We’re returning to our occasional series of posts on work and vocation (linked at the bottom of this post) in Christian history by Faith and Work Channel senior editor and Christian History magazine senior editor Chris Armstrong. Enjoy!

The Reformed tradition

Calvin elaborated on the Lutheran doctrine of vocation, freeing people to pursue the vocations of their choosing rather than to remain in a single “social standing” as the more conservative Luther had counseled. The Calvinist Puritans developed the idea of the sacred importance of economic work in ways that prepared the ground for the flourishing of capitalism: as Weber argued, obedience, diligence, delayed gratification, and other “ascetic” virtues were transferred in Puritanism into the world of work, and resulted in the creation of tremendous wealth.

Puritans often condemned the pursuit of money and goods for their own sake. Their “work ethic” was never about money-making. But “it opened the way to a career in business, especially for the most devout and ethically rigorous people.” Leland Ryken describes the Puritan idea of calling as including “the providence of God in arranging human tasks, work as the response of a steward to God, contentment with one’s tasks, and loyalty to one’s vocation.”

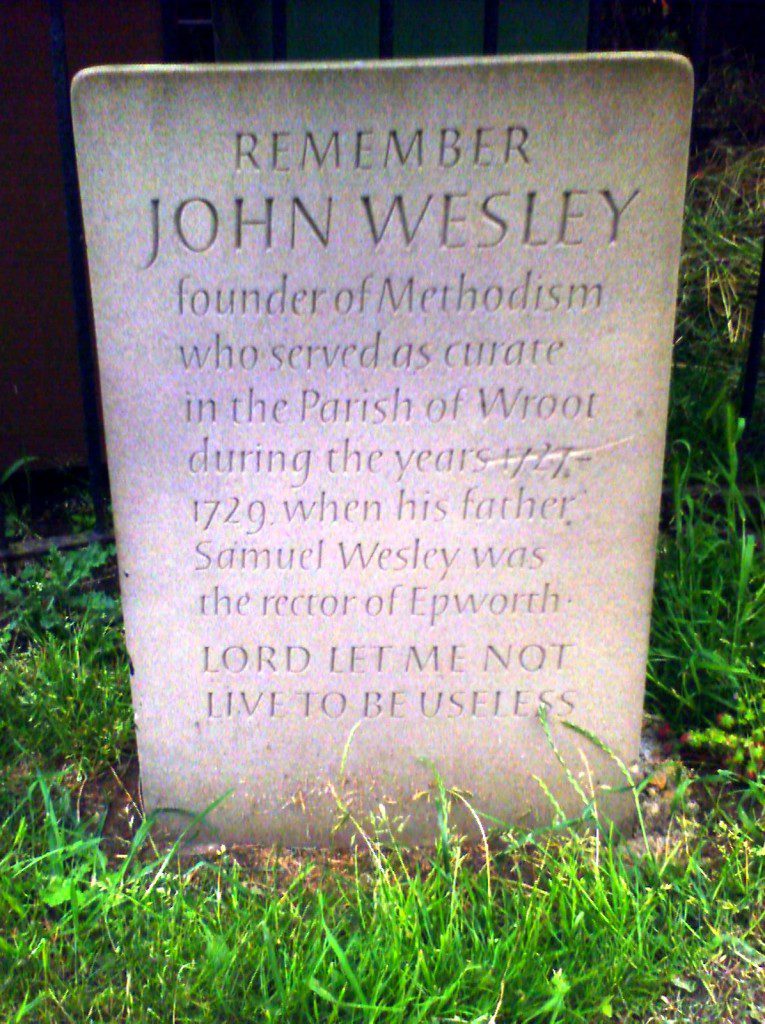

Wesley and the industrial revolution

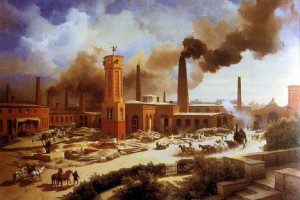

The next great change in Christian attitudes to economic work came with the industrial revolution, which was already ramping up in the time of the great 18th-century preacher John Wesley, when the commercial virtues of the Puritans and the new capitalist habits of long-term investment began to create the industries and factories that would drive Western economic growth in the centuries to come.

The Industrial Revolution brought with it the aggregation of work into factories, removing it from the town-based communal settings of homes and shops and catapulting it into the large-scale settings of cities, whose rapid growth resulted, especially in the century after Wesley, in terrible social problems. Like a great landslide, the revolution swept away centuries of solid economic and social ground, leaving Europe and America battered and bewildered. Old skills were quickly devalued, thousands abandoned the towns and countryside for the cities. The evident gap between rich and poor in some urban areas—and even between middle-class and working-class—wounded Christian consciences.

Christian responses varied, of course—from the Holiness preaching, “blood-washed” singing, and homes for fallen women of the Salvation Army; to the clean, safe, and new model villages built for workers by the Quaker owners of the Cadbury and Rowntree cocoa companies; to the fight for an alcohol-free world of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union; to attempts by Social Gospel advocates to bring in a new society by working for the “salvation” not only of individuals but of corporate and social entities. And many who might never have darkened the door of a traditional Christian church—from members of communal societies to labor unionists—sought and claimed the directing example of Jesus as they grappled with how to right a world turned upside down.

In those days the church was awakening to its need to understand the fundamental nature of enterprise and economics, and to meet new, modern conditions with new ways of promoting human flourishing. They searched Scripture for light on economic wisdom, on human dignity rooted in the image of God, on the value of all legitimate work, on the call to love one’s neighbor as oneself, and on the fundamental importance of social institutions. And in these areas as in so many others, Wesley grappled and thought and taught.

His Methodist movement, which always kept at the center of its focus the poor—settled and working as well as indigent and destitute—insisted that Methodists educate themselves – that they improve their minds learn new skills as well as a new and sanctified way of living in the world.

Originally published at Grateful to the Dead.

Previous posts in this series:

- Getting the beginning and end of the story right

- We were made to work

- Jesus the incarnate worker God’

- A brass-tacks, real-world theology of work and vocation

- Early Christianity and everyday work

- The contemplative contribution

- Luther on ordinary work and vocation

Image: José Luís Agapito, “Industrial Revolution.”