I’ve long been fascinated by the idea that evangelicalism has “borders” that it enforces—beliefs that are considered required for membership. Every religion or belief system has such borders, they just define and defend them differently. What I find fascinating about watching the borders evangelicals draw is how drastically these borders have changed over time, and how very specific they can get. Fred Clark of the Slacktivist uses the term “tribal gatekeepers” to describe this phenomenon.

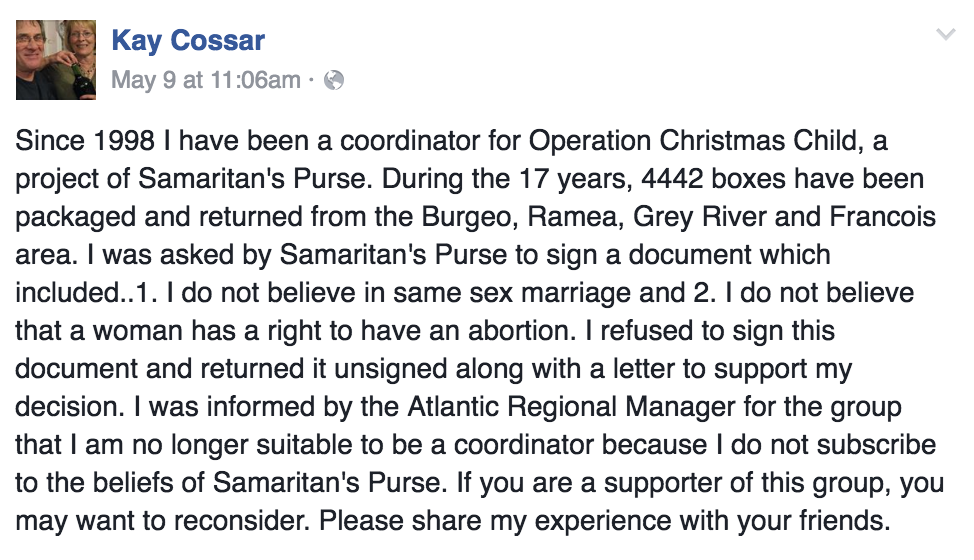

I was reminded of this concept by this Facebook post by Kay Cossar:

Text: “Since 1998 I have been a coordinator for Operation Christmas Child, a project of Samaritan’s Purse. During the 17 years, 4442 boxes have been packaged and returned from the Burgeo, Ramea, Grey River and Francois area. I was asked by Samaritan’s Purse to sign a document which included.. 1. I do not believe in same sex marriage and 2. I do not believe that a woman has a right to have an abortion. I refused to sign this document and returned it unsigned along with a letter to support my decision. I was informed by the Atlantic Regional Manager for the group that I am no longer suitable to be a coordinator because I do not subscribe to the beliefs of Samaritan’s Purse. If you are a supporter of this group, you may want to reconsider. Please share my experience with your friends.

Samaritan’s Purse is an evangelical ministry that provides aid in countries overseas. They offer disaster relief and medical aid, but are best known to many for their Operation Christmas Child, an increasingly controversial program that asks American evangelicals to fill shoeboxes with various practical goods and toys and take them to a local distribution center to be collected and sent to children in other countries. An increasing number of people are speaking up about the inefficiency of this process, the way it bypasses local economies, the mismatch in goods needed in specific cultures, and the use of promotional literature added to the shoeboxes to turn an opportunity for giving into something with strings attached. There’s a growing recognition that the real beneficiaries of the program are American evangelicals, who get to have good feelings about helping poor benighted children in other countries.

But let’s leave all of this aside and look at Samaritan’s Purse’s statement of faith:

Samaritan’s Purse bases its ministry on the following statement of faith:

• We believe the Bible to be the inspired, the only infallible, authoritative Word of God. 1 Thessalonians 2:13; 2 Timothy 3:15-17.

• We believe that there is one God, eternally existent in three persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Matthew 28:19; John 10:30; Ephesians 4:4-6.

• We believe in the deity of our Lord Jesus Christ, in His virgin birth, in His sinless life, in His miracles, in His vicarious and atoning death through His shed blood, in His bodily resurrection, in His ascension to the right hand of the Father, and in His personal return in power and glory. Matthew 1:23; John 1:1-4 and 1:29; Acts 1:11 and 2:22-24; Romans 8:34; 1 Corinthians 15:3-4; 2 Corinthians 5:21; Philippians 2:5-11; Hebrews 1:1-4 and 4:15.

• We believe that all men everywhere are lost and face the judgment of God, that Jesus Christ is the only way of salvation, and that for the salvation of lost and sinful man, repentance of sin and faith in Jesus Christ results in regeneration by the Holy Spirit. Luke 24:46-47; John 14:6; Acts 4:12; Romans 3:23; 2 Corinthians 5:10-11; Ephesians 1:7 and 2:8-9; Titus 3:4-7.

• We believe in the present ministry of the Holy Spirit, whose indwelling enables the Christian to live a godly life. John 3:5-8; Acts 1:8 and 4:31; Romans 8:9; 1 Corinthians 2:14; Galatians 5:16-18; Ephesians 6:12; Colossians 2:6-10.

• We believe in the resurrection of both the saved and the lost; the saved unto the resurrection of eternal life and the lost unto the resurrection of damnation and eternal punishment. 1 Corinthians 15:51-57; Revelation 20:11-15.

• We believe in the spiritual unity of believers in our Lord Jesus Christ and that all true believers are members of His body, the Church. 1 Corinthians 12:12, 27; Ephesians 1:22-23.

• We believe that the ministry of evangelism and discipleship is a responsibility of all followers of Jesus Christ. Matthew 28:18-20; Acts 1:8; Romans 10:9-15; 1 Peter 3:15.

• We believe God’s plan for human sexuality is to be expressed only within the context of marriage, that God created man and woman as unique biological persons made to complete each other. God instituted monogamous marriage between male and female as the foundation of the family and the basic structure of human society. For this reason, we believe that marriage is exclusively the union of one genetic male and one genetic female. Genesis 2:24; Matthew 19:5-6; Mark 10:6-9; Romans 1:26-27; 1 Corinthians 6:9.

• We believe that we must dedicate ourselves to prayer, to the service of our Lord, to His authority over our lives, and to the ministry of evangelism. Matthew 9:35-38; 22:37-39, and 28:18-20; Acts 1:8; Romans 10:9-15 and 12:20-21; Galatians 6:10; Colossians 2:6-10; 1 Peter 3:15.

• We believe that human life is sacred from conception to its natural end; and that we must have concern for the physical and spiritual needs of our fellow men. Psalm 139:13; Isaiah 49:1; Jeremiah 1:5; Matthew 22:37-39; Romans 12:20-21; Galatians 6:10.

You know what’s interesting? There’s nothing in here about the rapture or the tribulation, there’s nothing in here about Calvinism or Arminianism, and there’s nothing in here about evolution. In other words, some of the greatest points of disagreement among American Protestants of the 19th and early 20th centuries are simply not mentioned. The immediate focus on the Bible as inspired and infallible is in line with the early twentieth century roots of modern evangelicalism, but the fierce battle over whether fundamentalists should remain in apostate denominations as salt and light or come out of such denominations and be separate—a battle that waged fiercely in the 1930s and 1940s—is absent from this statement.

One might think that a statement of faith would be timeless and unchanging—especially for a group which claims to rely so fully on an infallible and inspired Bible—but evangelical statements of faith tend to change over time as the borders of evangelicalism change. Because that’s what these statements of faith are for—policing borders, determining who is in and who is out. Can you be an evangelical and support marriage equality? Can you be an evangelical and support women’s right to choose? Can you be an evangelical and believe in gender equality? Can you be an evangelical and believe in evolution? Where do these borders lay?

I ran into these borders myself when I was in college. It was there I became a theistic evolutionist. When my parents found out, they looked at me with a level of sheer disappointment that would crush any child’s heart. It was clear—very clear—that they believed my salvation was one the line, and also that I was no longer in their tribe, no longer a part of their self-conceived group. I had transgressed the borders of belonging they had drawn around their faith, their interpretation of evangelicalism, their idea of what an evangelical is. I didn’t know then, but known now, that there was a century-long precedent for this. When evangelicals’ fundamentalist ancestors of the 1920s waged battle over evolution, they made their lines clear—and these, at the time, were brand new lines that had not been drawn before.

In that light, it is interesting that Samaritan’s Purse does not mention the age of the earth in their statement of faith. They would, presumably, be okay with a theistic evolutionist working for them provided that person is against marriage equality and anti-abortion. The boundaries they draw differ slightly from those drawn by my parents, from those drawn by 1920s fundamentalists, and from those drawn by seminaries that require an affirmation of complementation gender relations (i.e., a rejection of gender equality). Each specific evangelical ministry, college, or magazine draws its lines slightly differently, each choosing its own particulars.

These extremely specific statements of faith are not preordained. After all, the word evangelical has its roots in words like “evangelize” or “evangelism.” Evangelicalism ostensibly centers on the understanding that we are sinners condemned to hell for our wrongdoing, that through Christ and his sacrifice on the cross we can find salvation and freedom and access to heaven, and that Christians must spread this “good news” to those not yet reached through personal evangelism and missions. Historically, this is what the term “evangelical” has meant. It is only in the twentieth century that evangelicals have sought to draw closer lines, no longer feeling that sharing this basic understanding is sufficient to make one an evangelical. Those lines have shifted and changed over the course of the twentieth century, but have always been there—and, interestingly, have always been contested.

Let’s step away from this history and turn back to Samaritan’s Purse, because there’s one more thing to be said. Check out their about section:

The story of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:30-37) gives a clear picture of God’s desire for us to help those in desperate need wherever we find them. After describing how the Samaritan rescued a hurting man whom others had passed by, Jesus told His hearers, “Go and do likewise.” For over 40 years, Samaritan’s Purse has done our utmost to follow Christ’s command by going to the aid of the world’s poor, sick, and suffering. We are an effective means of reaching hurting people in countries around the world with food, medicine, and other assistance in the Name of Jesus Christ. This, in turn, earns us a hearing for the Gospel, the Good News of eternal life through Jesus Christ.

Can I just say that this is a precisely backwards interpretation of this parable? In the story, the Samaritan, and not the Jewish religious leaders of the day, is the one who stops to help an injured traveler, putting him up in an inn with his own money. What was a Samaritan? The Samaritans were considered heretics by the Jews. They had transgressed the Jews’ borders of belonging and were outside of them. Partly it was their ancestry that was at issue, but their theology was distinct and different enough to be a problem as well. Additionally, the Samaritan did not take the opportunity to preach to the man he rescued. Indeed, he did not in any way approach his service to this injured traveler as an opportunity to evangelicalism.

It is highly ironic that a ministry named Samaritan’s Purse would create theological borders intended to keep today’s Samaritans—i.e. anyone evangelicals consider heretical—out of their organization.