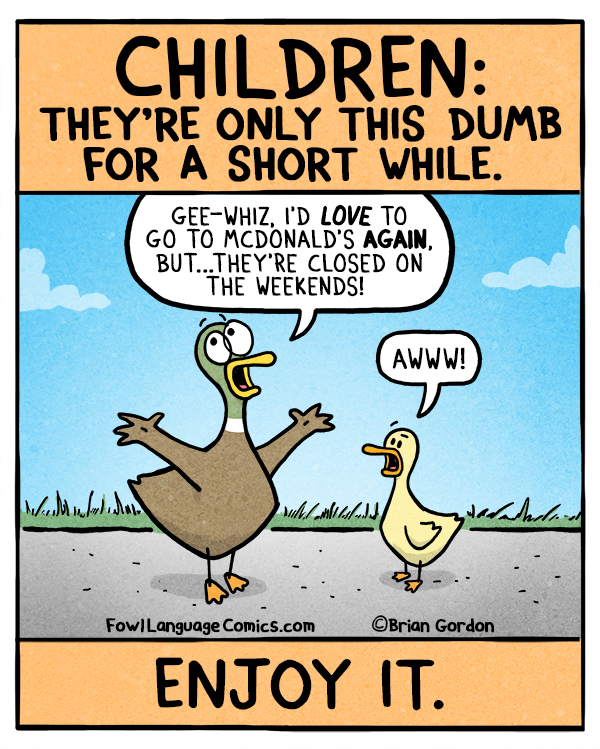

I recently saw the above cartoon shared on Facebook. Bizarrely, I saw it shared by progressives, and “liked” by progressives—and not just any progressives, progressive parents who embrace positive parenting. I was surprised and taken aback. Sharing cartoons that turn child abuse into a joke isn’t okay, and this isn’t okay either.

When did it become okay to joke about lying to children? Make no mistake, that is what this comic is talking about. What does it say about us, as a society, that we find a comic that makes light of and promotes lying to children funny? Do we really think that we as a society can joke about lying to children and then expect them to trust us? If we want a relationship of mutual trust and respect with our children, we need to prove ourselves worth of trust and respect.

And no, I’m some sort of non-parent who just doesn’t get it. I have two young children myself, and I understand the temptation to lie to them. Heck, I had the fight my urge to lie to my three-year-old earlier today! Our conversation went something like this:

“Can we go to the office and get candy?” Bobby asked.

“No honey, we’re not going to go to the apartment office right now.”

“Office closed?” Bobby wanted to know.

And that, right there, is where I could have said “yes.” He would have believed me, and that is where the conversation would have ended. I hesitated for a moment, knowing this. But I also knew that I want my son to trust me, and that he won’t trust me if I make a habit of lying to him for my own convenience.

“No, the office is open, but mommy’s working right now,” I told him.

“Oh,” he said. “Okay.”

And that was the end of the conversation, this time. Another day it might have gone on, with Bobby begging me to take him to the apartment office so that he could get a candy out of the bowl that sits on the apartment manager’s desk. I would have explained to him in more detail why I wasn’t going to take him to the office right then, or I might have realized that my reasons weren’t as sound as I thought—say, that “working” actually meant “Facebook,” and that a walk outside would be good for both of us. (I don’t see changing my mind as showing weakness, as some parents do.)

Of course, either of these outcomes would have required work on my part—more explaining, or a walk to the office–but they also would have offered payoff. Bobby would have gained more understanding of my need for time to work (and the fact that he can’t always have what he wants), or, if I’d changed my mind and taken him to the office, he would have learned that I listen to him and don’t refuse his requests arbitrarily or out of hand.

Lying to children too young to question what their parents say may seem convenient in the short term, but it’s nothing more than a shortcut around actual engagement and learning—and it’s a shortcut with some pretty severe potential negative consequences down the road. My daughter Sally is six now, and old enough to question what I tell her. She, too, likes going to the office and getting candy, and when she asks and I tell her its closed—because sometimes the office is closed—she is not always convinced (after all, I might be wrong) and likes to go and check.

When Sally checks for herself whether the apartment office is open, she does so in case I have it wrong, not because she thinks I might be lying. Office hours vary on the weekends, and weekday hours vary with the season, and as a result I haven’t always been correct. But Sally knows that if I have it wrong—if the office is actually open when I thought it was closed—it is a mistake, and not intentional deception.

Kids need to know that their parents (and the other adults around them) tell them the truth (at least, as far as they know it). How else are they supposed to trust them?

I am by no means perfect in this area, and am still learning myself. Some years back Jimmy Kimmel encouraged parents to hide their children’s Halloween candy and tell their kids they’d eaten it all, and then videotape the whole thing and send it to him. We tried this in our own home with Sally. Unlike the children in Jimmy Kimmel’s videos, Sally didn’t curl up and cry. She knew that it would be out of character for us to eat her Halloween candy, given our emphasis on respecting children’s personal possessions, so she refused to believe us, and, with some quick investigative fieldwork, exposed our lie. At the time, Sean and I found the entire thing hilarious, but now I find it regrettable. After all, it taught Sally that her parents were willing to lie to her face.

And frankly, in hindsight, the entire “joke” was just mean.

It’s true that children, and especially young children, are often very gullible, but that shouldn’t be an invitation to deceive them. Instead, it should be only more reason to be truthful and forthright with them. Children’s impressionability and ignorance of the world around them makes our responsibility to them, as adults, only greater.

There’s a lot more discussion, these days, about bullying in schools. I think we sometimes forget that adults, too, can also bully children, and, further, that parents can bully their own children. We would all be horrified if someone took a blind student’s books and held them just out of reach, taunting them. Why is it okay, in contrast, to take advantage of young children’s ignorance and gullibility?

I’ll give you a hint—it’s not. Let’s stop treating lying to children as a “joke.”