By my friend Allan Bevere:

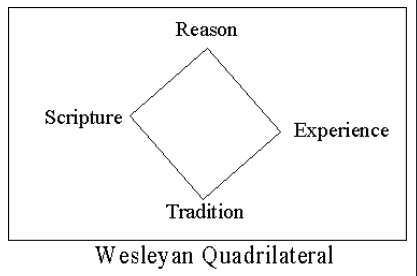

In this post, I am not really offering any new insights or a new perspective. But I decided to post on this subject because I think it is important to make the case once again that the so-called Wesleyan Quadrilateral (as has been said many times) is neither Wesleyan nor a quadrilateral, even though we UMs continue to employ it. The fact that we do so reveals we are much less Wesleyan than we in actuality affirm.

In this post, I am not really offering any new insights or a new perspective. But I decided to post on this subject because I think it is important to make the case once again that the so-called Wesleyan Quadrilateral (as has been said many times) is neither Wesleyan nor a quadrilateral, even though we UMs continue to employ it. The fact that we do so reveals we are much less Wesleyan than we in actuality affirm.

For those not versed in the Wesleyan Quadrilateral, the following definitionis helpful:

The phrase which has relatively recently come into use to describe the principal factors that John Wesley believed illuminate the core of the Christian faith for the believer. Wesley did not formulate the succinct statement now commonly referred to as the Wesley Quadrilateral. Building on the Anglican theological tradition, Wesley added a fourth emphasis, experience. The resulting four components or “sides” of the quadrilateral are (1) Scripture, (2) tradition, (3) reason, and (4) experience. For United Methodists, Scripture is considered the primary source and standard for Christian doctrine. Tradition is experience and the witness of development and growth of the faith through the past centuries and in many nations and cultures. Experience is the individual’s understanding and appropriating of the faith in the light of his or her own life. Through reason the individual Christian brings to bear on the Christian faith discerning and cogent thought. These four elements taken together bring the individual Christian to a mature and fulfilling understanding of the Christian faith and the required response of worship and service.

Of course, the problem with this definition is that it does not in and of itself affirm a quadrilateral. If Scripture is “considered the primary source and standard for Christian doctrine” then it simply cannot occupy one side of a four sided shape. The quadrilateral gives the false impression that Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience are four equal components in determining what is authoritative for the church. Moreover, what too often happens in UM circles is that when the quadrilateral is employed, it is most of the time used for the purpose of pitting one of the four “principal factors” against the others (usually to pit experience against Scripture).

American Methodists tend to balk at a full embrace of doctrine because they’ve always tended to be more American than Methodist. In popular American culture, anything that gets in the way of unlimited freedom of individual action or opinion is seen as, well, un-American. Thus Christian discipleship must always conform to what good, consumer-oriented and radically democratic Americans think it should.

That idea would strike John Wesley as bizarre. After all, his agenda at the first annual conference in 1744 was centered on considering the questions, What should we teach? How should we teach it? And what should we be doing, practically?

…scripture, tradition and reason are not like three different bookshelves, each of which can be ransacked for answers to key questions. Rather, scripture is the bookshelf; tradition is the memory of what people in the house have read and understood (or perhaps misunderstood) from that shelf; and reason is the set of spectacles that people wear in order to make sense of what they read– though, worryingly, the spectacles have varied over time, and there are signs that some readers, using the “reason” available to them, have severely distorted the texts they were reading. “Experience” is something different again, referring to the effect on readers of what they have read, and/or the worldview, the life experience, the political circumstances, and so on, within which that reading takes place (The Last Word).

“Experience” is far too slippery for the concept to stand any chance of providing a stable basis sufficient to serve as an “authority,” unless what is meant is that, as the book of Judges wryly puts it, everyone should simply do that which is right in their own eyes (The Last Word).