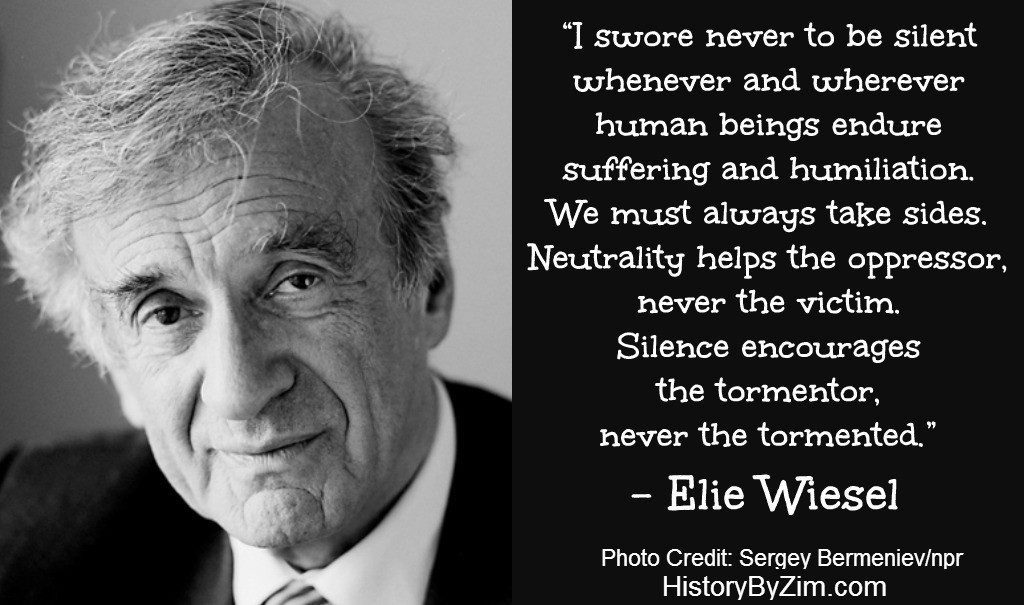

When Elie Wiesel died recently, millions paid tribute to the moral witness of his life and work by posting memes on social media, often featuring quotes like this one:

That’s an inspiring statement, but I do not know quite how to be inspired by it — I do not know what it is that it should inspire me to do or to advocate that others do on my behalf.

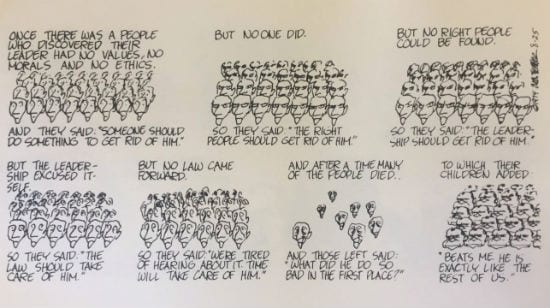

I don’t think I’m alone in this. No one else seems to know what to do either. And so, because we do not know what to do, we usually wind up doing one of two things: nothing, or dropping a lot of bombs. Neither of those seems like either a good or an effective approach.

When we see “human beings endure suffering and humiliation” — or, more acutely, when we see human beings slaughtered en masse — we want to take sides against that slaughter and suffering. We want to say, as Wiesel powerfully taught us, “Never again.”

That is a powerful argument for intervention. And, let’s be clear, Wiesel was a powerful proponent of intervention — of military intervention. (That’s why it was so strange, on the occasion of his death, to see so many people who seem otherwise opposed to military intervention praising Wiesel by sharing quotes like the one above.)

The moral logic of that quote, of that “Never again” argument for military intervention, is compelling. Even a Canadian pacifist like Bruce Cockburn could understand it, singing “If I Had a Rocket Launcher …”

As I wrote here earlier this year, I think that logic was also what drove the Obama administration’s decision to intervene in the Libyan civil war, enforcing a no-fly zone against Gaddhafi’s military. That decision, I think, was shaped by two prior experiences from the 1990s — the absence of any credible international intervention to stop the Rwandan genocide, and the contrasting effectiveness of the NATO-led bombing that helped end the siege and slaughter in Bosnia. The former stood as an example of exactly the shameful “neutrality” that Wiesel warned against, while the latter offered the misleading hope that it could be replicated as a formula for future success — bomb the Bad Guys until they’re forced to accept some settlement.

Again, I’m not arguing that this decision was right, or that this reasoning is beyond criticism. I’m just pointing out that this was, apparently, the reasoning that drove that decision.

I do, in fact, want to disagree with that decision and to criticize that reasoning. I want to say that Bosnia seems to have been an exceptional case and therefore a poor model — that more often than not, this dropping of “freedom bombs” just seems to escalate an unending cycle of violence and slaughter. “She swallowed the cat to catch the bird, she swallowed the bird to catch the spider, she swallowed the spider to catch the fly …”

But to make that criticism, I need to be better able to articulate an alternative course of action.

I don’t mean that every criticism needs to be supported by a viable, flawless alternative. It is perfectly valid and legitimate to respond to some bad ideas by simply stating, “No. Don’t do that.” But in the case of mass-slaughter — of “human beings enduring suffering and humiliation,” torment, oppression and death on an incomprehensible scale — I need to be able to say more than that.

And I don’t know how to say that, or what to say.

I’ve been looking for help with that — eagerly scouring articles lambasting Obama and Hillary Clinton for their decision to intervene in Libya, hoping to find some indication of what they ought to have done instead. But mostly, what I’ve found is either the suggestion that they should not have done anything, or the suggestion that they should have bombed Libya even harder.

See, for example, this TED Talk from former CIA operative Evan McMullin, which I saw today due to McMullin’s potential independent bid for president as a conservative alternative to Donald Trump.

The first half of McMullin’s talk is a powerful, moving description of the slaughter and atrocities committed by the Assad regime in Syria (content note: this includes graphic, horrifying photographs of the dead). McMullin is right and righteous in his determination that such horrors are intolerable and that they demand some response.

But as he pivots to the second half of his speech, we realize that he hasn’t got any more specific suggestions for what that response might be, other than more bombing. He cites the NATO intervention in Bosnia as his model, arguing that “the most critical obstacle to stopping atrocities” is “government’s lack of political will to do it.” Green Lanternism to unleash the bombs.

What McMullin sees there as a “lack of political will” is, rather, a function of the recognition that more bombs is rarely an effective response and that it sometimes makes things even worse. What he perceives as a lack of will may, in fact, be a desperate search for something more effective and less potentially destructive than the one crude response we already know about. I don’t think that a greater willingness to drop bombs is the answer. But, again, I don’t know what a better answer looks like.

So if you have encountered, or imagined, some other, better option, I would very much like to hear it and to learn from it, and to share that learning with others.

One thing about this I think I have come to understand is that it’s misleading and distorting to view these situations only in the shortened time-frame in which they’re at the point of crisis — only at the point at which Gaddhafi stands poised to decimate the popular uprising with his air force. That limited time frame limits our options and our imagination. Once the Chinese army has overrun the Korean city of Hungnam and hundreds of thousands of civilians are massed at the port, awaiting either rescue or slaughter, then few options remain other than shelling that army to facilitate the rescue. That’s military intervention as a last resort, which ought to come after all the earlier possibilities have been resorted to and have failed, not because we sat idly awaiting the crisis that would allow us to pursue such a last resort as our first and only form of action.

What I want to think about, then, is not just how to intervene at the moment of crisis, but how to intervene before then — in ways that do not involve the dropping of bombs — so as to prevent that moment of crisis from arising. Rather than only asking what should be done to stop Gaddhafi from using his air force to slaughter thousands, in other words, we should also be asking questions about how a guy like Gaddhafi was able to buy an air force in the first place.

And to think about all of that more clearly, I think it’s also important to clarify who “we” are.

“We have to take sides,” Wiesel taught us. But the vague, undifferentiated, all-encompassing fuzziness of that “we” limits what “we” are able to understand that as meaning. “We” becomes — exclusively — an antecedent for nations possessing large militaries and large arsenals. And if that is all that “we” means, then “taking sides” is going to mean nothing more than employing those militaries and arsenals. It’s going to mean dropping bombs, and only that.

I don’t think that is all that Wiesel meant to say, but unless “we” differentiate all the other possible meanings of “we,” then that is all “we” will be able to hear.