The folks at the Atheo paganismwebsite have weighed in on my You Can’t Practice Paganism While You Look Down Your Nose At It exchange with John Halstead. Their title is The Religion that Dares Not Speak its Name – it’s a mixture of good observations, let’s-get-along suggestions, and a few mischaracterizations that some will take offense with.

I see no need to defend the honor of theistic Pagans – such rebuttals are rarely helpful in the grand scheme of things. But I do want to address one issue the Atheopagan writer raised at the end of his post:

Here’s a suggestion: start prefacing those declarative sentences about your gods with “I believe”. I’ll do the same with what I believe…and don’t.

I think that if we get in that habit, we can get along much better.

On the surface that seems like a reasonable request. But it’s not – it’s a recipe for turning your religion into empty words.

Let me point you to this excellent piece by Yvonne Aburrow titled Faith and Belief. Yvonne explores the roots of these words and how their meaning has changed over time. Read the whole thing – here’s a key quote:

To believe in something in the original sense is to prize it, to value it, to hold it dear. Do you prize your Pagan practice, your relationship with the gods? Do you hold dear the culture and values of Paganism? Then you believe in them.

In that sense I enthusiastically say “I believe in the Gods.” But in our Protestant-dominated mainstream culture, belief is assumed to mean the acceptance of the literal truth of an unprovable proposition. In the atheist-influenced reaction to this culture, that acceptance is assumed to be a bad thing, or a least an unsupported and likely unjustified conclusion.

So when you qualify your religion with the disclaimer “I believe” you’re saying you’re not sure about it.

Now, it’s good to be humble about your religion. Religion deals with mysteries and with questions of ultimate truth and ultimate reality. Brilliant philosophers and theologians have struggled with these questions for thousands of years and have come up with widely differing ideas. To think we have the One Right Answer is at best naïve, if not downright arrogant.

But there’s a time and place to be humble, and there’s a time and place to be confident.

But there’s a time and place to be humble, and there’s a time and place to be confident.

Nobel prize-winning author Thomas Mann said “a myth is a story about the way things never were but always are.” All of us who read or watch films understand the power of a good story: the power to make us think and feel, and when the story is strong enough, the power to change our lives. One of the marks of a good story is that we’re absorbed in it, identifying with characters and circumstances.

One of the marks of a bad story is that we’re continually reminded that it’s a story. Ridiculous dialogue, lifeless acting, and low production values can kill a movie, even if the story it’s trying to tell is very good.

Imagine trying to watch The Lord of the Rings and every 15 minutes big red letters flash on the screen “IT’S ONLY A STORY!” Forget how annoying that would be from an entertainment perspective – how well do you think you’d be able to pick up the key themes? Do you think it would inspire you to incorporate its values of honor and integrity and courage in your life?

When you constantly put disclaimers on your beliefs, you undermine the positive effect those beliefs have on your life. You tell yourself “maybe it’s not true” and so when things get complicated – or just hard – you’re far more likely to stop acting in accordance with those beliefs. Disclaimers empty beliefs of their power.

In another part of her post, Yvonne says

I have always said that I don’t have a fixed belief (in the sense of assenting to a creed); instead, I have working hypotheses to explain my experiences.

If you’re running a scientific experiment, you understand that your hypothesis is unproven – it’s an educated guess about how something works. But while you’re running the experiment you behave as though your hypothesis is exactly correct. You go through the steps you’d go through if your ideas are right. You maintain an open mind and you check the results to see if they confirm or reject the hypothesis – or if the results are inconclusive. But you run your experiment confidently, not tentatively.

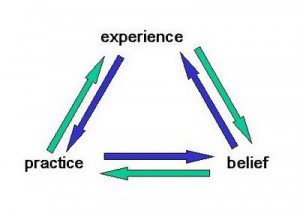

We have encounters with Gods and spirits and with the immensities of Nature. Things happen in our lives that are joyous and things happen that are traumatic. Some of these experiences are ordinary, some are ecstatic, some are transcendent. But they make an impact on us and so we interpret them – we assign meaning to them, based on our ideas about what’s important and how the world works. Eventually those interpretations become beliefs – working hypotheses to explain our experiences. We develop practices based on those beliefs, either to repeat the experiences or to incorporate their meaning into our lives.

This virtuous circle of experience, belief, and practice leads us into deeper relationships with the Gods and the virtues They embody, with Nature, and with each other. It helps us better understand ourselves, and thus prepares us for the work we are called to do in this world. We can enter the circle (or in this diagram, the triangle) at any point and move in either direction.

This virtuous circle of experience, belief, and practice leads us into deeper relationships with the Gods and the virtues They embody, with Nature, and with each other. It helps us better understand ourselves, and thus prepares us for the work we are called to do in this world. We can enter the circle (or in this diagram, the triangle) at any point and move in either direction.

But disclaimers weaken our commitment and limit our effectiveness.

Assume your beliefs are true. More importantly, act like they’re true – just don’t be an arrogant jerk about it. There is no certainty in religious matters, so respect the beliefs of others and hold your beliefs loosely. If you come to the conclusion they’re wrong or unhelpful, change them. But while you hold them, practice deeply.

In the end, judge your beliefs by the results they bring. Do they inspire you to live a deeper, more meaningful life? Do they inspire you to live in harmony with the Earth and all its creatures? Do they promote practices that help you deal with the hardships of life? Do they bring you into deeper relationships with the Gods – however you conceive of Them – and Their virtues? If so, your beliefs are good.

Remember that it’s OK to be wrong. Christian fundamentalists tell us that holding the “wrong” beliefs brings eternal damnation. Most Pagans have moved on from that long ago. Holding the “wrong” beliefs can also bring ridicule, as many of us know… some of us from both sides. But if we are going to move beyond the limitations of the dualistic mainstream culture we’re going to have to take some risks, including the risk of being wrong.

If you find a belief is demonstrably wrong, change it. If you find a belief leads you to act in ways that are unhelpful or not in accordance with your values, change it. Our mainstream culture places an inordinate emphasis on consistency, primarily for the juvenile pleasure of screaming “hypocrite!” at others and feeling superior about it. We can do better.

I agree with Yvonne Aburrow that “belief” is a word we need to reclaim and restore to its original meaning. I believe in the Gods because I value Them, I trust Them, and I support Their values and virtues. But until the general public understands that “I believe” means something more than “I think this might be true” I’m going to continue to describe my interpretations of my religious experiences firmly and confidently.

My Paganism has no disclaimers.