I find it very odd when Pagans and atheists hold forth on the subject of a book they probably haven’t read. Quite often their perspective on it seems to be informed by evangelical or fundamentalist interpretations of the book, and they seem blissfully unaware that – whilst certain bits of the book, taken out of context by right-wing Christians, have been used to justify the perpetuation of slavery, the persecution of LGBT people, and all sorts of other horrors – there is much more to the Bible than the wilful and selective misinterpretation of it by right-wing Christians would suggest.

Recently, Jason Mankey posted a piece on why it is a good thing that Pagans don’t have a holy book. I quite agree that having a single holy book (especially one which is taken to be the literal word of God) is a very bad thing – but I can think of a number of people who are starting to regard “the” Book of Shadows as a holy book, thinking that you have to do the rituals in the way they are written, and that the theology implied in the rituals is definitive and normative. To many Pagans, all books are holy, not just one. Jason quite correctly critiques how right-wing Christians regard the Bible as inerrant and take it out of context – but there are plenty of Christians who don’t regard it as inerrant and spend ages researching the context in which the books of the Bible were written, sometimes to the point of being complete and utter nerds about it. Full credit to Jason for acknowledging the complexity and long development of the books of the Bible, but the reason we know all that stuff is mostly because liberal Christians went and did the research. He also interprets the word “prophet” as someone who is regarded as infallible. I would say that a prophet is anyone who speaks truth to power, and criticises the status quo. Like Amos and Micah.

Even more recently, Katrina Rasbold posted a piece refuting the ridiculous idea that Christians shouldn’t address God as Mother. But her interpretation of the Bible as absolutely riddled with patriarchy and misogyny is more than a little off. I agree that the New Testament is pretty patriarchal at times (all that stuff about the man being the head of the woman just as Christ is head of the Church) but there is also some pretty radical stuff about men and women, slave and freeman, Jew and Gentile, all being one in Christ.

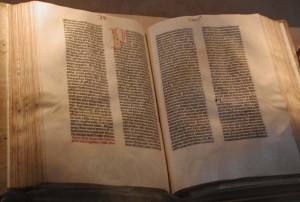

One thing that ex-Christians often do is to continue the perspective that they were taught in the tradition they left. If the tradition that they left viewed the Bible as the inerrant word of God, and a single unified text, then they regard it as a completely erroneous single unified text. But the idea that the Bible is the inerrant word of God has been challenged and modified many times. The Orthodox Church has acknowledged since the 4th century that the creation story in Genesis is a metaphor. The Higher Criticism in the 19th century demonstrated the multiple authorship of the Bible, especially the first five books, which were traditionally attributed to Moses. The Higher Criticism is now largely forgotten, but modern fundamentalism was formulated in response to it, and at the time it was held to be a bigger threat to fundamentalist Christianity than the theory of evolution.

But modern Biblical criticism has shown that the Bible is a palimpsest of many different texts, coming from many different perspectives. Even texts that were written down at the same time have been shown to be the work of multiple authors, whose ideas were very different from each other. So any time we read the books in the Bible, we should bear in mind that it is the result of a tug of war between multiple perspectives. For example, the book of Genesis appears to have been compiled from the works of two different authors, known as the J author and the E author. They are called that because J uses the name Yahweh for God, and E uses the name El, or Elohim. Not only are their names for God different, but their theological perspectives are different. That’s why there are two creation stories in Genesis: one is J’s version, the other is E’s version. Similarly, David Doel (a Jungian analyst and Unitarian minister), in his book, That Glorious Liberty, has suggested that there were not one but two Pauls – the liberal one who wrote all the expansive mystical stuff in Corinthians, and a later imitator who wrote the less liberal stuff in some of the other writings attributed to Paul. Let’s face it, if you wanted your work accepted, the idea of attributing it to a much-admired leader was a very smart move. And some of the stuff that “nice Paul” says and does – like writing to the female leaders of various early churches – is very inconsistent with some of the more patriarchal stuff attributed to him. A Christian blogger, John Walker, even argues that the text about women not speaking in church has been mistranslated and misinterpreted.

I strongly recommend reading The Bible: The Biography by Karen Armstrong, which goes into just the right level of detail about the history and development of the books that we now refer to as the Bible. It should be remembered that “Bible” means library, and that it is a collection of books, not a single book.

If you read the Tanakh (the collection of books referred to by Christians as “The Old Testament”) as a sequence of evolving ideas about the divine, you can see that belief about the nature of God changes from the beginning to the end (remember that the books were written over several hundred years, and that they developed from oral traditions), and the emphasis on what is believed to please God also changes. At the beginning, Yahweh is seen as one god among many, with whom the Jewish people have a special relationship. Then he becomes seen as the supreme God, the Creator. Towards the end, he is seen as the only God. At the beginning, the way to please Yahweh was to offer him sacrifices; towards the end, it becomes more about people treating each other decently, and taking care of the poor (this is particularly noticeable in the books of Amos and Micah).

In between we have the Book of Job – an extended meditation on life’s unfairness, and how God can be a bit of a git sometimes; Ecclesiastes – a wistful little meditation on life’s ups and downs; the magnificent poetry of the Psalms; and the beautiful erotic poetry in The Song of Solomon (can’t see any misogyny in that text, no sirree). There are also the marvellous stories of David and Jonathan, and Ruth and Naomi.

The Bible has inspired people to rise up against their oppressors and demand freedom and equality. It is full of rich stories and poetry and demands for equality. It has a lot of stories of strong female heroines. It is much more than a single book – it is a collection of stories. Therefore, we should stop reading it as a religious text, and read it as a classic work of our shared culture – the way we read Shakespeare or Milton.

I think it is also important to pay attention to Jewish interpretations of the text, not just swallow hook, line, and sinker the interpretations placed on it by Christians – for example, the Servant Song in Isaiah is not a prophecy of Christ, it’s a song about a particularly social-justice-loving king who was a contemporary of Isaiah.

And don’t forget that when the Bible was made available for people to read in their own language, it caused a massive shift in authority from the priesthood to the laity, who were now able to read and interpret the text for themselves. Sometimes their interpretations were really bad, but sometimes they were really good – it rather depended on their prior inclinations. But at least the book was now freed from the clutches of the Church, and available to the laity to read. The Jews, of course, have always had the freedom to read and interpret the Tanakh for themselves – and they really enjoy discussing the many different possible interpretations – but let’s not forget what it meant for people finally to be able to read and interpret the Bible for themselves.

The best bits of the Bible from a Pagan point of view

The creation story is really interesting, because what happened was that the monotheistic Hebrews basically cobbled together elements of creation stories from the cultures around them, and put a monotheistic spin on them, replacing any mention of other gods with Yahweh. In Eden: The Buried Treasure (2009), the author, Eve Wood-Langford, shows the sources of all these stories in earlier pagan texts from Mesopotamia, including the Epic of Gilgamesh. For instance, the story of the Flood was originally a story about Ishtar flooding the world because she lost her temper.

The gods were angry at mankind so they sent a flood to destroy him. The god Ea, warned Utnapishtim and instructed him to build an enormous boat to save himself, his family, and “the seed of all living things.” He does so, and the gods brought rain which caused the water to rise for many days. When the rains subsided, the boat landed on a mountain, and Utnapishtim set loose first a dove, then a swallow, and finally a raven, which found land. The god[dess] Ishtar, created the rainbow and placed it in the sky, as a reminder to the gods and a pledge to [hu]mankind that there would be no more floods. See the text Epic of Gilgamesh: Sumerian Flood Myth.

Numerous other creation stories from the Middle East have a creator god, Marduk, making the Earth from the dismembered remains of a great serpent, Tiamat. In Sumerian mythology, Tiamat was the salt water, and her consort Apsu was the sweet water. In the book of Genesis, it says that the spirit of God divided the waters.

The story of Esther looks like another interesting retelling of a pagan myth. Esther and her uncle Mordecai completely overcome a plot by Haman to kill all the Jews in Persia. It may be a coincidence, and I can’t find a pagan Sumerian story that mirrors the details of the Esther story, but the names Esther and Mordecai are very similar to Ishtar and Marduk. The story is celebrated in the festival of Purim, and Esther is the main protagonist of the story.

Esther is not the only strong feisty woman in the Tanakh – there are also Deborah, Naomi, Ruth, and Jael. Deborah was the only female judge mentioned in the Bible, and led a successful counterattack against the forces of Jabin king of Canaan and his military commander Sisera. In the same book, you can read the story of Jael, who spiked the enemy general in the head with a tent-peg. Hardly an image of the submissive and quiet type!

Then there’s Ruth and Naomi, who, even if they were not lesbians in the modern sense, were two women who loved each other so much that Ruth was prepared to follow Naomi into possible slavery in order to stay with her. This story is very inspiring for Christian lesbians, and Ruth’s vow is used in wedding ceremonies in the Anglican Church, and in same-sex weddings in liberal churches too.

“Don’t urge me to leave you or to turn back from you. Where you go I will go, and where you stay I will stay. Your people will be my people and your God my God. Where you die I will die, and there I will be buried. May the God deal with me, be it ever so severely, if even death separates you and me.” (Ruth 1:16-17)

And of course, David and Jonathan, who clearly loved each other very much.

“When David had finished speaking to Saul, the soul of Jonathan was bound to the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul. Saul took him that day and would not let him return to his father’s house. Then Jonathan made a covenant with David, because he loved him as his own soul. Jonathan stripped himself of the robe that he was wearing, and gave it to David, and his armor, and even his sword and his bow and his belt.” (1 Samuel 18:1-4)

And then there’s the marvellous extended love poem that is the Song of Songs / Song of Solomon, dripping with eroticism. As Wikipedia points out:

Scripturally, the Song of Songs is unique in that it makes no reference to “Law”, “Covenant” or to Yahweh, the God of Israel, nor does it teach or explore “wisdom” in the manner of Proverbs or Ecclesiastes (although it does have some affinities to Wisdom literature, as the ascription to Solomon suggests). Instead, it celebrates sexual love. It gives “the voices of two lovers, praising each other, yearning for each other, proffering invitations to enjoy”. The two are in harmony, each desiring the other and rejoicing in sexual intimacy; the women (or “daughters”) of Jerusalem form a chorus to the lovers, functioning as an audience whose participation in the lovers’ erotic encounters facilitates the participation of the reader.

And the philosophical perspective of Ecclesiastes (Koheleth in Hebrew) is strikingly similar to that of contemporary Paganism – it’s all about cyclicity: the cycles of life, death, and rebirth.

There is a time for everything,

and a season for every activity under the heavens:

a time to be born and a time to die,

a time to plant and a time to uproot,

a time to kill and a time to heal,

a time to tear down and a time to build,

a time to weep and a time to laugh,

a time to mourn and a time to dance,

a time to scatter stones and a time to gather them,

a time to embrace and a time to refrain from embracing,

a time to search and a time to give up,

a time to keep and a time to throw away,

a time to tear and a time to mend,

a time to be silent and a time to speak,

a time to love and a time to hate,

a time for war and a time for peace.

I also think that Amos and Micah deserve special mention for advocating people being nice to each other for a change, instead of focusing on sacrifices, ceremonies, and the outward forms of religion.

“I hate, I despise your feasts,

and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies.

Even though you offer me your burnt offerings and grain offerings,

I will not accept them;

and the peace offerings of your fattened animals,

I will not look upon them.

Take away from me the noise of your songs;

to the melody of your harps I will not listen.

But let justice roll down like waters,

and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream. (Amos 5: 21-24)

Amos spoke against the growing gap between the very rich and the very poor. His main themes of social justice, God’s omnipotence, and divine judgment became the basis of prophecy. Micah was a contemporary of Amos and said that the beautification of Jerusalem was financed by dishonest business practices, which impoverished the city’s citizens; he also emphasised social justice, and complained about houses being seized and sold by the oppressors (Micah 2). He emphasised that:

“what does the Lord require of you

but to do justice, and to love kindness,

and to walk humbly with your God?” (Micah 6:8)

Both of these prophets have been inspirational for Unitarians, Universalists, Unitarian Universalists, and Quakers, who are widely acknowledged to be pretty hot on social justice issues.

Then there are all the times when the apostle Paul quotes from pagan poets like Epimenedes and Aratus. That quote about “in whom we live, move and have our being” is from a pagan poet. Paul also quoted from a number of other classical pagan poets.

So, the next time you decide to do a little Pagan criticism of the Bible – at least read some of it first. And don’t assume that just because one bit of the Bible has something dodgy in it, that means all the rest of it is worthless. It is a library of different books by different authors, written at different times. Since we don’t take it literally (along with thousands, perhaps millions, of progressive and liberal Christians), we are free to enjoy it as literature. And it is – like any collection of literary texts – extraordinarily rich in meaning and symbolism.

You might be wondering why I care… well, I happen to like the Tanakh and think it is a fascinating record of a people’s relationship with their deity over centuries. I also think that a book that inspired Martin Luther King and Desmond Tutu, among many others, can’t be all bad. And I like the poetry and the stories in the book, and think that they are part of our culture, whether we like it or not, and that we should reclaim them from fundamentalists and appreciate them for what they are. There are even bits of the New Testament that I quite like, mainly the Sermon on the Mount – but I have to say I prefer Tolkien and Shakespeare and Chaucer.

Another reason why it matters is that every time you assert that the Bible is a book full of patriarchy, misogyny, justifications for slaughter, and condemnation of gay people, you are damaging the cause of progressive Christians and liberal Jews, by denying the validity of their liberal interpretations of the Bible. These people are on the same side as us: they want same-sex marriage, religious tolerance, and equality for women.

Some of my previous blogposts about the Bible:

- An interesting conversation – 14 February 2013

- The woman caught in adultery – 21 February 2012

- Same-sex love in the Bible – 31 December 2011

- Airbrushing the Bible – 28 July 2011

- Biblical phrases in common usage – 10 July 2011

- William Tyndale – 10 July 2011

- Status of religious texts – 15 September 2010

- The Bible: take it or leave it? – 17 April 2010

- Naomi and Ruth in art – 2 July 2009

- Reviews of the Bible on Amazon – 5 May 2009

A random sample of progressive Christians talking about gender:

- Let’s change the Lord’s Prayer (again) – calling for a change in the Lord’s Prayer to include Mother Earth – Roger Wolsey

- A Transgender God: Adam Ericksen

Progressive Christians talking about the Bible:

- Does the Bible matter? Progressive Christians and Scripture – Marcus Borg

- 16 ways Progressive Christians interpret the Bible – Roger Wolsey

- How to read the Bible: A Progressive Christian Guide – Jim Burklo

And this is a poem I wrote about the Bible in 2009:

Craggy old book

Craggy old Bible

Wisdom, treasure, bitter delight

Poison and perfume

Tales of abduction

Rape and seduction, sorrow

and exile. Selah.

Darkness and light dance

on the face of the waters

calling my name.

Across the abyss

the words are inaudible

speaking mystery.

Pageant of prophets

madmen and sages, voices

cry in the desert.

not universal,

absurdly particular:

seventy faces.

opaque parables

they insinuate themselves

into your heart.

myriad stories

speak of relationship:

a god and a people

will they, won’t they love?

making up and breaking up

Yahweh and Israel

stormy lovers dance

through the deserts of Canaa:

prophets foretell doom

a star blazing forth

over the land: carpenter

reshapes his world

then in a garden

a man was betrayed

rejected cornerstone

locked in a kiss

for all time, Jesus, Judas

lover, beloved

a garbled message

spreading pentecostal fire

a new betrayal

words overwritten –

he said “love one another”

not “worship me”