understanding of salvation history is threefold: the time of Israel, the time of Jesus, and the time of the Church. He then called the time of Jesus “Die Mitte der Zeit (the center of time).” I have a number of problems with Conzelmann’s overall arguments about Lukan theology, but I can wholeheartedly agree that Jesus Christ is the “center of time” in the grand narrative of the Bible.

The Christ event is the definitive turning point of the grand narrative of the Bible. God’s work of renewing everything started with the cross and resurrection of Jesus. This renewal began first with the renewal of the people of God (chapter 5 or C’): the people of God are no longer defined as ethnic Israel but as the community of people—with various ethnic origins—who acknowledge the lordship of Jesus Christ. But that’s not the end of the story. God’s work of renewal will eventually cover not only humanity but the entire creation (chapter 7 or A’) (Rom 8:19-22; Rev 21:1-5). All this starts with Jesus, as Paul says: “Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, the new creation has come: The old has gone, the new is here!“ (2 Cor 5:17).

Now, the most obvious change I propose to the six-part model is that I have added an additional element, the Defeat of Evil. This sixth part of the grand narrative includes the second coming of Christ, the last judgment, and the final victory over all evil (1 Cor 15:23-28; Rev 19-20, etc.). Of course, these events are implicitly included in the other models as part of the eschatological consummation. However, there are two reasons why I have made this a separate part.

First, the New Testament depicts the final defeat of evil not merely as the climax of the era of the church, but as a distinct series of events initiated with the second coming of Christ. It is also distinguished from the creation of the new heaven and new earth, because the defeat of evil is not in itself a part of the new creation but a necessary preparation for it. Thus it seems appropriate to assign a separate chapter to these events.

More importantly, this sixth part of the grand narrative corresponds to the second part, the Origin of Evil. Usually the second part of the grand narrative of the Bible is called the Fall, but this designation tends to cause people to think solely about the fall of humanity. The story of Adam and Eve in Genesis 3 is usually associated with this part. To be certain, the fall of humanity has a central importance in the grand narrative of the Bible, but that is not the only thing going on here.

When we look at the third chapter of Genesis, the first character to appear in the story is neither Adam, nor Eve, nor God—it is the serpent who tempts Eve (and Adam) to disobey God’s command. So the story presupposes that, when humans first sinned and rebelled against God, there were already other creature(s) who had rebelled against God and who were bent on destroying his creation.

The Bible repeatedly talks about supernatural adversaries against God. Their existence is indicated in such Old Testament passages as Genesis 6:1-4; Psalm 82; Isaiah 24:21-22; and Daniel 10:13, 20. The New Testament places a great emphasis on Satan and demons as the enemies of God and the church. It is not my purpose here to discuss the origin of these supernatural evil beings, but my point is that the fall of humanity must be seen against the backdrop of a larger rebellion against God. This is the reason I call the second chapter of the grand narrative the Origin of Evil, not just the Fall.

This becomes important when we think about the sixth chapter, the Defeat of Evil. The series of events that will happen between Jesus’ second coming and the new heaven and new earth deals not only with the final judgment of humanity—important as that is—but also with the judgment of Satan and all spiritual adversaries. In fact, the Bible frequently combines these two topics. In Revelation the final judgment of humanity (20:11-15) is told side by side with the judgment of Satan, the Anti-Christ, and the False Prophet—the so-called “Evil Trinity” (19:20; 20:10). In the parable of the sheep and the goats in Matthew 25, Christ, when he comes again, tells the sinners, “‘Depart from me, you who are cursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels.’” (Matt 25:41). Here again, the judgment of humans is connected with the judgment of evil angels. Thus, what happens in the sixth chapter of the grand narrative deals not only with the final judgment and salvation of humanity but with the final defeat of all evil (1 Cor 15:23-28).

Now, the plot of most narratives involves a certain problem or conflict. The pattern of the problem and its solution is the basic driving force that moves the story forward, like this:

This pattern also applies to the grand narrative of the Bible. The major problem in the Bible is that, although God created the world as something good (A), evil emerged in the world (B). This is a problem on a cosmic scale, including but not limited to the fall of humanity. As a result, not only was humanity isolated from God, but the entire “creation was subjected to frustration” (Rom 8:20).

God works to solve this problem and to save humanity and restore the cosmos. This is done through the people of God on earth (C –> C’) with the cross and resurrection of Jesus at their center (X). When the age of the church comes to its conclusion, Christ comes again and the problem of evil is finally solved (B’). As a result, God forever reigns in the new heaven and new earth, which is free from all evil (A’). Thus the above scheme looks like this:

As can be seen, the final solution God has for the problem that is plaguing this world (B’) corresponds to the original problem (B) in its depth and scope in that it deals with all the evil in the world, not just human sin. I would like to emphasize that this does not downplay the importance of the fall and redemption of humanity, which is the central thread of the grand narrative of the Bible. These must, however, be seen against the larger backdrop of the problem of evil in this world.

The story of the Bible is not a narrative that is limited solely to humanity. It is the great cosmic drama that involves all of creation, a chiastically perfected story revolving around the central figure of all history: Jesus Christ.

[I first published this essay on my Japanese blog, but as I was finalizing the English version, I happened upon a recent blog post by Jackson Wu. He also proposes a chiastic structure for the grand narrative of the Bible. As I do, Wu places the Christ event at the center of the chiasm (not surprising!), but he proposes a nine-part rather than a seven-part structure, and his take on many elements of the grand narrative is different. His configuration focuses more on the covenantal history of Israel, while I emphasize the cosmic-scale significance of the origin and defeat of evil. My proposed structure further develops the formulations of the grand narrative of the Bible presented by N.T. Wright and others, as shown above. But I am pleased to find that someone else (and a fellow Asian scholar, at that!) has thoughts similar to mine. Also, Wu’s explanation about the nature and function of chiasm in ancient literature is excellent.]